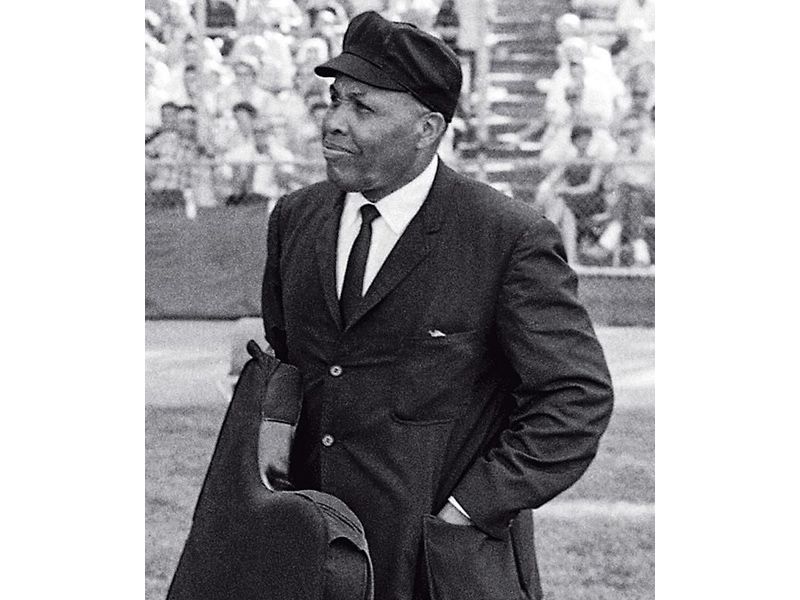

What Made Emmett Ashford, Major League Baseball’s First Black Umpire, an American Hero

During his 20-year professional career, his boisterous style endeared him to fans but rankled traditionalists

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/10/3e/103ec511-33e1-4ec6-a6b0-2b880bf2e35a/may2020_b35_prologue.jpg)

As the first black umpire in Major League Baseball, Emmett Ashford encountered plenty of hostility. The pitcher Jim Bouton documented Ashford’s difficulties in Ball Four, his revelatory diary of the 1969 season: “Other umpires talk behind his back. Sometimes they’ll let him run out on the field himself and the other three who are holding back in the dugout will snigger....It must be terrible for Ashford. When you’re an umpire and travel around the big leagues in a group of four and three of them are white...well, it can make for a very lonely summer.”

Ashford’s position was indeed a lonely one. Throughout his 20 years umpiring in the minor and major leagues, he was almost always the only black umpire on the field, and was sometimes subjected to racial epithets. But Ashford weathered these with grace. Today, the Spalding face mask he wore behind the plate is a tangible reminder of the courageous men and women who integrated U.S. sports after World War II. Still, only ten African-Americans have followed directly in Ashford’s footsteps, and it wasn’t until this past February that Major League Baseball hired its first black umpire crew chief, Kerwin Danley.

Ashford’s entry into umpiring was largely accidental. Born and raised in Los Angeles, he was on the track and baseball teams in high school. As a young man, he was good enough to play semi-pro baseball but usually rode the bench on weekends when better talent was available. For one game in 1941, the story goes, the scheduled umpire didn’t show up, and Ashford was asked to fill in. He did—“kicking and screaming,” he later said. One game led to another, and he soon established himself as a better umpire than ballplayer. “I gave them a little showmanship and the crowd loved it,” he later recalled of his flamboyant way of calling balls and strikes. .

Throughout the 1940s, Ashford honed his craft calling college and high-school games. Fans were dazzled by the way the diminutive but solidly built Ashford sprinted down the foul lines and by his exuberant style of calling balls and strikes (which one sportswriter likened to a “French prosecutor shouting ‘J’accuse’”).

A stint in the Navy during World War II interrupted his umpiring career, but something momentous happened just months before he was discharged, in 1946, to make his dream of reaching the Majors seem less remote: Jackie Robinson signed a minor-league contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers on his way to becoming the first black player in the Majors.

Ashford broke the color barrier for pro umpires in the low-level Southwest International League in 1951. For the next two years, he paid his dues, weathering abuse from racist fans in El Paso who berated him for doing a “white man’s job” and from a fellow umpire who called him “boy” until the usually calm Ashford had to threaten him physically. Ashford’s lifestyle and pay improved dramatically when he was promoted to the Pacific Coast League, then the Cadillac of the minor leagues, where he spent 12 seasons—until he moved up to the American League in 1966.

Over the next five seasons, Ashford became a celebrity: Fans at Yankee Stadium mobbed him after a 1966 game to demand autographs. But as Bouton’s diary makes clear, not everyone in the Major Leagues was happy with his presence. Critics, including the black sportswriter Sam Lacy, viewed Ashford’s boisterous style as an affront to the still-conservative sports world of the late 1960s. Some of his fellow umpires were openly jealous of the attention he received. Other umps were simply racist.

Like Satchel Paige two decades earlier, Ashford was past his prime when he got his chance in the Major Leagues. He was over 50, his eyes were no longer as sharp as they’d been and some of his questionable calls enraged American League managers, many of whom had “rarely been confronted with black authority in their lives,” as George Vecsey of the New York Times noted in 1969. After umpiring in the 1970 World Series, Ashford retired, supposedly because he was past the mandatory retirement age of 55, though Richard Dozer of the Chicago Tribune suggested Ashford had been “coaxed to step aside—ever so delicately.” In the years that followed, he worked in the baseball commissioner’s office and even appeared as an umpire in the 1976 Richard Pryor and Billy Dee Williams comedy The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings. Ashford died of a heart attack in 1980.

In today’s carefully scripted world of pro ball, there seems no place for the flamboyance of an Emmett Ashford. Yet we need his brand of ebullience more than ever to help energize a sport that’s struggling to attract new fans in the 21st century, especially among black Americans, whose interest in baseball has been dwindling for decades. “Everybody says baseball needs more color,” Ashford once joked, “and nobody can fill the bill like I can.”