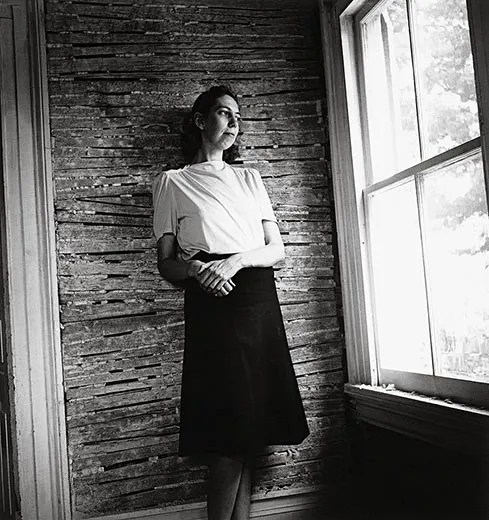

Eudora Welty as Photographer

Photographs by Pulitzer-Prize winning novelist Eudora Welty display the empathy that would later infuse her fiction

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/56/6b56efa7-c176-48a8-9fad-245997d9c36b/home-by-dark-eudora-welty-631-wr.jpg)

Eudora Welty was one of the grandest grande dames of American letters—winner of a Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, an armful of O. Henry Awards and the Medal of Freedom, to name just a few. But before she published a single one of her many short stories, she had a one-woman show of her photographs.

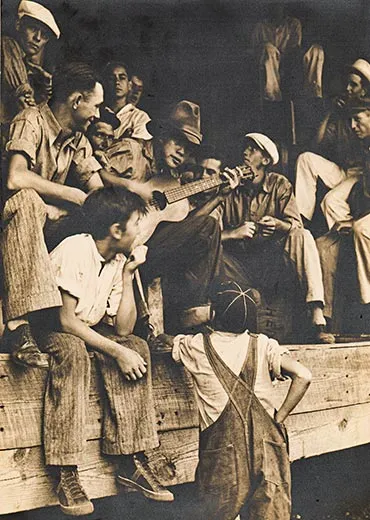

The pictures, made in Mississippi in the early to mid-1930s, show the rural poor and convey the want and worry of the Great Depression. But more than that, they show the photographer's wide-ranging curiosity and unstinting empathy—which would mark her work as a writer, too. Appropriately, another exhibition of Welty's photographs, which opened last fall at the Museum of the City of New York and travels to Jackson, Mississippi, this month, inaugurated a yearlong celebration of the writer's birth, April 13, 1909.

"While I was very well positioned for taking these pictures, I was rather oddly equipped for doing it," she would later write. "I came from a stable, sheltered, relatively happy home that by the time of the Depression and the early death of my father (which happened to us in the same year) had become comfortably enough off by small-town Southern standards."

Her father died of leukemia in 1931, at age 52. And while the comfort of the Welty home did not entirely unravel—as an insurance executive in Jackson, Christian Welty had known about anticipating calamities—Eudora was already moving beyond the confines of her family environment.

She had graduated from the University of Wisconsin and studied business for a year at Columbia University. (Her parents, who entertained her stated ambition of becoming a writer, insisted that she pursue the proverbial something to fall back on.) She returned to Jackson after her father's diagnosis, and after he died, she remained there with her mother, writing short stories and casting about for work.

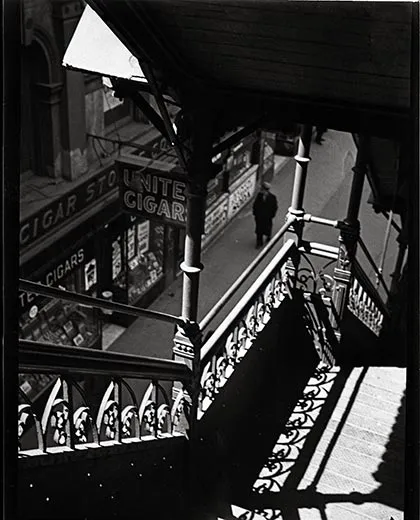

For the next five years, Welty took a series of part-time jobs, producing a newsletter at a local radio station; writing for the Jackson State Tribune; sending society notes to the Memphis Commercial Appeal; and taking pictures for the Jackson Junior Auxiliary. She had used a camera since adolescence—her father, an avid snapshot man, helped establish Jackson's first camera store—but now she began taking photography more seriously, especially as she traveled outside Jackson. In 1934, she applied to study at the New School for Social Research in New York City with photographer Berenice Abbott, who was documenting landmarks disappearing in the city's rush toward modernity. Welty's application was turned down.

It hardly mattered. Through the early '30s, Welty gathered a body of work remarkable for the photographer's choice of subjects and her ability to put them—or keep them—at ease. That is especially noteworthy given that many of her subjects were African-Americans. "While white people in a Deep South state like Mississippi were surrounded by blacks at the time...they were socially invisible," the television journalist and author Robert MacNeil, a longtime friend of Welty's, said in an interview during a recent symposium on her work at the Museum of the City of New York. "In a way, these two decades before the civil rights movement began, these photographs of black people give us insight into a personality who saw the humanity of these people before we began officially to recognize them."

Welty, for her part, would acknowledge that she moved "through the scene openly and yet invisibly because I was part of it, born into it, taken for granted," but laid claim only to a personal agenda. "I was taking photographs of human beings because they were real life and they were there in front of me and that was the reality," she said in a 1989 interview. "I was the recorder of it. I wasn't trying to exhort the public"—in contrast, she noted, to Walker Evans and other American documentary photographers of the '30s. (When a collection of her pictures was published as One Time, One Place in 1971, she wrote: "This book is offered, I should explain, not as a social document but as a family album—which is something both less and more, but unadorned.")

In early 1936, Welty took one of her occasional trips to New York City. This time she brought some photographs in the hope of selling them. In a decision biographer Suzanne Marrs describes as spontaneous, Welty dropped in at the Photographic Galleries run by Lugene Opticians Inc.—and was given a two-week show. (That show has been recreated for the centennial exhibit and supplemented with pictures she made in New York.)

That March, however, Welty received word that a small magazine called Manuscript would publish two short stories she had submitted. "I didn't care a hoot that they couldn't, they didn't pay me anything," she would recall. "If they had paid me a million dollars it wouldn't have made any difference. I wanted acceptance and publication."

That acceptance foretold the end of her photographic career. Welty used her camera for several years more but invested her creative energies in her writing. "I always tried to get her to start over again, you know, when I got to know her in the mid-1950s," the novelist Reynolds Price, another longtime friend of Welty's, said in an interview. "But she'd finished. She said, I've done what I have to do. I've said what I had to say."

In her memoir, One Writer's Beginnings, published in 1984, Welty paid respects to picture-taking by noting: "I learned in the doing how ready I had to be. Life doesn't hold still. A good snapshot stopped a moment from running away. Photography taught me that to be able to capture transience, by being ready to click the shutter at the crucial moment, was the greatest need I had. Making pictures of people in all sorts of situations, I learned that every feeling waits upon its gesture; and I had to be prepared to recognize this moment when I saw it."

She added: "These were things a story writer needed to know. And I felt the need to hold transient life in words—there's so much more of life that only words can convey— strongly enough to last me as long as I lived."

That was long indeed. Welty died on July 23, 2001, at the age of 92. Her literary legacy—not only her stories but her novels, essays and reviews—traces the full arc of a writer's imagination. But the pictures bring us back to the time and the place it all began.

T. A. Frail is a senior editor of the magazine.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)