Even 500 Years After His Death, Hieronymus Bosch Hasn’t Lost His Appeal

A trip to the painter’s hometown reminds us how his paintings remain frightfully timely

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ce/e7/cee7f4e2-3ec6-4304-9d75-6892f79d7c52/el_jardin_de_las_delicias_de_el_bosco-web-resize.jpg)

The Dutch city Hertogenbosch, colloquially referred to as “Den Bosch,” remains remarkably similar today to its layout during the medieval age. Similar enough, says mayor Tom Rombouts, that the city’s celebrated native son, painter Hieronymus Bosch, if somehow revived, could still find his way blindfolded through the streets.

This year, timed to coincide with the 500th anniversary of Bosch’s death, Den Bosch is hosting the largest-ever retrospective of the renowned and fanciful eschatological painter who borrowed from his hometown’s name to create a new one for himself. The exhibition, “Hieronymus Bosch: Visions of Genius,” held at Den Bosch’s Het Noordbrabants Museum gathers 19 of 24 known paintings and some 20 drawings by the master (c. 1450-1516). Several dozen works by Bosch’s workshop, followers, and other of his contemporaries provide further context in the exhibit.

What makes this exhibit even more extraordinary is that none of Bosch’s works reside permanently in Den Bosch. In the run-up to the exhibit, the Bosch Research and Conservation Project engaged in a multi-year, careful study of as much of the Bosch repertoire as it could get its hands on. In news that made headlines in the art world, the researchers revealed that “The Temptation of St. Anthony,” a painting in the collection of Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art -- believed not to be an actual Bosch -- was painted by Bosch himself and that several works at the Museo del Prado in Spain were actually painted by his workshop (his students.)

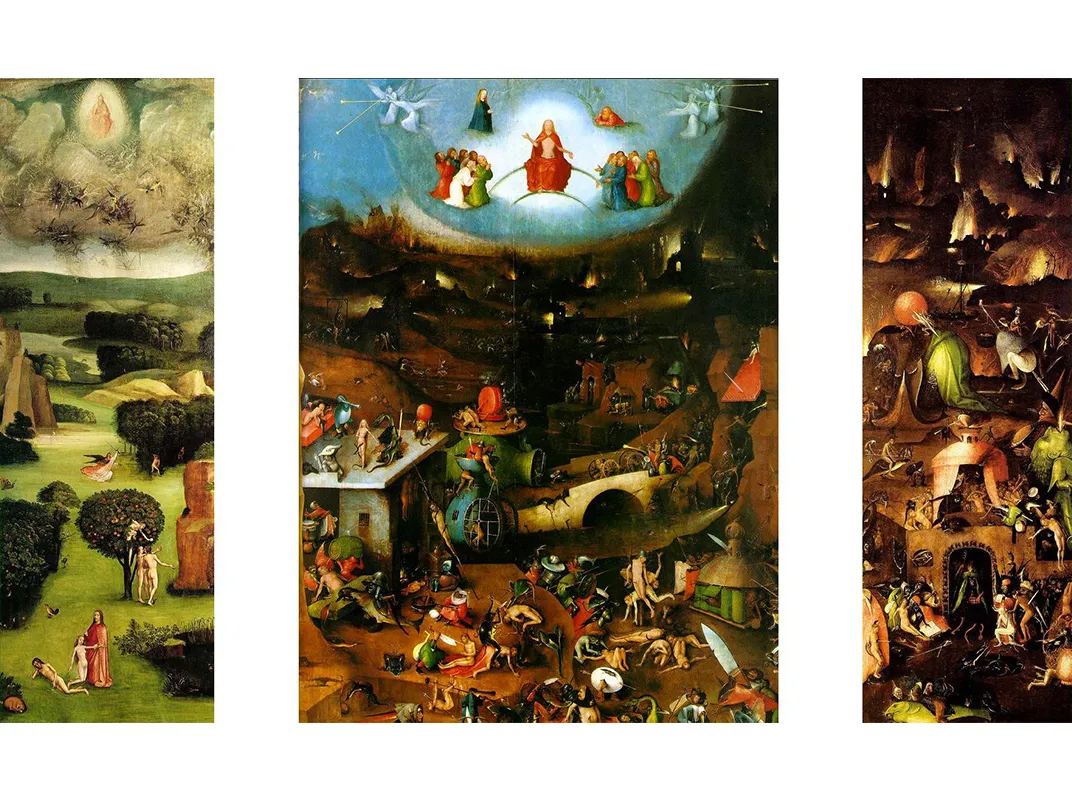

Bosch’s art is known for its fantastical demons and hybrids and he’s often discussed anachronistically in Surrealist terms, even though he died nearly 400 years before Salvador Dalí was born. In his “Haywain Triptych” (1510-16), a fish-headed creature with human feet clad in pointed black boots swallows another figure with a snake twisted around her leg. Elsewhere, in “The Last Judgement” (c. 1530-40) by a Bosch follower, a figure with a human head, four feet and peacock feathers narrowly avoids the spear of a bird-headed, fish-tailed demon dressed in armor and wearing a sword.

Bosch’s is a world in which figures are likely to wear boats as clothing or to emerge from snail’s shells; one of greatest dangers is getting eaten alive by demons; and eerily, owls proliferate. Most bizarre, perhaps, is a drawing by Bosch and workshop titled “Singers in an egg and two sketches of monsters,” in which a musical troupe (one member has an owl perched on his head) practices its craft from inside an egg.

Beyond the exhibit itself, the city is obsessed with Bosch. Cropped figures from Bosch’s works appear throughout Den Bosch, plastered to storefront windows, and toys shaped like Bosch’s demons are available for sale in museum gift shops. Other events include a boat tour of the city’s canals (with Bosch-styled sculptures punctuating the canal edges and hellfire projections under bridges), a nighttime light show projected on buildings in city center (which was inspired by a family trip the mayor took to Nancy, France), and much more.

“This city is the world of Bosch. Here, he must have gotten all of his inspiration through what happened in the city and what he saw in the churches and in the monasteries,” Rombouts says in an interview with Smithsonian.com. “This was little Rome in those days.”

When one projects back 500 years, though, it’s hard to dig up more specific connections between Bosch and his city due the lack of a surviving paper trail.

Late last year, researchers at the Rijksmuseum were able to identify the exact location of the street scene in Johannes Vermeer’s “The Little Street”, thanks to 17th-century tax records. But there is no such archive for Bosch, who kept few records that survive today. There is no indication that he ever left the city of Den Bosch, and yet no depictions of Den Bosch, from which he drew his name, seem to surface in any of his paintings or drawings.

The town does know, however, in which houses the artist, who was born either Joen or Jeroen van Aken into a family of painters, lived and worked and where his studio stood. The latter is a shoe store, and the former a shop whose proprietors had long refused to sell but, nearing retirement age, they have slated the house for sale to the city to turn into a museum, the mayor says.

Asked if Den Bosch will be able to purchase any works by Bosch, Rombouts says the city had hoped to do so, but price tags are prohibitive. “If we would have been more clever, we could have said to [the Kansas City museum], ‘May we have it on loan for eternity?’ And then said that it is a Bosch,” he says. “But we would have to be honest.”

While those at the Nelson-Atkins were surely elated to learn about the upgrade, curators at other museums who saw works they considered to be authentic Bosch’s downgraded were none too happy, said Jos Koldeweij, chairman of the Bosch Research and Conservation Project’s scientific committee.

“Sometimes it’s very emotional; sometimes it’s very academic,” he says. “At the end, it should be very academic, because museums are not art dealers. So the value in money isn’t what is the most important thing. What’s most important is what everything is.” Still, some conversations “got touchy,” he says.

In addition to the Prado works, the committee declared two double-sided panels depicting the flood and Noah’s ark at Rotterdam’s Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, as being from the workshop and dated to c.1510 to 1520. The museum, however, identifies both as Bosch and dated to 1515, the year before his death.

“This is a process of consensus, and discussions about the originality of a work will continue until everyone agrees,” says Sjarel Ex, the Boijmans’ director.

“We think that it is very necessary,” Ex says of the investigation, noting the importance in particular of Bosch’s drawings. “What do we know about the time over 500 years ago?” he adds. Just 700 drawings remain in all of Western culture which were created before the year 1500. “That’s how rare it is,” he says.

The star of Bosch’s repertoire, the Prado’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” is not part of the exhibit, although that’s unsurprising. “It’s huge and too fragile,” Koldeweij says. “Nobody reckoned it would come. It’s impossible. There are a number of artworks that never travel. So [Rembrandt’s] ‘Night Watch’ doesn’t go to Japan, and the ‘Garden’ doesn’t come here.”

“Death and the Miser” from Washington’s National Gallery of Art (c. 1485-90 in the gallery’s estimation, and c. 1500-10 in the exhibit’s tally) appears early in the exhibit and reflects powerfully the religious view that would have been ubiquitous in 16th-century Den Bosch..

In what is perhaps a double portrait, a man – the titular “miser,” a label associated with greed and selfishness—lies on his deathbed, as a skeleton opens the door and points an arrow at the man. An angel at the man’s side guides his gaze upward toward a crucifixion hanging in the window, as demons do their mischief. One looks down from atop the bed’s canopy; another hands the man a bag of coins (designed to tempt him with earthly possessions and to distract him from salvation); and yet others engage perhaps another depiction of the miser (carrying rosary beads in his hand) in the foreground as he hoards coins in a chest.

That choice between heaven and hell, eternal life and perpetual damnation, and greed and lust on the one hand and purity on the other -- which surfaces so often in Bosch’s work -- takes on an even more fascinating role in this particular work. Analysis of the underdrawing reveals that Bosch originally placed the bag of coins in the bedridden man’s grasp, while the final painting has the demon tempting the man with the money. The miser, in the final work, has yet to make his choice.

“Responsibility for the decision lies with the man himself; it is he, after all, who will have to bear the consequences: will it be heaven or hell?” states the exhibition catalog.

The same lady-or-the-tiger scenario surfaces in the “Wayfarer Triptych” (c. 1500-10) on loan from the Boijmans. A journeyer, likely an Everyman, looks over his shoulder as he walks away from a brothel. Underwear hangs in a window of the decrepit house; a man pees in a corner; and a couple canoodles in the doorway. As if matters weren’t sufficiently dour, a pigs drink at a trough -- no doubt a reference to the Prodigal Son -- in front of the house.

The man has left the house behind, but his longing gaze, as well as the closed gate and cow obstructing his path forward, question the degree to which he’s prepared to actually carry on along the straight and narrow path, rather than regressing. And his tattered clothes, apparent leg injury, and several other bizarre accessories on his person further cloud matters.

Turning on the television or watching any number of movies today, one is liable to come across special effect-heavy depictions of nightmarish sequences that evoke Bosch’s demons and hell-scapes. In this regard, Bosch was doubtless ahead of his time.

But his works are also incredibly timeless, particularly his depictions of people struggling with basic life decisions: to do good, or to do evil. The costumes and the religious sensibilities and a million other aspects are decidedly medieval, but at their core, the decisions and the question of what defines humanity are very modern indeed.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)