Exploring New York City’s Abandoned Island, Where Nature Has Taken Over

Nestled in between the Bronx and Manhattan, North Brother Island once housed Typhoid Mary, but now is an astonishing look at a world without humans

In the heart of New York City lies an abandoned island. Although it is clearly visible to commuters on the Bronx’s I-278 or passengers flying into La Guardia airport, few people are even aware of its existence. If anything, they have only heard that the infamous Typhoid Mary spent her final years confined to a mysterious island, situated somewhere within view of the city skyline. But even that sometimes seems the stuff of rumor.

Until 1885, the 20-acre spot of land—called North Brother Island—was uninhabited, just as it is today. That year saw the construction of the Riverside Hospital, a facility designed to quarantine smallpox patients. Workers and patients traveled there by ferry from 138th Street in the Bronx (for many of the latter, it was a one-way trip), and the facility eventually expanded to serve as a quarantine center for people suffering from a variety of communicable diseases. By the 1930s, however, other hospitals had sprouted up in New York, and public health advances lessened the need to quarantine large numbers of individuals. In the 1940s, North Brother Island was transformed into a housing center for war veterans and their families. But by 1951, most of them—fed up with the need to take a ferry to and from home—had chosen to live elsewhere. For the last decade of its brief period of human habitation, the island became a drug rehabilitation center for heroin addicts.

Mere decades ago, North Brother Island was a well-manicured urban development like any other. Judging from aerial photos taken in the 1950s, the wildest things there were a few shade trees. In those years, North Brother Island was covered by ordinary roads, lawns and buildings, including the towering Tuberculosis Pavilion built in the Art Moderne style.

Eventually, however, the city decided it was impractical to continue operations there. The official word was that it was just too expensive, and plenty of cheaper real estate was available on the mainland. When the last inhabitants (drug patients, doctors and staff) pulled out in 1963, civilization’s tidy grasp on that speck of land began coming undone.

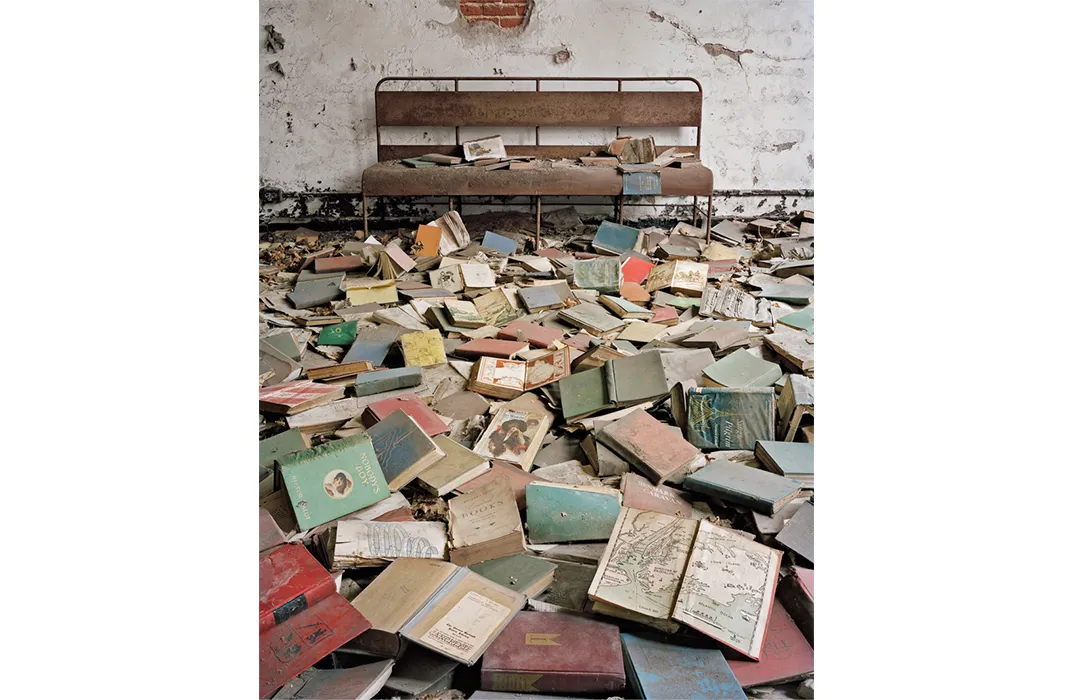

Nature quickly got to work. Sprouting trees broke through sidewalks; thick sheets of vines tugged at building facades and spilled forth from windows like leaking entrails; and piles of detritus turned parking lots into forest floors. The East River insistently lapped at the island’s fringes, eventually wearing down barriers and swallowing a road that once circled its outer edge, leaving only a manhole cover and a bit of brick where veterans and nurses once strolled.

The island has remained free from human influence in part because the city forbids any visitors from going there, citing safety concerns. Now, however, New Yorkers and out-of-towners alike have the opportunity to explore North Brother Island. Not by boat and foot, that is, but through a meticulous photographic study of the place, published this month by photographer Christopher Payne.

Like many New Yorkers, for most of his life Payne was unaware of North Brother Island. He first heard of it in 2004, while he was working on a project about shuttered mental hospitals. North Brother Island seemed like a natural progression in his artistic exploration of abandonment and decay. In 2008, Payne finally secured permission from the Parks and Recreation Department to visit and photograph the island. From that first trip, he was hooked. “It was an incredible feeling,” he says. “You’re seeing the city, you’re hearing it, and yet you’re completely alone in this space.”

For the next five years, Payne paid the island some 30 visits, ferried out by a friend with a boat, and often joined by city workers. He photographed it in every season, every slant of light and every angle he could find. “I think it’s great that there’s a place out there that’s not developed by the city—one spot that’s not overtaken by humanity and is just sort of left to be as it is,” he says, adding that the city recently declared North Brother Island a protected nature area.

Few relics of the former residents exist, but Payne did manage to uncover some ghosts, including a 1930 English grammar book; graffiti from various hospital residents; a 1961 Bronx phone book; and an X-ray from the Tuberculosis Pavilion. Mostly, though, traces of the individuals who once lived in the dorms, doctors’ mansions and medical quarters have been absorbed into the landscape—including those of the island’s most famous resident, Mary Mallon. “There really isn’t much left of the Typhoid Mary phase,” Payne says.

In some cases, the carpet of vegetation has grown so thick that the buildings hiding underneath are completed obscured from view, especially in summer. “There was one time when I actually got stuck and just couldn’t go any further without a machete or something,” Payne says. “In September, it’s like a jungle.”

Eventually, Payne came to see the island as a Petri dish of what would happen to New York (or to any place) if humans were no longer around—a poignant thought in light of growing evidence that many of the world’s coastal cities are likely doomed to abandonment within the next century or so.

“Most people view ruins as if they were looking into the past, but these buildings show what New York could be years from now,” Payne says. “I see these photographs like windows into the future.”

“If we all left,” he says, “the entire city would look like North Brother Island in 50 years.”

North Brother Island: The Last Unknown Place in New York City is available new on Amazon for $28.93. For those based in New York City, author Christopher Payne will be hosting a lecture and book signing on Friday, May 16, at 6:30 pm at the General Society of Mechanical Tradesmen of New York. Rumor has it, Payne notes, that a former North Brother Island resident or two might turn out for the event.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/2b/572b935f-4572-40c9-bfe6-bf07f80ee366/payne_nbi_beach_at_dusk.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6d/3e/6d3ed532-cf79-4021-886a-9ef450b9a2bc/payne_nbi_church_front.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/88/2288238c-ce63-4620-9cec-a53caf190bf8/payne_nbi_male_dormitory.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/81/4581982f-6bcc-4873-8c08-f614cc6ee721/payne_nbi_nurses_home.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)