Extreme Running

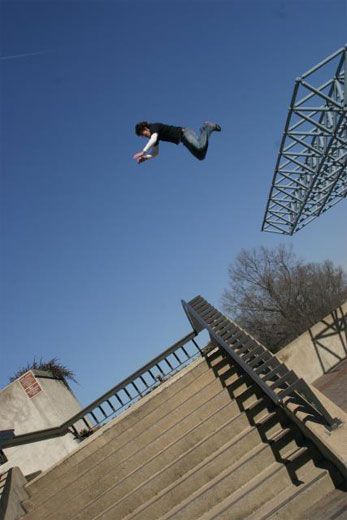

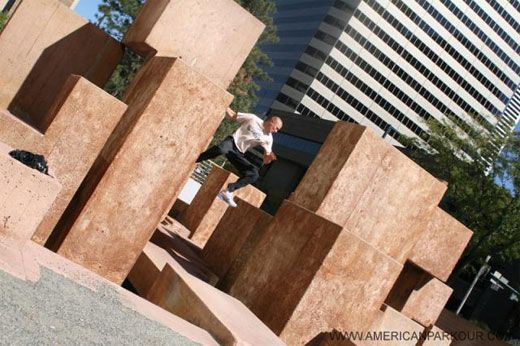

Made popular by a recent James Bond film, a new urban art form called free running hits the streets

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/freerunning6.jpg)

Sébastien Foucan is built like a soccer player, possessing the kind of physique that falls somewhere between a meaty-thighed sprinter and a sinewy marathoner. The Frenchman keeps his hair shaved close, like so many of the athletes that Europeans call "footballers."

His offensive moves, however, aren't those of a forward or a midfielder. Foucan is one of the creators of an entirely new tandem of extreme sports—or art forms, as he says—called "parkour" and "free running." Together they're redefining the way that some people interact with their physical environments.

Approximately 17 million U.S. moviegoers got a crash course in Foucan's art courtesy of the 2006 James Bond flick "Casino Royale," which opens with a jaw-dropping chase scene that has the athlete hurdling over obstacles in his path and leaping like a cat between precarious perches—including, at one point, two construction cranes.

To the uninitiated, he may resemble a mere Hollywood stuntman in computer-enhanced glory. To those in the know, however, Foucan's performance is clearly something real, raw and primal.

Mark Toorock, a Washington, D.C., resident who runs the American Parkour Web site, americanparkour.com, says the difference between a pure free run and one compiled through special effects is glaring. "Every molecule of [Foucan's] body is screaming alive," he says.

Similar video clips—usually of men aged 16 to 30—abound on the Internet. They depict human action figures who vault over and through railings, scale walls and turn flips by pushing off a vertical structure with a hand or foot. The best, like Foucan, do even more daring feats: in a film called "Jump Britain," he long-jumps across a 13-feet-wide gap in the roof of Wales' Millennium Stadium, some 180 feet above the ground.

All these risk-takers see their environment, which is typically urban, as a giant obstacle course waiting to be surmounted. The way they tackle it can vary greatly, however—a fact that in recent years has led practitioners to distinguish between parkour and free running, which began as interchangeable terms. Those who conquer turf in an efficient, utilitarian manner are said to be doing parkour and are called "traceurs." Those who add expressive, acrobatic flourishes are said to be free running.

"A lot of this stuff we've seen and has been done before for movies and chase scenes because it is so instinctual as a way to get around objects quickly," says Levi Meeuwenberg, a 20-year-old free runner from Traverse City, Michigan. "But now, it has its own background and name."

Parkour and free running emerged from Lisses, a Paris suburb where Foucan and his friend David Belle grew up. Belle's father, a firefighter and Vietnam veteran, had trained in an exercise regimen based on the methods of physical education expert Georges Hébert, which were meant to develop human strength (and values) through natural means: running, jumping, climbing and so forth.

Inspired by the techniques, Belle began playing around on public surfaces with friends, including Foucan, in the early 1990s. They called their efforts "parkour," from the French "parcours," meaning "route." (Hebert's methods also spurred the development of the "parcourse," or outdoor exercise track.)

"I didn't know what I was looking for when I was young," says Foucan. "Then I started to have this passion."

Shortly after the turn of the millennium, Belle and Foucan's playful assaults on urban facades surfaced in the public consciousness. In 2002, a BBC ad showed Belle sprinting across London's rooftops to get home from work. "There was a huge reaction," says English filmmaker Mike Christie. "No one really identified it as a sport, but I think it caught most people's eyes."

A year later, Britain's Channel 4 premiered a documentary, "Jump London," that Christie had directed on this new phenomenon. Loaded with footage of Foucan and other French traceurs bounding off London's edifices, it introduced the term "free running," which filmmakers thought to be a suitable English translation of "parkour."

According to Christie, an estimated 3 million viewers tuned in for the project's first screening, and it was subsequently exported to 65 additional countries for broadcast. Almost overnight, the practice exploded on the Internet. Toorock, who lived in Britain at the time, recalls that a local parkour Web site he was affiliated with, called Urban Freeflow, doubled its membership in a matter of weeks.

People used sites like this to meet others interested in group training sessions and "jams," where traceurs convene in one spot to do full-speed runs together, each lasting several seconds to several minutes.

By the time Christie's sequel, "Jump Britain," reached the airwaves in 2005, the United Kingdom had become a breeding ground for traceurs. Meanwhile, Toorock, who had relocated back to the United States, was founding his own parkour community, and the nascent video site YouTube was carrying images of the sport far beyond its European birthplace.

Nowadays, the practice pops up in shoe commercials, feature films, public parks, video games and even on concert stages. While the community now distinguishes between the two forms, crediting Belle with the creation of parkour and Foucan with free running, both types still boast the same roots, requirements and rewards. All a person needs for either is a sturdy pair of shoes and guts of steel. The results can include increased physical fitness, new friends and even a changed outlook on life.

"You learn to get over physical obstacles in parkour, and then come the mental ones," says Toorock, who also runs parkour training classes at D.C.'s Primal Fitness and manages a troupe of professional traceurs called The Tribe. "When life throws you something, you think, 'I can get over this, the same way that brick walls no longer confine me.'"

For Meeuwenberg (a Tribe member), the pursuits have become lucrative. Last year, he was one of six traceurs (along with Foucan) that Madonna tapped to join her 60-date “Confessions World Tour,” which featured parkour and free running elements that she'd previously showcased in her 2006 video for the song "Jump."

In this format and other commercial work, the performers are executing a routine that may use parkour or free running skills but is divorced from their guiding principles of freedom and creative exploration of one's environment, Meeuwenberg says. The real thing usually happens outdoors, and is a longer, more fluid event than what's shown in the choppy highlight reels that litter the Internet.

Meeuwenberg has been a traceur for less than four years and has found more than a paycheck in the practice; it's also tamed his fears and bolstered his self-confidence. Foucan says his favorite aspect of his art is that it affords him a feeling of connectedness to his surroundings—a rare relationship in today's industrialized landscape.

For Toorock, the two sports are a return to basics. "We're not making something up; we're finding something we lost," he says. "That's how we learn about things around us: we touch them, we feel them." When he trains traceurs, he starts from the ground up. In addition to working heavily on conditioning, his students learn how to roll out of jumps, land on a small target (called "precision") and eliminate stutter-steps before performing a vault, a technique for springing over an object.

A beginner will often see clips online and think he can immediately hurdle across rooftops without first cultivating basic skills, says Toorock. But without humility, patience and the proper foundation, a novice can seriously injure himself. Even the mighty Foucan, who makes his living doing things that have dazzled millions of people across the world, stresses that the most important thing for traceurs to remember is that it's not about impressing people.

"Do it for yourself," he says.

Jenny Mayo covers arts and entertainment for the Washington Times.