Family of Man’s Special Delivery

It took three generations to produce Wayne F. Miller’s photograph of his newborn son

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Indelible-Image-Wayne-F-Miller-631.jpg)

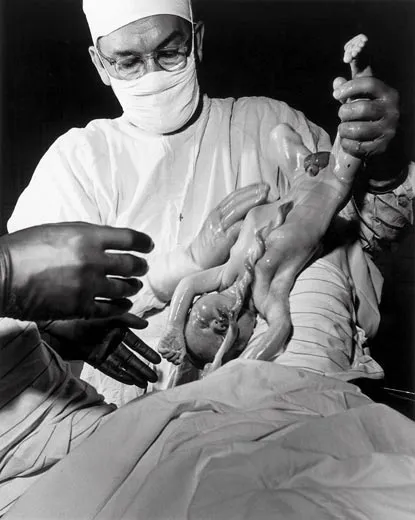

Of the 503 photographs by 273 photographers that were in Edward Steichen's landmark "Family of Man" exhibition in 1955, one may best reflect the show's title. Made on September 19, 1946, by Wayne F. Miller, it depicts the moment of birth—a doctor bringing into the world a baby boy, still attached to his mother by the umbilical cord, glistening with amniotic fluid and as yet unaware that a fundamental change has taken place.

The baby is David Baker Miller, the photographer's son, and the person least seen but most essential is Miller's wife, Joan. Many fathers, including me, have photographed their children being born, but Miller had already developed an extraordinary gift for capturing the intimate impact of such universal dramas as war and renewal—a gift that would sustain a photojournalism career spanning more than 30 years, including some 150 assignments for Life magazine. And what made the photograph especially apt for "The Family of Man" is that the doctor delivering the Millers' son was the child's grandfather, Harold Wayne Miller, then a prominent obstetrician at St. Luke's Hospital in Chicago.

"My father was proud of his work," Wayne Miller, now 90, told me during a recent visit to his 1950s-modern glass-and-redwood house in the hills above Orinda, in Northern California. "So he was happy to have me in there with my camera." (The senior Miller died in 1972 at age 85.)

I then asked Joan Miller, still youthful-looking at 88, how she felt about having her father-in-law as her OB-GYN. "Oh, I felt like a queen," she said. "He gave me the best care. Three of my children were delivered at St. Luke's, and when we moved to California and I had my fourth, I had to get used to being just another patient."

Though all went well with David's birth, there had been something of an Oedipal competition leading up to it.

"Wayne's father gave me all sorts of things to speed up the delivery," Joan recalls. "He wanted the baby to be born on his birthday, which was the 14th."

But young David was not to be hurried, and was born five days later—on Wayne's birthday. Now 62 and a software and hardware designer and entrepreneur, David doesn't think of himself as the famous subject of an oft-reprinted photograph (including in the recent book Wayne F. Miller: Photographs 1942-1958). "It's just something that happened," he says. "Being the child of a photographer, you kind of grow up with pictures being taken. The drill is, 'Don't screw this up, I have to sell this photograph.' " (David said he tried to photograph the birth of the first of his three daughters, by Caesarean section, but fainted.)

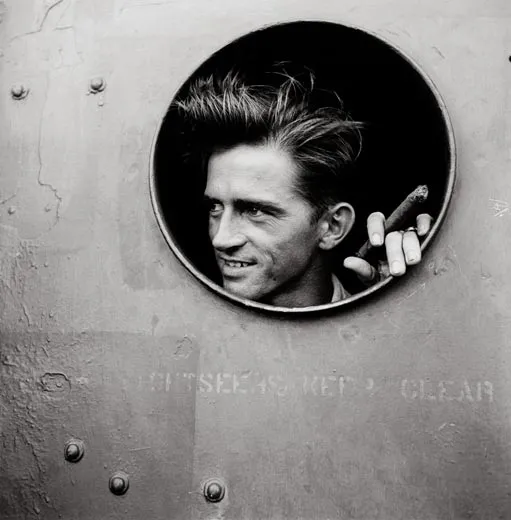

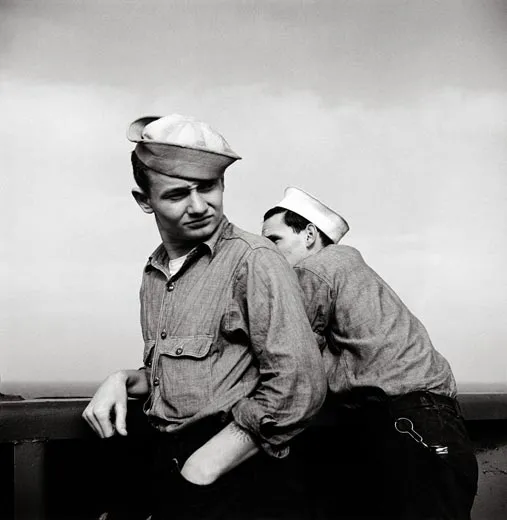

Wayne Miller also was born in Chicago, in 1918, and he attended the University of Illinois at Urbana; he studied photography at the Art Center in Pasadena, California, but left because of the school's emphasis on advertising work. Six months after Miller was commissioned in the Navy in 1942, he began what would be a long association with Edward Stei-chen, one of the titans of 20th-century American photography.

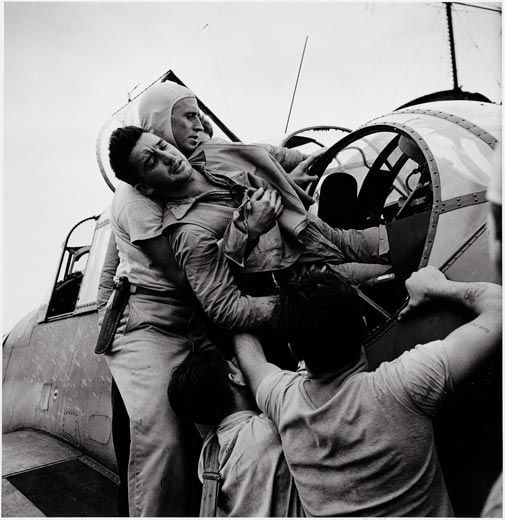

At the Navy Department in Washington, D.C., Miller managed to get some of his pictures in front of Adm. Arthur Radford, who would command Carrier Division 11 in the Pacific (and become, in the Eisenhower administration, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff). Radford recommended that Miller meet with Steichen, who had been assigned to assemble a small team of Navy officers to photograph the Navy at war.

"Quick on the trigger," as he describes himself, Miller headed to New York City, met with Steichen and was hired as the youngest member of what became an elite five-man group.

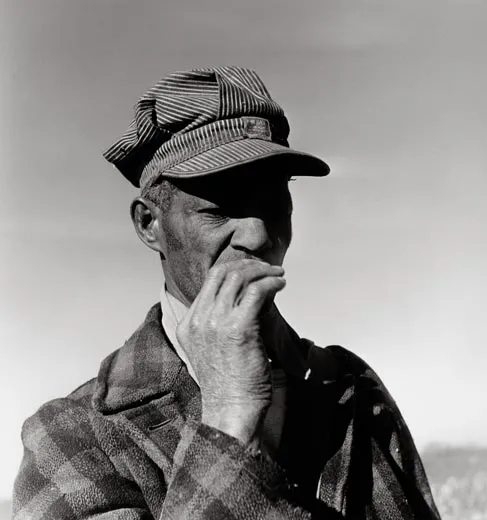

"Steichen got us all together once," says Miller, "and we never met as a group after that. We had complete carte blanche to use military transportation, to go anywhere and photograph anything." But Steichen, while making extraordinary photographs himself, kept his eye on what the others were doing. "Steichen was a father figure to me," Miller says. "He was a fascinating teacher, never criticizing, always encouraging." On the wall of Miller's studio is a photograph of his mentor, late in his life, bending down over a potted redwood seedling in his Connecticut greenhouse.

The young officer saw plenty of action at sea and made an impressive contribution to Steichen's memorable project. (He is the last of the group still living.) But he also has fond recollections of going to Brazil to photograph a mine that provided most of the quartz crystals for military radios: the U.S. chargé d'affaires said he couldn't take pictures of the facility, "so for the next three weeks I was forced to spend most of the day on the beach," he says with a smile, "and most of the night partying."

In the Pacific, Miller learned to light tight situations aboard ship simply by holding a flashbulb at arm's length. This proved to be just the right approach in the delivery room when his son was born. Steichen, who became director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City after the war, organized "The Family of Man"—with Miller's help—as an appeal for cross-cultural understanding. It was Steichen who chose Miller's picture. "He had a tremendous feeling of awe about pregnancy and procreation," Miller says. "He was in love with every pregnant woman."

Most of the photographs in "The Family of Man" gained some measure of immortality, but the picture of the brand-new Miller baby may have the longest life of all. A panel led by the astronomer Carl Sagan included it in the things to be carried forever into the vastness of space aboard the two Voyager spacecraft. In Sagan's book Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record, the picture is described simply as "Birth."

Owen Edwards, a former exhibition critic for American Photographer, is a frequent contributor to Smithsonian.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)