Fashion Faux Paw

Richard Avedon’s photograph of a beauty and the beasts is marred, he believed, by one failing

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/indelible_umbrella.jpg)

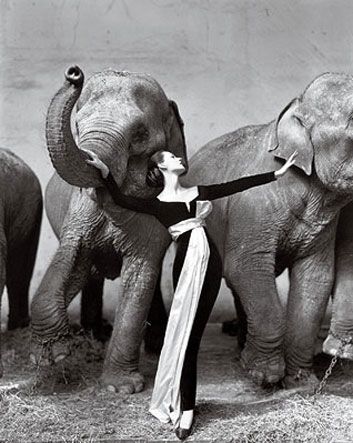

Richard Avedon, who died last October while on assignment for the New Yorker, was never completely satisfied with his most famous fashion photograph. A few years ago, at the opening of a San Francisco exhibition of pictures he made for Harper's Bazaar in the 1940s and '50s, I stood with him before a very large print of his 1955 picture Dovima with Elephants. Avedon shook his head.

"The sash isn't right," said the man who, along with Irving Penn, set the gold standard for American fashion photography. "It should have echoed the outside leg of the elephant to Dovima's right."

There is nothing unusual about an artist looking back on a defining work and regretting that it isn't better, but for Avedon's admirers the self-criticism may be baffling. For many connoisseurs of his magazine work, this image, with its astonishing juxtaposition of grace and power, is among the most perfect examples of a distinct form. Yet though it was included in several books of his work—among them Woman in the Mirror, which is being published this month—it is conspicuously absent from the 284 photos (including three of Dovima) reprinted in the one he called An Autobiography.

Far be it from me to tell a man what to put in his autobiography, but this is a picture that tells an eloquent tale, about the allure of fashion, about invention, about Avedon himself and about the kind of women who were the goddesses of their day. Dovima, half Irish and half Polish, was born Dorothy Virginia Margaret Juba in 1927 and raised in the New York City borough of Queens. At 10 she contracted rheumatic fever, and she spent the next seven years confined to her home, taught by tutors. She might have been just another beautiful young woman in New York, destined to live out a life of quiet aspiration, but one day, as she waited for a friend in a building where Vogue had offices, she caught the eye of one of the magazine's editors. Test shots were made, and the next day Dorothy was in Penn's studio for her first modeling job.

Before long, she had made a name for herself—literally—taking the first two letters of her three given names. Dovima was said to be the highest-paid mannequin in the business (though models made much less then than they do today), and she was one of Avedon's favorites. "We became like mental Siamese twins, with me knowing what he wanted before he explained it," she once said. "He asked me to do extraordinary things, but I always knew I was going to be part of a great picture." After Dovima's death from cancer in 1990 at the age of 63 in Florida, where she'd been working as a restaurant hostess, Avedon called her "the most remarkable and unconventional beauty of her time."

Avedon, whose career spanned almost 60 years, had an uncanny ability to make meticulously planned action seem joyfully spontaneous. Where the great "decisive moment" photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson and his disciples stopped motion as they came upon it, Avedon set things in motion in order to reap serendipity. He was to models what George Balanchine was to ballerinas, but where the choreographer was famous for the precision of his dancers, Avedon brought the thrill of sports photography to the fashion pages.

Two influences shaped his career, and they could not be more dissimilar. He said his first "professional" work with a camera came when he was in the merchant marine during World War II and was required to make forensic photographs of seamen who had died. These records called for an utterly unaffected approach that later informed a portrait style some have called unkind, even merciless.

The Russian émigré art director Alexey Brodovitch first published the young Avedon's fashion photographs in Harper's Bazaar. Brodovitch, who was also a direct influence on Penn, loved energy and motion as well as pictures that implied an ongoing story. He championed photographers who, like Martin Munkacsi of Hungary and France's Cartier-Bresson, prowled city streets to preserve, as if in bronze, people riding bikes and jumping over rain puddles. Munkacsi's pictures of a model running on the beach in Bazaar marked a revolutionary break with the equipoise of traditional fashion photography, and Avedon joined the revolt with a fervor that lasted a lifetime.

Dovima with Elephants was one in a series of pictures Avedon began making in Paris in 1947, the year of Christian Dior's "new look," when the City of Lights was again shining as the center of the fashion world. With a rookie's zeal, Avedon took his models into the streets to create cinematic scenes. Gathering in the frame of his Rolleiflex street performers, weight lifters, laborers and a young couple on roller skates, he gave fashion a demotic energy it never had before. I have been to more than a few Avedon fashion shoots, where his irrepressible enthusiasm infected everyone in the studio, from jaded hairstylists to blasé supermodels. In his Parisian pictures from the late 1940s and '50s, the joie de vivre is the expression of a young man's delight at being where he was, doing what he was doing.

Brodovitch told his photographers, "If you look through your camera and see an image you've seen before, don't click the shutter." With pages to fill month after month, this was an impossible demand. But when Avedon took Dovima to the Cirque d'Hiver on a hot August day, put her in a Dior evening dress, arranged its white silk sash to catch the natural light and stood her in front of a row of restive elephants—an imperturbable goddess calming the fearsome creatures by the laying on of perfectly manicured hands—he came back with a truly original picture that still reverberates with the power of myth.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)