Writing in the Public Eye, These Women Brought the 20th Century Into Focus

Michelle Dean’s new book looks at the intellects who cut through the male-dominated public conversation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0a/b3/0ab36d93-0ff8-4a53-ae1c-6266f9b814f0/anna.jpg)

“So there you are” read the kicker on Dorothy Parker’s first, somewhat hesitant review as the newly appointed theatre critic for Vanity Fair. An exploration into musical comedies, the article ran 100 years ago this month—a full two years before American women had the right to vote, when female voices in the public sphere were few and far between. It wouldn’t take long, just a few more articles, for Parker’s voice to transform into the confident, piercing wit for which she’s now famous.

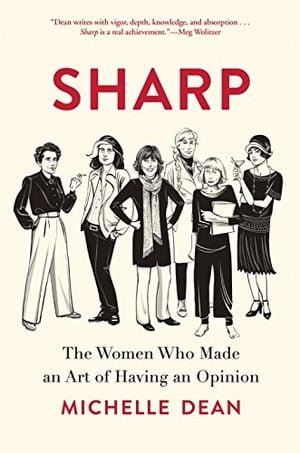

In her new book, Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion (April 10, Grove Atlantic), author Michelle Dean mixes biography, history and criticism to examine how female intellects and critics of the 20th century, like Parker, carved out a space for themselves at a time when women’s opinions weren’t entirely welcome in the national conversation. What drew readers to these women, and what sometimes what repelled them, was their sharpness. As Dean described in an interview, it’s a tone that proved “most successful at cutting through a male-dominated atmosphere of public debate.”

Dedicating individual chapters to each of the ten women she profiles, and a few to illustrate their overlap, Dean lays out a constellation of political thinkers and cultural critics. Often, these women are seen as separate from one another, but the book puts them in conversation with each other. After all, several of the women “knew each other or had personal connections, or wrote about the same things at the same times, or often reviewed each other,” Dean said. Parker leads the pack because, as Dean explained, she was “somebody everybody had to define themselves against…the type of writer that they represent wouldn’t exist without her.”

The role of the 20th century public intellectual to shape political discourse, and that of the critic to define and assess the national culture was primarily dominated by men, from Saul Bellow to Dwight MacDonald to Edmund Wilson. The women Dean covers used their intellect to stake out a place for themselves in the conversation and on the pages of major magazines like The New Yorker and the New York Review of Books where the American public first got to know them. These publications offered the women of Sharp a place to explore and defend their ideas, including Hannah Arendt’s “the banality of evil,” inspired by her reporting on the trial of Holocaust architect Adolf Eichmann and the concept of “camp” aesthetics, first codified by Susan Sontag in the Partisan Review. They critiqued the merits of each other’s work—in the New York Review of Books, Renata Adler tore apart Pauline Kael’s film criticism—and inspired new writers—a young Kael remembered being struck by the protagonist of Mary McCarthy’s novel, The Company She Keeps. Ultimately, these women influenced the conversation on topics that ranged from politics, film, photography, psychoanalysis to feminism, to name just a few.

Sharp

Sharp is a celebration of a group of extraordinary women, an engaging introduction to their works, and a testament to how anyone who feels powerless can claim the mantle of writer, and, perhaps, change the world.

Dean maintains that, while the women may have been outnumbered by their male counterparts, they weren’t outsmarted by them—and they certainly weren’t deserving of the sidelined positions historically given to them. “The longer I looked at the work of these women laid out before me, the more puzzling I found it, that anyone could look at the history of the 20th century and not center women in it,” she writes.

The published debates often grew out of or gave way to personal ones occurring at parties and soirées and in private correspondence—where gossipy letters between writers were frequently about their peers. The Algonquin Round Table, a group of critics, writers and humorists who lunched daily at Manhattan’s Algonquin Hotel, counted Parker among its founders. Reports of the banter, wisecracking and wits frequently appeared in gossip columns. At parties, the New York intellectuals relished trading barbs and jabs.

Dean said she’s been fascinated by these women and the reactions they provoked since she was in graduate school, where she began to explore and shape her own voice as a writer. Her classmates would label the women “mean and scary,” when to her, honest and precise seemed like more suitable terms. And, as Dean said, “In spite of the fact that everybody claimed to be scared of them, everybody was also very much motivated by or interested in their work.” Now an award-winning critic herself, she’s spent the past few years covering these women for several of the same publications they wrote for, dissecting Arendt and McCarthy’s friendship for The New Yorker or Dorothy Parker’s drinking for The New Republic, where Dean is a contributing editor.

In the introduction, Dean writes, “through their exceptional talent, they were granted a kind of intellectual equality to men other women had no hope of.” But that didn’t mean they were easily accepted into the boys’ club of the day. After The Origins of Totalitarianism, which sought to explain and contextualize the tyrannical regimes of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, Arendt became a household name. In response, some sniping male writers accused her of being egoistic and arrogant.

When their fellow male peers acknowledged the importance and merit of the women’s work, the men who felt threatened by the women’s criticisms would demean their successes. In 1963, after publishing her novel The Group, Mary McCarthy endured brutal criticism in the New York Review of Books from Norman Mailer, who was nonetheless still drawn to her writing. In criticizing women’s work, Dean said, Mailer “would use this extreme language and try to [negatively] characterize them in print, but privately he was always trying to solicit their [intellectual] affections in one way or another.”

Even when the women were celebrated, their work was in some ways diminished. Joan Didion, who’s best known for her personal essays and memoirs, also wrote widely read narratives about politics, like her scathing profile of Nancy Reagan, then first lady of California, in the Saturday Evening Post. In remembering her career, “the politics essays and the reporting are shuffled indoors, they want to talk about the personal essays so that trivialization of the work goes on even with women who are, as in Didion’s case, undoubtedly respected,” said Dean.

Despite their smarts, these intellectual giants were evolving thinkers with flaws. Seeing their errors—and how they learned from them or didn’t—is a fascinating element of Sharp. “There's a tendency to deliver [these women] to us as geniuses already fully formed, and in most respects that’s not the case,” said Dean. While the women were ready to be wrong in public—part and parcel of being intellectuals and critics—they were frequently surprised by the responses they received: “They often seemed to think of themselves as not saying anything particularly provocative, and then the world would react [strongly].”

Though the women’s frames of reference offered an expansion of the period’s narrow white, male perspective, they still had limits of their own. Besides a brief mention of Zora Neale Hurston, the women in the book are all white and from middle-class backgrounds, and several of them are Jewish. “They could have trouble acknowledging the limitations of their own frame on their work,” explained Dean. One example she provides is journalist Rebecca West’s coverage of a lynching trial in the 1940s South. Despite the clear racism throughout the crime and trial, West had trouble grasping and conveying the role it played. Dean writes, she “had waded into waters that were already better covered and understood by other, mainly black writers.” The brilliant Arendt controversially argued against desegregation in the Jewish magazine Commentary, citing her belief that private citizens should be able to form their own social circles free from government interference. She eventually recanted her views, persuaded by Ralph Ellison, author of Invisible Man, to whom she wrote, “Your remarks seem to me so entirely right, that I now see that I simply didn’t understand the complexities of the situation.”

To a modern reader, these outspoken, opinionated women might seem like obvious feminists, but they had tricky and varied relationships to the movement. Women within the feminist movement certainly hoped these public figures would align themselves with the cause, and felt some resentment when they didn’t—or didn’t do so in a prescribed way. Nora Ephron, who reported on the infighting between feminists, faced some backlash for noting Gloria Steinem’s crying in frustration at the 1972 Democratic National Convention. Still, her style worked so well in covering the cause because “she could be cutting about the movement’s absurdities and ugliness, but she was doing so from the position of an insider,” writes Dean.

Others, like Arendt, didn’t see sexism and patriarchy as the pressing political issue of her time, and Didion, for instance, was turned off by what was somewhat unfairly labeled a monolithic movement.

The Sharp women who did identify with the movement didn’t always have a smooth relationship with mainstream feminists either. Women’s rights activist Ruth Hale criticized West, who wrote for the suffragette newsletter the New Freewoman, as defining herself by her tumultuous, romatic relationship with writer H.G. Wells, rather than as a strong feminist herself. “There seems to be no way you can be both a writer who reflects her own experience and satisfy them, it's just impossible,” Dean says about her subject’s experience and that of the following generations of sharp women writers.

The resistance of some of Sharp’s women to the movement strikes at a central tension in feminism: the collective is frequently at odds with the individual. As critics and thinkers, “the self-definition as an outsider was kind of key for these women,” explains Dean. They struggled when “they arrived in setting where they were expected to conform to the group.” It wasn’t so much that they disagreed with feminism and its tenets, but that they resisted being labeled and constrained.

As they followed their passions and sparred with their peers, the women of Sharp didn’t ponder over how they were clearing the way for following generations. And yet, by “openly defying gender expectations” and proving their equal footing to their male peers, they did just that. Dean says she was gratified to learn from her subjects’ example that “you can pursue your own interests and desires and still manage to have a feminist effect on the culture.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.