Finding Doc Watson on Film

Searching for folk music on movies can be surprisingly difficult

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120604093034Watson-thumb.jpg)

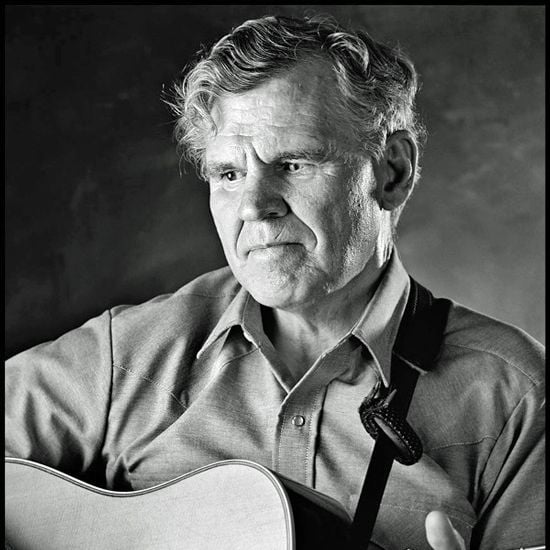

Folk music lost a legend with the passing of Doc Watson on May 29. Justly famous for his flatpicking expertise, Watson influenced a generation of guitarists, including Bob Dylan (who said his playing was “just like water running”) and Ry Cooder, who wrote this reminiscence in Wednesday’s New York Times.

Watson had close ties with Smithsonian Folkways Records, as you can learn in Wednesday’s Around the Mall posting Remembering Doc Watson, Folk Guitar Hero (1923-2012). It includes links to his albums with Clarence Ashley and Bill Monroe, as well as a clip of “Deep River Blues” from the Smithsonian Folkways instructional DVD Doc’s Guitar: Fingerpicking & Flatpicking, produced by Artie Traum’s Homespun Music Instruction.

Watson played a key role in the folk music revival of the 1960s, not just for his singing and playing, but for his eclectic taste. Purists of the time tended to slavishly recreate songs they learned from Harry Smith’s Anthology of Folk Music. Watson embraced everything: jazz, blues, country, rockabilly, pop. He gave equal weight to all genres, and found inspiration in both traditional songs and Tin Pan Alley concoctions. He helped listeners find a common thread across musical boundaries.

The guitarist recorded for a number of labels, including Vanguard, Capitol and Sugar Hill, and appeared on innumerable radio and television shows. Many of these can be found on YouTube, and like the Smithsonian Folkways link above, are mostly excerpts from larger pieces. Like “Old, Old House,” a clip from the 2008 Appalshop documentary From Wood to Singing Guitar.

The definitive Doc Watson documentary has yet to be made, and it can be frustrating catching glimpses of his performances instead of learning more about what he was like as a person. Three Homespun instructional DVDs—Flatpicking with Doc, Doc’s Guitar, and Doc’s Guitar Jam—show a more unguarded portrait of the musician.

Another good source of Watson material is Stefan Grossman’s Vestapol Videos and DVDs. Doc and Merle Watson In Concert (1980) has footage of the musicians at home. Doc Watson–Rare Performances 1963-1981 assembles clips from TV shows like “Hootenanny” and “Austin City Limits.”

It can be difficult to find folk musicians like Watson on film, the occasional “Austin City Limits” notwithstanding. It’s been over a decade since PBS offered American Roots Music, a somewhat cursory overview of “Blues, Country, Bluegrass, Gospel, Cajun, Zydeco, Tejano and Native American” styles. Public television’s American Masters series has devoted episodes to Phil Ochs and Joni Mitchell. But the genre has yet to receive the treatment it deserves.

Rural music was treated with more respect back in the 1920s, when movies were beginning to switch from silent to sound. Warner Bros. introduced its Vitaphone sound system to the public on August 6, 1926, with a program of eight short films. The only popular, as opposed to classical, title was Roy Smeck, “The Wizard of the String,” in “His Pastimes.” Smeck, whose career extended into the 1960s and beyond, played the banjo, ukulele and Hawaiian (or slide) guitar. Warners released His Pastimes on its Jazz Singer box set.

Country and rural acts appeared in a number of musical shorts of the period: Otto Gray’s Oklahoma Cowboys, The Rangers in “After the Roundup,” Oklahoma Bob Albright and His Rodeo Do-Flappers, etc. Watson told journalist Dan Miller that he switched from the Maybelle Carter “thumb lead” style of playing to flatpicking because of Jimmie Rodgers. “I figured, ‘Hey, he must be doing that with one of them straight picks.’ So I got me one and began to work at it. Then I began to learn the Jimmie Rodgers licks.” “The Father of Country Music,” Rodgers filmed a short for Columbia Pictures in Camden, New Jersey, The Singing Brakeman, in October, 1929.

In the 1930s and 1940s, “singing cowboy” movies gave a platform for rural artists like Roy Acuff, Ernest Tubb and Jimmie Davis. Similarly, “Soundies,” a precursor of sorts to music videos, could star Merle Travis or Spade Cooley. Bob Wills, another Watson favorite, appeared in over a dozen features and shorts during the period. Pete Seeger appeared in an educational short, To Hear Your Banjo Play (1947), directed by Irving Lerner and Willard Van Dyke.

Genuine folk music became harder to spot in movies during the 1950s, perhaps because a younger generation was turning to rock and roll. Fans could spot Merle Travis singing “Re-enlistment Blues” in From Here to Eternity, but often rural music was the subject of derision, as in A Face in the Crowd.

Watson’s emergence, along with the rise of individuals like Dylan and groups like Peter, Paul & Mary and The New Lost City Ramblers, helped burnish folk’s reputation. Suddenly folk musicians were everywhere on TV. Film caught up later with the Oscar-winning Bound for Glory (1976), a fanciful biopic about Woody Guthrie, and the genre was gently roasted by the Spinal Tap gang in A Mighty Wind (2003). The next Coen brothers film, Inside Llewyn Davis, recreates the 1960s MacDougall Street/Greenwich Village folk scene.

It’s a treat to see Johnny Cash perform in the otherwise mediocre Hootenanny Hoot (1963), but it seems to me that filmmakers of the time rarely captured the essence of folk music. One exception is John Cohen, a musician with The New Lost City Ramblers, photographer and writer as well as a documentarian. The High Lonesome Sound (featuring Roscoe Holcomb) and in particular Sara & Maybelle: the Original Carter Family present folk music the way it should be heard. If you can find his DVD, grab it.

This is a very abbreviated overview, one that leaves out whole swaths of performers and musical styles. Les Blank, for example, has made excellent documentaries about Louisiana and Tex-Mex music, and filmmakers like D A Pennebaker have dug deep into Americana music. There’s always more to learn, one of the best lessons listening to Doc Watson taught me.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)