Finding the Humor in History

The irreverent take on the giants of literature, science and politics could only have come from the brain of cartoonist Kate Beaton

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/kate-beaton-comic-and-portrait-631.jpg)

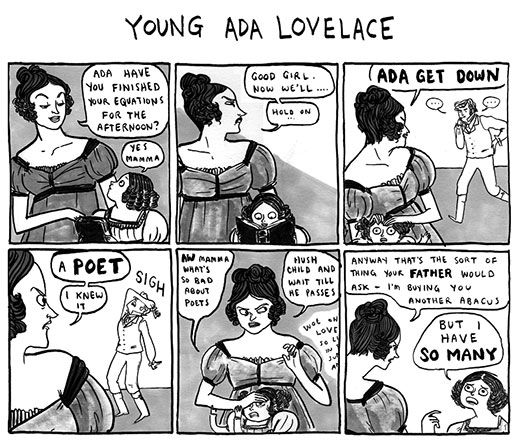

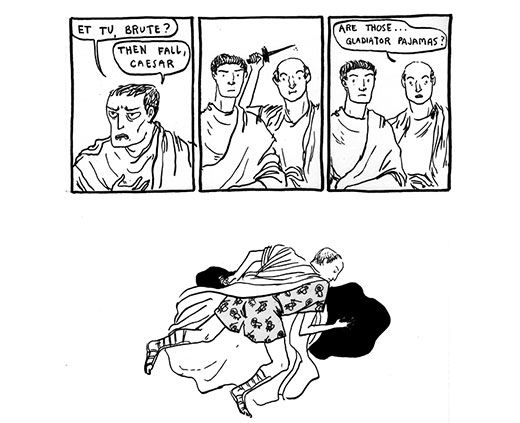

In just four years, Kate Beaton has made a name for herself as a cartoonist. She launched her webcomic “Hark! A Vagrant” in 2007 and has since published two books. Her strips, which look like doodles a student might draw in the margins of her notebook, read as endearing spoofs on historical and literary characters. In one, Joseph Kennedy overzealously goads his sons’ aspirations for presidency, and in another, the Brontë sisters go dude watchin’.

Beaton, 28, started penning comics while studying history and anthropology at Mount Allison University in New Brunswick, Canada. Her cartoons, about the campus and its professors at first, ran in the school newspaper. “I don’t know how well I ingratiated myself among the faculty,” she says. But now the New York City-based cartoonist hears of educators who serve up her witty comics as aperitifs to what might otherwise be dry lessons.

Just a few months after the release of her latest book Hark! A Vagrant, Beaton took a break from sketching Heathcliff of Wuthering Heights fame to discuss her work with us.

What do you look for in a subject? Are there certain character traits or plotlines you look for?

A certain amount of conflict makes it easier. But there are no red flags really. In general, you just sort of become very familiar with the subject and then you poke fun at it like you would a friend of yours that you know very well.

You once said that your approach is directly related to the old Gaelic-style humor of Nova Scotia. How so?

My hometown [of Mabou, Nova Scotia] is very small. It is 1,200 people or so, and it is really well known for its Scottish heritage. It was so culturally singular in a way. That culture grew because it was so isolated there for such a long time. There is just a certain sense of humor. They talk about it like it’s a thing. I read once in a book that it was a knowing wink to the human foibles of the people that you know. Usually someone is just sort of being a little hard on you or someone else, but in a friendly way. You have to live with these people. No one is a jerk about it. But it is jokes at the expense of everyone’s general humanity. You could call it small-town humor.

So what kind of research does it take to attain a friendly enough rapport with figures in history and literature to mock them in your comics?

For every character it is totally different. It is not just a character. It is the world around the character or the book or the historical thing. People take history very personally, so an event might have a second or third life depending on who is reading about it and who is writing about it and who cares about it. It is fascinating. I don’t really have a particular process. I just try to find the most credible and interesting sources that I can to read about things and I go from there.

Before you went full steam as a cartoonist, you worked in museums, including the Mabou Gaelic and Historical Society, the Shearwater Aviation Museum and the Maritime Museum of British Columbia. Do you visit museums or nose through their digital collections for inspiration?

Yeah. I recently went to the Museum of the Moving Image to see the Jim Henson exhibit here in New York. I like museums a lot. I like visiting them, more to see how they present information than the information inside. That is usually the most interesting part. What do you choose to leave in? What do you leave out? I think the idea of public history is really interesting. What people know about and what they don’t. What is part of the story publicly? Who do you make a statue of and where do you put it and why?

The bulk of my research is online, although I have quite a few books of my own. You learn how to Google the right things, I guess, either a phrase that you think will work or any kind of key words that will bring you to an essay someone wrote or to Google Books. Archive.org has all kinds of books as well. You can find a lot of university syllabi. You can find so much. Go to the Victoria and Albert Museum website. They have all kinds of costuming stuff there. I needed to find a flintlock pistol recently for a strip about pirates, and there was this person’s website. He has one for sale and has pictures of it from all angles for some collector. It was great. The Internet is pretty wonderful for that kind of thing.

How do you make a comic appeal to both someone who has never heard of the figure you are lampooning and someone who is that figure’s biggest fan?

You try and present figures as plainly as you can, I suppose. That’s why my comics got bigger than just a six-panel comic about one subject. It became six smaller comics about one subject or something like that because there is too much information to put in. Maybe the first couple might have a bit more exposition in them so that by the time you get to the bottom, you are familiar with the characters even if you don’t know them from a book or from studying them. If I did a breakdown, you could see that maybe one comic especially will hit it big with someone who doesn’t really know much about it. It might be a sight gag or something, a face or a gesture, and then one will really hopefully pay some kind of tribute to somebody who knows a bit more about it. It would still be funny but it would have a more knowledgeable joke that goes over some people’s heads, and that would be fine.

Is there someone you really want to make a comic about but haven’t figured out the hook?

Yeah. I have been reading a lot about Catherine the Great lately. But she is so larger-than-life; it is difficult to take in all of that information. In some ways, you think it would make it easier, because she is somebody that everybody knows. But she is liked by some people, disliked by others. She had some good qualities and some bad qualities. What do you pick? What do you go with? If I made, say, six comics, what would they be, from a life this large?

What has been the most surprising response from readers?

Emotional responses, definitely. I think that one of the most emotional responses was in doing one about Rosalind Franklin, the DNA research scientist whose work was stolen by James Watson and Francis Crick and put in their Nobel Prize-winning book. That was just a huge deal in the beginnings of DNA research. They didn’t give her credit for her photographs that they took of the double helix. They won Nobel Prizes, and she died. It is so tragic and awful and people really responded to it, because she is just representative of so many people you read about and you can’t believe were overlooked. The joke is respectful to her. It is not the most hilarious comic. But it does give Watson and Crick kind of a villainous role, and her sort of the noble heroine role. It is nice to see people really respond to history that way. It is nice to touch a nerve.

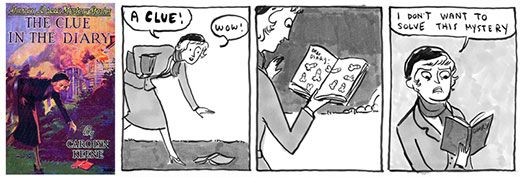

I especially like when you use Nancy Drew covers as springboards for comic strips. How did you get started with that?

I started with Edward Gorey covers. I was trying to think of a comic idea one day, and I was going nowhere. I was so frustrated, and someone on Twitter was like, check out all these Gorey covers, a collection on a website. I looked at them and thought you really could extrapolate from this theme that is on the cover and make a comic about it. So I did, and they went over really well. I started to look for some other book covers that had an action scene on the front that were available in a set. I read all of the Nancy Drew books in two weeks when I was 10 because I was in the hospital and that is the only thing that they had. I read the heck out of those books and probably remember them in a weird haze of a two-week megathon Nancy Drew reading while being sick. Perhaps that weird memory turned Nancy into kind of a weirdo in my comic.

What is on the cover is like, “Here is what’s inside.” Be excited about this. There is no abstract stuff, because kids would be like who cares. There are people doing things and that is why you pick it up. You are like, I like the look of this one. Nancy looks like she is in a real pickle.

Have you ever felt that you went too far in your reinterpretation of history or literature?

Not really. I think I toe a safe line. I don’t really get hate mail. I respect the things that I poke fun at and hopefully that shows. Earlier on, I suppose I went for the more crude humor because you are just trying to figure out your own sense of humor and what your strengths are. It takes a long time to figure out comedy, to figure out what it is that you are capable of in it and what your particular voice is in humor and comedy.

Who do you find funny?

Oh, a lot of people. The same Tina Fey, Amy Poehler crowd that everybody seems to like nowadays. But I also really enjoy the old-style humor. Stephen Leacock is one of my favorites. He was a Canadian humorist around the turn of the century. And Dorothy Parker’s poems are so good and funny. It is hard to be funny. I like to take influences from all over the board. Visually, I have a lot of collections from Punch magazine and that type of stuff, where the visual gags are so good. I respect that level of cartooning.

When you do public readings of your comics, obviously, you are in control of how they are read, where the dramatic pauses are and everything. Do you ever worry about leaving that up to the readers?

You try to engineer it in a certain way. People are going to read it the way they do. My sister reads the end of the book as soon as she starts one. It drives me crazy. Why would you read the last chapter? She can’t stand waiting for the joke or waiting for the end. I try to construct my comics in a way that no one can do that. A joke hits them in the face before they can get to the end.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)