Five Films that Redefined Hollywood

Author Mark Harris discusses his book about the five movies nominated for Best Picture at the 1967 Academy Awards

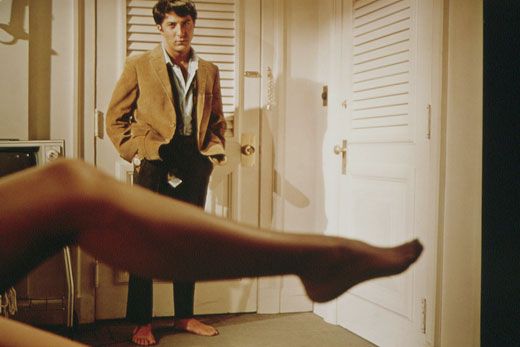

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The-Graduate-movie-631.jpg)

In 1967, the five movies nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards represented the winds of change in Hollywood. The Graduate, rejected by every movie studio, was an iconic film for a generation; Bonnie and Clyde gave a 1930s counter-culture sensation a 1960s sensibility; In the Heat of the Night captured America’s racial tensions in performances by Rod Steiger and Sidney Poitier; Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, the ultimate Hollywood “message movie,” was the final role for Spencer Tracy, the last of the Golden Age icons; and finally, Dr. Doolittle, a train wreck of a movie that showcased all that was wrong with the dying studio system.

Smithsonian.com’s Brian Wolly talked with Mark Harris, a columnist for Entertainment Weekly about his book Pictures at a Revolution and the Academy Awards.

There appears to be a returning theme in your book of “the more things change, the more they stay the same,” where quotes or passages could just as easily be written about today’s Hollywood. Which aspect of this surprised you the most in your research?

All I knew about Dr. Doolittle going into the book was that it was an expensive disaster, which I thought would make a great counterpoint to these other four movies which were not disasters and all put together did not cost as much as Dr. Doolittle. There were certain things about the way it was made that I thought really had not come into play in Hollywood until the 1980s and 1990s that I was surprised to see were alive and well in the 1960s. For instance, picking a release date before you have a finished script, not worrying that you don’t have a finished script because you just imagined the script as a variable that you didn’t have to worry about. Thinking about no matter how bad the movie is, you can solve it either by tweaking it after test screenings or a really aggressive marketing campaign. Throwing good money after bad, thinking, “Oh we’re in so deep, we just have to keep going and we’ll spend our way to a hit.”

One review I read complimented you on not going in-depth on what was happening in the United States, the protests, the politics. You only really made parallels where it actually fit, as in Loving v. Virginia. Was this intentional on your part?

I didn’t want this to be a year that changed the world book, there are a lot of those out there and some of them are really interesting. This was a book specifically about movies and changes in the movie business. But I don’t think its possible to understand why movies in 1968 were different than movies in 1963 without understanding what went on in the country during those years.

Maybe a simpler way to put it is, it’s less important what was going on in the civil rights movement than what Norman Jewison [director of In the Heat of the Night] was aware what was going on in the civil rights movement versus what Stanley Kramer [director of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner] was aware what was going on in the civil rights movement. Their different levels of engagement with what was happening in terms of civil rights both within the country and within the industry tell you a lot about why each of those movies came out the way they did.

One of the more astounding points laid out in the book, at least for someone of my generation, is that movies not only stayed in theaters for months, but that they stayed at the top of the box office for months as well. When did this shift happen? How did affect how movies are made?

I think the shift happened when aftermarkets were invented. Movies did stay in theaters for months in the 60s and 70s, and sometimes even for a couple of years if they were really big hits. The only chance that you would ever have to see a movie after it ran theatrically was network television, where it would be interrupted by commercials and where anything objectionable would be cut out. There’s not a lot of reason now to rush out to see a movie in a movie theater, and in the 1960s, there were tons of reasons.

In your book, there is a constant theme of the roles Sidney Poitier plays and how white and black America viewed race relations through him. But given the research you lay out, you seem to be more on the critical side, that Poitier played black roles that were palatable to white audiences. Is that a fair reading?

My feeling is that Poitier was facing an almost impossible situation in trying to serve his race (which is something that he very badly wanted to do), grow as an actor (which is something he very badly wanted to do), work entirely within a white power structure (which is something he had to do), and make movies. He handled it as well as anyone possibly could have. I think that there’s real sadness in the fact that by the end of the book, he reaches the apex of his career, in terms of box office success and critical acclaim.

Poitier had a stretch of four years in which he was in Lillies of the Field, A Patch of Blue, To Sir with Love, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and In the Heat of the Night, a string that made him one of the most bankable stars in Hollywood. What happened to his career after In the Heat of the Night?

There was this moment that just as white middle America completely embraced him, black America started to have less use for any black actor who was that embraced by white America. There was this sort of suspicion that if he’s that popular, he must by definition have been too accommodating. What you see when you read about Poitier after that is the story of a guy who had become deeply disillusioned with the way Hollywood worked.

I love the Mike Nichols quote about who Benjamin and Elaine [the two main characters in The Graduate] became – their parents. Yet it seems the same thing could be said for Oscar voters. The “old academy members” are the scapegoat for each questionable decision cast by the academy…and this was true in 1967 and it’s true now.

Young movie fans tend to be much more rigid and doctrinaire, because they’re the ones who say, “Well, a certain part of the electorate is just going to have to die before things change.” Eventually, the people complaining about the way things go this year will be the establishment. There’s no question that the academy votership is older than the median moviegoer.

I tend to really reject theories as if the Academy, as if it’s a single-brained entity, makes decisions one way or another. I hate the word “snubs” because it implies a sort of collective will behind something, that I don’t think is usually the case.

More things that are called snubs are actually the result of the extremely peculiar voting tabulation system that any kind of collective will, on the other hand, its completely fair to say that Academy voters have certain areas of really entrenched snobbery. I absolutely heard Academy voters say this year, point blank, that they wouldn’t vote for The Dark Knight for a best picture nomination because it was a comic book movie. You can see a history where they’ve taken a really, really long time to embrace certain genres. It really took until The Exorcist for a horror movie to get nominated, until Star Wars for a hardcore for a spaceships and laser guns, sci-fi movie to get nominated.

You write about how the organizers of the Oscars ceremony had to beg and plead with stars to show up at the event. What changed to make the Oscars a can’t-miss event for Hollywood?

Definitely some years after the period covered in my book is when it happened. The Oscars sort of hit bottom in terms of celebrity participation in the early 1970s. It was considered chic to hate awards; George C. Scott rejected his nomination and Marlon Brando rejected his Oscar. The academy at that point, seeming so old Hollywood establishment, was being rejected by a generation of new moviemaking mavericks. For a little while in the early 70s, the Oscars seemed to be at this precarious moment where they could go the way of the Miss America pageant. Then, as these newcomers became part of the establishment, lo and behold, they actually do like winning awards. It’s funny, when you start winning them, you don’t tend to turn up your nose at them quite so much. I think probably by the mid 70s, late 70s, it had kind of stabilized.

Which of the five movies you reported on is your favorite? Which do you think has the most lasting power and would be appreciated in today’s environment?

This is always a tough one, and I usually say my favorite is The Graduate, and I think its because of, ironically, one of the things that made people complain about it when it first came out, which is it has this coolness, this distance, not just from the generation of Benjamin’s parents, but between Benjamin and his generation The Graduate still plays beautifully and its also just so astonishingly crafted scene by scene in terms of everything from the acting to the direction to the cinematography to the art direction to the soundtrack being on the same page. The first hour of that movie is a shot-by-shot master class.

I’ve done a bunch of screenings over the years since the book has come out, and generally, In the Heat of the Night is the movie that people are most pleasantly surprised by. In my head, when I started the book, I positioned it as sort of an old Colombo episode. The more I watched it, the more I really became impressed by the craft in every area. The way it’s edited, the way its shot, the way its directed…and how lean it is. There are very few wasted scenes or wasted shots in that movie. When I’ve shown it to people, they have been really surprised…they’ve expected this sort of antique parable about race, and instead you get a good movie.

I sort of wish I had done this interview last year, because this year’s movies are so subpar. Are any of the movies nominated for this year’s Oscars close to being as groundbreaking as those from that year?

This year? No. I have to honestly say no. I do think they could have contrived a more exciting set of nominees than the ones they picked. The parallel I would say between ‘67 and now, I think in ‘67, a lot of people in Hollywood were beginning to get the impression that they were at the end of something, but not aware yet of the thing that replaced what was dying out was going to be. I do feel that right now, the dominant thing that’s going on right now in Hollywood, without question, is economic panic. It’s how are we going to survive internet piracy, streaming video, and TV, and people wanting their DVDs sooner that ever, is the theatrical exhibition even going to last, and I think that kind of churning panic eventually breeds something very interesting on screen. But, we’ll know what that is probably going to be about a year or two from now.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/brian.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/brian.png)