Focus on the Blues

Richard Waterman’s never-before-published photographs caught the roots music legends at their down-home best

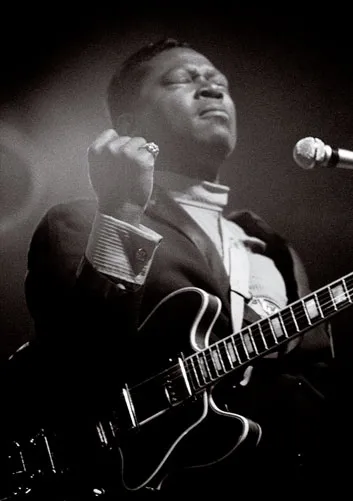

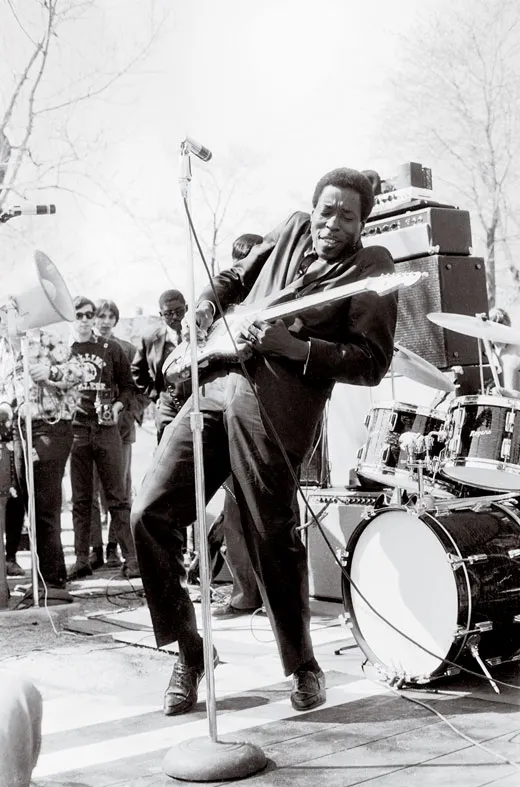

Dick Waterman’s front porch resembles many in timeless Mississippi: wicker-back rockers, a bucktoothed rake, withered hanging plants. But step through the front door and you’re in the proud, disheveled 1960s. The living-room walls are adorned with posters for long-ago concerts. Shelves swell with LPs. On tabletops and couches are stacks and stacks of vintage photographs. B.B. King and Janis Joplin, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. Waterman’s pictures of old bluesmen (and women), taken over four decades, include priceless artifacts of the music’s glory days, and until now they’ve been all but hidden.

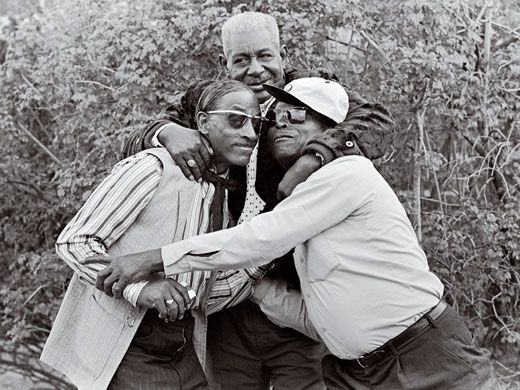

Perhaps no one alive has known more blues masters more intimately than Richard A. Waterman, 68, a retired music promoter and artists’ manager who lives in Oxford, Mississippi. He broke into the business in 1964, when he and two friends “rediscovered” Son House (guitar mentor of Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters). Waterman went on to manage a cadre of blues icons (Mississippi Fred McDowell, Skip James and Mississippi JohnHurt, among them), promoted the careers of their electrified musical progeny (Luther Allison, Buddy Guy, Junior Wells), and took under his wing a 19-year-old Radcliffe freshman named Bonnie Raitt and managed her career for about 18 years, helping her become one of her era’s reigning blues guitarists and singers.

Through it all, Waterman carried a Leica or Nikon camera and committed thousands of musicians to film, catching the magical and the mundane. Usually he just stashed the photographs in a drawer or closet. Though a relentless advocate of other artists, he never got around to publishing his own work, perhaps out of some bonebred aversion to seeing things through. “I’ve been trying to get him off his you-know-what to get these photographs out to the world,” says Raitt.

They are finally surfacing, thanks to a chance encounter in 1999. Chris Murray, director of the Govinda Gallery in Washington, D.C., was strolling down an Oxford street when he spotted a number of Waterman’s shots in a framing shop. Within hours, he and Waterman were talking about doing a book. Their project, Between Midnight and Day, is scheduled to be published next month by Thunder’s Mouth Press. Now those images, like the blues veterans they depict, are resonant again after decades in the dark. “This was no more than a hobby,” Waterman says of his photography. Despite many years in the South, Waterman’s high pitched voice is still shaded with notes of his Boston boyhood. “I never considered myself a chronicler of my times.”

“That’s like Faulkner saying that he was a farmer, not a writer,” says William Ferris, a folklorist and a former chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities. “There’s no question [Waterman] knew what he was doing and he did it systematically, like any good folklorist or documentary photographer. He is a national treasure.”

Howard Stovall, a former executive director of the Memphis-based Blues Foundation, says Waterman “had amassed an incredible body of work before it even occurred to him that there was a ‘body of work.’ ” He adds, “There’s probably no one in America who was that close to that many blues artists—with a camera in his hand.”

Waterman’s camera work is only now coming to light, but his efforts on behalf of musicians have long been recognized. “Dick helped shepherd the blues to a place in the culture that truly befits its worth,” says Raitt. He has had David-and-Goliath triumphs over record companies, extracting copyrights and royalties for blues musicians and their heirs. “In those days,” says James Cotton, the Mississippi-born harmonica master and bandleader (whom Waterman did not represent), Waterman “was the tops because he treated his artists right and he made them money.” Peter Guralnick, author of biographies of Robert Johnson and Elvis Presley, sees a connection between Waterman’s management style and his photography: “Dick’s [career] has always been about treating people fairly. I think the photographs are about trying to reflect people honestly.”

Since 1986, Waterman has made his home in the Delta, that fertile corner of northwest Mississippi known for growing cotton and bluesmen. He describes himself as one of Oxford’s token Northerners. “Every Southern town has to have a crackpot eccentric Yankee,” he says. As it happens, he lives a short drive from Clarksdale, site of the mythical “Crossroads,” popularized by Eric Clapton and Cream, where blues legend Robert Johnson supposedly traded his soul to the Devil in exchange for a wizard’s way with a guitar.

Lately, Waterman, who retired in the early 1990s from managing musicians, has had little time for relaxing on his porch. He photographs performers at blues festivals, exhibits his pictures hither and yon, and is forever offering insights to willing listeners; he appears in Martin Scorsese’s seven-part PBS documentary, The Blues, scheduled to air this month.

On a steamy July day in his living room—puddles of unopened mail and uncashed checks and a Christmas ornament resting on a breakfront testify that Waterman, a bachelor, still spends a lot of time on the road—he pulls out a favorite print of Son House, father of the blues guitar, and takes a deep breath, as if inflating his lungs with memory: “To see Son House perform. And to see him go to a place within himself that was very dark and secretive and ominous and bring forth that level of artistry. It was as if he went to 1928 or 1936 . . . He just left the building. The greatness of Son House was to look at Muddy Waters or Howlin’ Wolf or Jimmy Reed when they watched Son House and to read Son House in their faces. They would shake their heads. Buddy Guy would say, ‘That old man’s doin’ another kind of music. We can’t even go to that place.’ If the blues were an ocean distilled . . . into a pond . . . and, ultimately, into a drop . . . this drop on the end of your finger is Son House. It’s the essence, the concentrated elixir.”

He opens a drawer, and a gust of regret seems to blow into the living room. “I don’t show this to many people,” he says. He holds up a tray from a photo darkroom. “It’s very depressing.” In his hand are 150 rolls of film all stuck together, representing some 5,000 pictures from the ’60s. “I put them in a closet, and there was some sort of leak from the attic. It filled with water, and the emulsion adhered to the inner sleeves. Many, many, many rolls, gone forever.”

Those corroded strips of negatives are like forgotten songs, the ones that somehow never found their way onto a round, hard surface. Hold a sliver of film toward the light and one can discern faint streaks: tiny figures playing guitar. They are irretrievable now. But the blues is about loss, and Waterman has known his share of the blues, including a stutter (which he has overcome), past cocaine use, whirlwind relationships (he and Raitt were an item for a time) and once-simmering feuds with rival managers. He has lost legions of friends to illness and hard living. But if his life has been about anything, it has been about redressing loss and regret through the balm of rediscovery.

Late in the day, Waterman takes a drive to visit the grave of his friend Mississippi Fred McDowell. The photographer steers his old Mercedes out of Oxford, past signs for Goolsby’s World of Hair and Abner’s Famous Chicken Tenders, past the novelist John Grisham’s massive house set amid the horse pastures. The floor of the passenger’s seat is awash in junk mail and contact sheets. Within an hour, Waterman is standing in a hillside cemetery in Como, Mississippi, population 1,308. The headstone reads: “Mississippi Fred” McDowell, Jan. 12, 1904-July 3, 1972.

Plastic flowers sprout at the marker’s base, where recent visitors have left a silver guitar slide and $1.21 in change. The ash-gray slab, paid for by Waterman, Bonnie Raitt and Chris Strachwitz (the founder of Arhoolie Records), bears lyrics of McDowell’s blues classic “You Got To Move”: “You may be high, / You may be low, / You may be rich, child / You may be poor / But when the Lord / Gets ready / You got to move.”

“You talked to him about funny, stupid, absurd things that just made you pee laughing,” Waterman recalls. “Some of the most enjoyable experiences [I’ve had] were with Fred.”

Later, as he heads back to Oxford, a hazy sunset turns the air to taffy. Waterman pops in a cassette, and across the dash comes the thrilling tang of McDowell’s slide guitar. Waterman passes families on porches, a tractor in a willow’s shadows, children playing dodge ball in the dust. “We’re listening to Fred in Fred’s country,” he says. A tear appears in the corner of his eye. And on he drives.