For German Butchers, a Wurst Case Scenario

As Germans turn to American-style supermarkets, the local butcher—a fixture in their sausage-happy culture—is packing it in

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Otto-Glasbrenner-sausages-Germany-631.jpg)

When it comes to animal protein, the German language is lacking in euphemism. Meat is “flesh,” hamburger is “hacked flesh,” pork is “pig flesh” and uncured bacon is “belly flesh,” as in, “Could you please pass me another slice of flesh from the pig’s belly?”

A favorite children’s food, a bologna-like luncheon meat, is called by the curious term “flesh sausage.” No family visit to the meat counter is complete without a free slice of “flesh sausage” rolled up and handed to a smiling youngster in a stroller. Few things put me in a pensive mood like hearing my daughter cry out in delight, “Flesh, Papa! I want more Fleisch!”

While I’ve grown accustomed to the culinary bluntness of the German language after living here for a few years, I still wince at the coarseness of the cuisine itself. I find certain traditional meat dishes difficult to stomach, such as Eisbein, a boiled pig’s knuckle the size of a small meteorite served with a thick, fatty layer of rubbery skin and protruding leg bone. Or Saumagen, former Chancellor Helmut Kohl’s favorite dish, which is reminiscent of that Scottish favorite, haggis. Imagine all sorts of meats and vegetables sewn into a pig’s stomach and boiled—unless you’d rather not. Then there’s the dish known to induce cravings along the lines of the American yen for White Castle burgers. It’s called Mett, and Germans will eat it for breakfast, lunch, an afternoon snack during a hard day of labor or to satisfy a late-night longing.

Mett is finely ground raw pork sprinkled with salt and pepper, spread thickly across a split roll, or Brötchen, like an open-faced sandwich, and topped with diced onion. I could swear I’ve seen it topped with a sprinkling of fresh, minced parsley, but my wife, Erika, who is German, assures me such couldn’t be the case because that—that—would be gross. She doesn’t eat Mett often—I’ve never seen her consume it in seven years of marriage—but when the topic comes up, I’ve heard her make an uncharacteristic lip-smacking noise followed by, “Mmm, yummy, yummy.”

Consuming raw pork is hardly imaginable in America, where we typically boil precooked hot dogs “just in case” and cook our pork chops until they’re rubbery. Given its checkered history with parasites that cause trichinosis, pork is forever suspect. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends cooking pork to an internal temperature of 170 degrees; commercial kitchens are required to.

Eating raw pork requires a leap of faith we see in few countries outside of Germany, where the nation’s butcher profession has been held in high regard for more than seven centuries. Germans know they can trust the quality of their meat.

Granted, I’m a queasy eater. I prefer meat masquerading as nuggets to a platter of tongue with its paisley swirl of taste buds. But one day, in an adventurous spirit, I ordered a Mett Brötchen at a popular outdoor café nestled in the shadow of Aachen’s Kaiserdom, Charlemagne’s imperial cathedral, which he built more than 1,200 years ago. The glistening pink marbled meat looked a bit like raw packaged hamburger, but shinier and more delicate, ground to the consistency of angel-hair pasta. As I brought the meat toward my mouth, I instinctively closed my eyes, then took a bite and boldly toyed with it atop my tongue. The texture was not at all sinewy, but rather soft, almost like baby food; the flavor was decidedly savory, with a welcome tang of onion.

Later that night, flushed with pride, I related my heroic attempt at culinary assimilation to Erika and her mother as we snacked on cold cuts and buttered bread—a common German evening meal. My mother-in-law’s eyes widened as she pursed her lips. Then silence.

“You didn’t buy it directly from a butcher?” Erika finally asked.

“Well, no, but I ordered it from one of the finest cafés in town.”

She grimaced. “When you eat Mett, you don’t want there to be a middleman.”

I spent the rest of the night in bed contemplating the irreversible nature of digestion.

Although Erika and her mother will buy meat only from a butcher—and a butcher whose meat comes from a nearby farm—the majority of Germans no longer have such inhibitions. Freezers that used to be the size of shoe boxes, but were well suited to frequent visits to neighborhood butchers and markets, have been replaced with freezers big enough to hold several weeks’ worth of groceries bought at American-style supermarkets. In Germany, the shunning of local butchers amounts to the repudiation of a cultural heritage.

German butchers are fond of pointing out that, while their profession may not be as old as prostitution, it dates back at least to biblical times, when temple priests honed their slaughtering and meat-cutting skills while sacrificing animals at the altar. In recognition of this, the emblem of the German butcher profession was once the sacrificial lamb. One of the earliest historical mentions of sausage comes from Homer’s Odyssey—grilled goat stomach stuffed with blood and fat—but it is Germany, with its 1,500 varieties of Wurst, that is the world’s sausage capital.

Germans, blessed with a temperate climate and abundant pastureland, have always eaten a lot of meat, and sausage is a natural way to preserve every scrap of an animal. The frankfurter—America’s favorite sausage—was indeed invented in the city of Frankfurt in the late 15th century. (Austria lays claim to the virtually identical Wiener, which means “Viennese” in German.) Bismarck was such a fan of the sausages that he kept a bowl of them on his breakfast table. Then, as now, frankfurters were prized for their finely minced pork, dash of nutmeg and—since the 19th century—pickle-crisp bite, a tribute to sheep’s-intestine casings.

The Bratwurst, a favorite of Goethe’s, can be traced at least as far back as the 15th century, when the Bratwurst Purity Law outlawed the use of rancid, wormy or pustulated meat. These days Bratwursts are generally served at food stands, where they are mechanically sliced into medallions, smothered with a sweet, rust-colored condiment called “curry ketchup” and sprinkled with bland curry powder. When not eaten as Currywurst, a long, uncut Bratwurst is placed in a bun comically small for the task.

Currywurst is about as adventurous as German food gets, at least in terms of seasonings, which more typically consist of pickling spices and caraway seeds. For the longest time, Germans viewed foreign gastronomy with a mixture of suspicion and envy. Garlic wasn’t successfully introduced to the German palate until the 1970s, with the arrival of guest workers, and Italian and other Mediterranean foods didn’t gain in popularity until the late ‘80s. As far as embracing the legendary brilliance of French cuisine, the border between the two nations is apparently more porous to armored tanks.

In many ways, German food hasn’t changed much since the days of Tacitus, who described it as “simple.” At its core, German cuisine is comfort food (usually pork) meant to stick to one’s ribs. Eating isn’t a very sensuous affair: a meal is served all at once and not so much savored as consumed. At first I thought it was just one of my wife’s endearing quirks; then I noticed that her friends are just as likely to finish a meal before I’ve emptied my first glass of wine.

When ordering meat in a restaurant, I’ve never been asked how I’d like it done. Apparently, there is no German equivalent for “medium-rare.” More than once I’ve pulled a leathery roast crusted with creosote out of my mother-in-law’s oven, only to be asked to slice it through the middle to ensure that it’s fully cooked.

They say food opens the door to one’s heart, but it also provides entry to, and, more important, an understanding of, one’s culture. This is particularly resonant in Germany, where the post-World War II generations have actively discarded symbols of their notorious past. But while three Reichs have come and gone, German food remains stubbornly traditional. At its heart has always been the butcher.

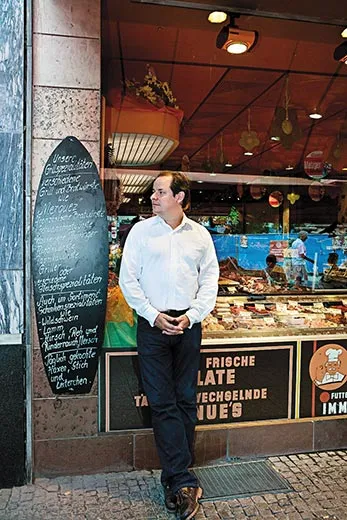

When my alarm goes off at 3 o’clock on an icy-dark winter morning, the absurdity of my rising so early begins to sink in—the last time I can remember waking at this hour was when I heard a bear rummaging outside my tent. But this is when most butchers get their work done, including Axel Schäfer, the 49-year-old, third-generation butcher down the street from our apartment in Düsseldorf, who has invited me to make sausages with him.

Axel, who has already been at work for the better part of an hour, meets me at the entrance to his family’s 80-year-old butchery dressed for action in heavy white overalls, a thick rubber apron and knee-high white rubber boots. Although he greets me with a smile, I find the thickness of the apron and the height of the boots somewhat unnerving.

Not only does Axel sense my ambivalence, he shares it: he is a recent convert to vegetarianism. Axel can’t afford to quit handling meat altogether—he has a family to support—but he has already stopped selling pâté from fattened goose livers and now offers customers an alternative to his homemade sausages: a lunch buffet for “nonjudgmental vegetarians.”

Axel stumbled across his new diet when the stress of 90-hour workweeks in a declining market frayed his nerves. A desperate visit to a nutritionist and a life coach resulted in an examination of his diet and profession, which he feels was partly foisted upon him by his family. “I felt like I was dying,” Axel says. “The pressure was killing me.”

At first, he couldn’t even bring himself to eat vegetables—too foreign—so his nutritionist recommended he try vegetable juice. “The only way I could drink it was to pretend it was soup,” Axel says. “I placed it in a jar and warmed it in the kettle with the sausages. But the more vegetables I ate, the better I felt. I no longer feel well when I eat meat.” Axel lost 45 pounds, giving him a trim appearance, even if the weight loss did accentuate his already elastic, sad-dog cheeks.

His rubber boots squeal as we step across the tiled threshold separating the front of the store from “the jungle” beyond. I expect to see employees lugging sides of beef to and fro in anticipation of the work ahead, but Axel works alone. Automation makes that possible, but there’s more to it than that.

“In my grandfather’s day, this room was packed with a dozen employees and apprentices,” Axel explains. “I only do a fraction of the business he did. Of the 40 butchers in Düsseldorf, maybe 7 make good money. Butchers go out of business all the time. I have a friend who makes more money baking gourmet dog biscuits.”

Mere decades ago, to see a butcher struggling in Germany, let alone converting to vegetarianism, would have been unthinkable. When Axel’s father contemplated medical school, Axel’s grandfather scoffed at the idea: a doctor’s income was less reliable. But industry statistics bear out Axel’s grim pronouncement. There were 70,000 butchers in Germany in the 1970s; now there are 17,000, with 300 to 400 dropping out or retiring every year.

Even if Axel could afford employees, they’d be hard to come by, given the grueling hours, physically demanding and messy work and the decline in business. Axel’s own two children have little interest in following their father’s profession. Butcher shops that were once neighborhood fixtures now simply board up their windows and close. Another demoralizing development is the increasing number of regulations from the European Union regarding meat preparation, which favor large operations.

Nor does it help that Germans are eating less red meat. Meat consumption per person has dropped 20 pounds in 20 years, to a bit more than 100 pounds, with the citizens of France, Spain and even Luxembourg now eating more meat per capita than Germans. Even though Hitler was its most famous advocate, vegetarianism continues to grow in popularity.

We arrive in a windowless white room at the far end of the building filled with several large stainless-steel machines, prep tables and the cauldron where Axel once heated his vegetable juice. One of the prep tables is crowded with bread tins filled with uncooked loaves of Fleischkäse—a goopy pink purée of meat and cheese, which, when finished, will resemble a meatloaf of sorts.

He enters a walk-in cooler and returns lugging a five-gallon steel container of the sort one finds at a dairy.

“What’s that?” I ask.

“Blood.”

Axel begins feeding ingredients into the sausage-mixing machine’s doughnut-shaped trough. First in are leftover cold cuts from the front display case. He then fishes out ten pounds of raw livers from a bag containing twice that amount and slips them into the trough. He pulls a large steaming colander filled with boiled pigskins from the kettle and pours the pale gelatinous mass (used to help bind the ingredients) into the trough. He sprinkles in a bowl of cubed lard as the machine spins and shreds its contents. Axel runs his machine at a lower, quieter speed out of deference to his neighbors, many of whom are less than thrilled to live next door to Sweeney Todd. Moments later, the mixture is a porridge the color of sun-dried tomatoes.

Axel tilts the bucket of blood into the trough until it is filled nearly to the rim. The vibrant, swirling red mass continues to churn; the aroma is earthy and sweet, like ripe compost. With a look of resignation, he adds the flavor enhancers sodium nitrate and monosodium glutamate, which quickly turn the mix a brighter red. “I tried stripping the MSG and food coloring from the sausages, but they weren’t very popular,” he says. “Claudia Schiffer without the makeup doesn’t sell.”

The mixture ready, Axel uses a pitcher, and later a squeegee, to scoop it into a white tub. “You can taste it if you’d like,” he offers, and then dips his finger in the batter and puts it in his mouth. I decline. “We sell more Blutwurst than anything else,” Axel tells me. “We’re known for it.” A favorite Düsseldorf breakfast, Himmel und Ähd (Heaven and Earth), consists of pan-fried blood sausage topped with mashed potatoes, applesauce and fried onions.

Axel unfolds 15 feet of a cow’s slippery intestinal membrane atop a prep table and then pours the sausage mixture into the funnel of a machine that pushes the mush through a tapered nozzle with the help of a foot pedal. He fills up two feet of gut at a time, twists it in the middle like a clown tying a balloon, then brings the two ends together and fastens the membrane with a heat-sealing machine, so the sausage forms a classic ring with two links. He plunks the sausage into the outsize kettle to cook. Axel works with a repetitive exactitude that borders on automated precision: pedal, squirt, twist, seal, plop. Next.

Axel ties up the last ring of sausage and tosses it into the kettle, then sets about disinfecting the kitchen with spray foam. He pauses in front of the sausage trough. “If you start thinking about it, there has been a lot of death in this machine,” he says. “Feelings like that aren’t really allowed here. If I allowed myself to turn the switch on and see everything at once, I might as well put a gun to my head. But it still pains me when I see a very small liver, because I know that it came from a baby animal.” Axel’s eyes grow red and watery. “You can say this is ridiculous—a butcher who cries at the sight of a liver.” He then paraphrases the writer Paulo Coelho’s line: “When we least expect it, life sets us a challenge to test our courage and willingness to change.”

With the last trace of blood hosed down the drain, Axel’s mood lightens. He puts on a cloth apron, reaches into the cooler and pulls out carrots, potatoes, cabbages and several packages of tofu for today’s casserole. We sharpen our knives and attack the carrots first.

“People might think it’s funny for a butcher to be vegetarian, particularly in Germany, where everything is so regimented,” he says. “But we live in the modern world and we have more options than before. For me it’s a question of tolerance. This has not been an easy transition for my wife, Dagmar, and me. We are like Hansel and Gretel holding hands in the forest.”

Axel walks back to the refrigerator and pulls out leftovers from yesterday’s vegetarian offerings: a zucchini, leek and tomato quiche. “I am teaching myself to be a vegetarian cook. It is all learning by doing.”

He hands me a spoonful of the quiche. It’s delicious.

I am whizzing toward stuttgart on a high-speed train with Gero Jentzsch, the plucky 36-year-old spokesman for the German Butchers Association. “If you look at the number of butchers leaving the profession each year, it’s like a countdown that can’t be stopped,” Gero tells me in impeccable English. “I imagine the hemorrhaging will stop when there are 8,000 to 10,000 left and the profession rediscovers its position in the marketplace. Where else are you going to go for high-quality meats and artisan sausages?”

I had spoken by phone with Gero two weeks earlier, trying to put Axel’s struggle and the rapid decline of Germany’s most iconic profession into context. “A vegetarian butcher, eh?” Gero had said. “Well, it’s an interesting business model for a challenging time. Most butchers are branching out into catering, cafés or organic products—so-called ‘green meat.’ Everyone must specialize if they want to survive. I guess selling vegetables is one way to do that. We could all use more balance in our diet, and I know plenty of overweight butchers who might benefit from eating more vegetables. But I have a feeling it means we’ve lost yet another butcher.”

To gain a better understanding of the history of the profession, Gero had recommended a visit to the German butchers museum in a village near Stuttgart. An ardent medievalist who, when he can, spends weekends in drafty castles dressed in artfully tailored period costumes, Gero speaks excitedly about the museum’s collection of ornate treasure chests, which played a prominent role at secretive and highly ritualized candlelit gatherings of the medieval butchers’ guilds.

“It’s difficult to overemphasize the critical role the master butcher has played in Germany’s cultural heritage,” he tells me. “France has its cheese and cheese makers; Germany has its sausages and sausage makers.”

Throughout our conversation, Gero draws a distinction between meat and sausage, which I had always thought of as one and the same. “Meat is meat,” Gero explains, “but sausage carries the culture.”

Sausage permeates German culture at nearly every level, much like rice in China. The German language is peppered with sausage sayings, such as Es ist mir Wurst—“It’s sausage to me.” (“It’s all the same to me.”) And while Richard Wagner worked passionately with mythical Germanic archetypes in his dramatic operas, the average German is less likely to feel a connection to Lohengrin, Siegfried or Brunhild than he is to a far more popular theatrical legend: Hans Wurst, the pants-dropping wiseacre who once dominated hundreds of German plays.

“Sausages are recipes, and these recipes reflect who we are,” Gero adds. “In the North, [people] have always been closely linked to the sea, so it’s not surprising that they eat sardine sausages.” Bavaria has always been a conservative region heavily tied to the land. They tend to eat very traditional sausages that use more parts of the animal. For example, Sülze, a jellied sausage made with pickles and flesh from a pig’s head, that has a crisp, sour taste.

“But these days tradition counts less than appearance. It’s mainly pensioners who continue to buy their sausages from the butcher rather than the supermarket, because they know the difference; younger people never learned the habit. Children today prefer sausages with smiley faces or animal designs, something no German butcher can do by artisanal means.”

Traditional butchers put a lot of care into the appearance of their sausages. Every sausage has its traditional size and shape, and butchers also make sausages with fancier designs for special occasions. Slices of tongue might be arranged into a star or clover pattern, for example, with a blood-red background of well, blood, which is then sprinkled with tiny white lard cubes, thus producing a sort of starry-night effect. But such craft today pales in popularity with mass-produced, two-toned sausages extruded and molded into animal shapes with paws and smiley faces. One favorite—“little bear sausage”—even has matching children’s books and board games.

Gero and I are picked up at the Stuttgart train station by a distinguished-looking gentleman named Hans-Peter de Longueville, who is the local representative of the butchers’ association. He drives us out of the valley and into the hills beyond, where we soon arrive in the little village of Böblingen, next door to the world headquarters of Mercedes-Benz.

An elderly docent wearing a coat and tie greets us in front of a 16th-century Tudor-style building housing the butchers museum. He shakes my hand and stands at attention, awaiting direction from Herr de Longueville. I sense my visit has ignited a degree of excitement. That anyone, let alone an American writer, would want to delve so deeply into butchering has clearly awakened a certain amount of pride. All three men possess an extensive knowledge of butchering, but few outside the industry are interested in hearing what they have to say. I’m the red meat they’ve been waiting for.

I am ushered into the first exhibit hall, which is filled with historical equipment arranged into make-believe period butcher shops, beginning with the Middle Ages and ending with the early 20th century. Apparently, early butchering gravitated toward a form of gigantism. Everything is huge: knives are swords, scales are the size of Lady Justice herself and cash registers weigh hundreds of pounds.

In front of the 19th-century display is a hefty butcher block that appears severely warped. Atop it rests a tool with three crescent-shaped blades used to mince meat with the aid of two men. The docent grabs one end and demonstrates its seesawing motion. Meat workers sang songs and danced a sort of jig while mincing, like sailors raising sails on a clipper ship. When I join the docent at the other end of the mincer, I am surprised by the weight of the tool, which explains the table’s deeply uneven surface. This is what it took to mince meat for sausage or hamburger at the start of the Industrial Revolution.

Peasants began flocking to cities a thousand years ago. Urbanization demanded specialization, which led to the formation of the four primary guilds—butchers, bakers, shoemakers and cloth-makers—and the beginnings of a bourgeoisie that would one day threaten monarchical rule. Among tradesmen, the butcher held a place of honor. Meat, the most prized of foods, is also the most difficult to handle.

Because of this level of responsibility, as well as a deep knowledge of all things sharp and deadly—butchers were known as Knochenhauer, or bone-hackers—they were granted permission to carry swords and often placed in charge of a city’s defenses. They also made frequent trips to the countryside to purchase cattle, sometimes delivering written correspondence along the way for a fee, which eventually led to the formation of Germany’s first mail service, called the Metzgerpost, or “butcher post.”

Until an 1869 law weakened the guild system, the butchers guild exercised total control over the profession—deciding, for example, who could become a butcher and what one could charge for a cut of meat or sausage. Acceptance into the guild was the medieval equivalent of becoming a made man. The profession survived the Industrial Revolution and though it has had its share of difficulties—if it took a wheelbarrow of reichsmarks to buy a loaf of bread during the Weimar Republic, imagine how many it took to buy a roast—it wasn’t until the rise of supermarkets in the early 1980s that the profession went into a tailspin.

Herr de Longueville has arranged a special lunch at the nearby Glasbrenner Butchery, featuring local sausages prepared by a master butcher. Once seated, Herr de Longueville sets the stage by explaining the three main categories of sausage: “boiled” (think hot dogs), “raw” (smoked or air-dried, like salamis) and “cooked.” The last is a bit more difficult to explain, but it’s basically a sausage containing already-cooked meats. Although I have little experience with such sausages, from what I can tell they’re the ones with names like “headcheese,” whose casings are filled with the sort of things a delicate eater like me studiously avoids.

Moments later, the butcher’s wife arrives at our table carrying a “slaughter plate”—an oversize platter brimming with cold cuts selected for my enjoyment and edification—and places it directly in front of me. Herr de Longueville, the docent and the butcher’s wife gaze at me in anticipation. Gero, who is aware of my culinary timidity, smiles hesitantly.

I don’t recognize any of the sausages. At least there’s no liverwurst, the smell of which nauseates me. I’m told that the gelatinous, speckled sausage slices before me include the following ingredients: blood, head flesh, gelatin, lard, tongue, tendon (for elasticity), skin and something that my hosts have difficulty translating. They eventually settle on “blood plasma.”

“Oh, you’ve eaten it all before—you just didn’t know it,” Gero says. “If you think about it, a steak is just a piece of a cow’s buttocks.”

The muscles around my throat begin to feel tender to the touch. “Is there any mustard?” I ask.

Once I’ve sampled each sausage, the slaughter plate is removed. Moments later, the butcher’s wife returns with another platter, filled with a dozen varieties of liverwurst. I politely wipe away the bead of sweat now forming on my upper lip.

Next comes the Maultaschen, layered dumplings particular to this region of Germany that resemble compressed lasagna, followed by cutlets of meat in a light broth.

“What’s this?” I ask.

The docent taps his jawbone. Gero explains: “Castrated ox cheeks.”

Back in Düsseldorf, my neighbors are waiting in silent anticipation for our local supermarket to reopen after a month-long remodeling. When it does, I walk over with my daughter to see what the fuss is all about. Aside from new shelving and brighter lighting, the first thing I notice is the expanded meat section. The refrigerated shelves are filled with a wider variety of mass-produced sausages, along with more traditional types, like tongue sausage, aimed at the older, butcher-loyal generations. There are organic meats and sausages in bright green packaging, as well as a line of sausages from Weight Watchers advertising “reduced fat!” There’s even nitrogen-packaged Mett with a one-week expiration date.

My daughter is attracted to the bear-shaped sausage, but I decline to buy it because we tend not to eat that sort of thing. We shop for fresh food several times a week, buying bread at the bakery, meat from the butcher and fruits and vegetables from the greengrocer or the weekend farmers market. Erika is so demanding about quality that I feel sheepish about entering a supermarket for anything other than paper products or canned goods.

There is also an expanded butcher counter and display case, where one can have meats sliced to order. Although I hardly have the stomach for more sausage after my trip south, journalistic duty compels me, so I ask for a taste of the “house salami.” It looks like a butcher’s salami, but when I bite into it, it’s greasy and bland. I ask the woman behind the counter who made it. She doesn’t know. “Can you tell me where it was made?” She can’t.

It’s a phenomenon that I’ve grown accustomed to in the United States: food that looks like food but lacks flavor. And whereas a master butcher knows exactly where his meat comes from, supermarket meat in Germany now travels from industrial farms and slaughterhouses all across Eastern Europe. Ultimately, a butcher proudly stands behind his quality; the supermarket worker may or may not take pride in his job, let alone have a master’s knowledge of it. The worker behind the meat counter could just as easily be stocking shelves.

Still, Germans by and large continue to overlook their remaining master butchers. There are now entire generations of Germans who can’t taste the difference between a handcrafted sausage and a mass-produced one.

That a squeamish foreigner should grieve for German butchers may seem odd. But for me, it’s about the loss of quality craftsmanship. Sadly, butchers aren’t getting help even locally. The city of Düsseldorf recently closed its slaughterhouse because it was deemed unseemly, opting to replace it with luxury housing. Meat is now shipped to butchers from regional suppliers.

I have little interest in buying “flesh sausage” for my daughter at the supermarket, so I walk over to Axel’s instead. It’s been a few weeks since we’ve bought meat, and to my surprise, Axel’s shop is in the midst of its own makeover. The large menagerie of life-size farm animals that graced the store’s marquee for decades is gone. A Tibetan flag hangs from one of Axel’s upstairs windows, lending the otherwise drab building the air of a college dormitory. In the entryway, framed copies of jackets for Paulo Coelho’s books line the walls, and a cup filled with brochures advertises Axel’s newest passion: shiatsu massage. The brochures feature a photo of Axel dressed in his white overalls, but minus his rubber apron and boots, applying pressure to the spine of a prone human figure.

Axel greets us from behind the meat counter, but gently guides us away from the sausages (which he no longer makes, but buys from a nearby butcher) and toward the steam tray filled with today’s vegetarian offerings: pasta with mushrooms, lentil soup, spinach quiche and a casserole with steamed veggies and smoked tofu. Axel hands my daughter a spoonful of the casserole. She likes it.

“I’m glad you like it,” he tells her with a smile. “It’s good for you.”

She points to the steam tray. “Tofu, Papa!” she demands. “I want more tofu!”

Andrew D. Blechman’s latest book, Leisureville, is about age-segregated utopian communities. Andreas Teichmann is an award-winning photographer based in Essen, Germany.