Forensic Science for Antiques

Revealing art secrets—and exposing forgeries

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/csi-631.jpg)

The clients had paid many thousands of dollars for the Chinese silk samples with the bird motifs and now wanted reassurance that they were indeed from the Warring States period (about 480–221 B.C.).

But the news was not good. After testing them, the Rafter Radiocarbon Laboratory in New Zealand declared the samples less than 50 years old. "We had some really unhappy submitters," says Dr. Christine Prior, team leader at Rafter, which is part of the National Isotope Centre of the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences.

We've all marveled at the forensic wizardry that traps villains on such TV hits as CBS's "CSI" ("Crime Scene Investigation"), but dazzling science is also exposing secrets in another, more refined field—art. Armed with the latest technology, art historians are becoming cultural detectives, piecing together the puzzle of an item's past and, in the process, helping differentiate genuine from bogus.

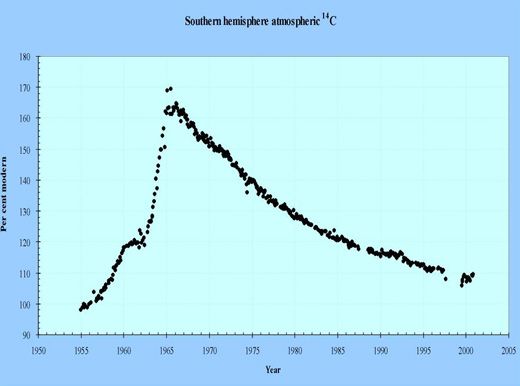

The fake Chinese silk samples fell afoul of radiocarbon dating, a technique discovered in 1949 but greatly improved since then. It can tell the age of material (such as wood, silk, cotton or bone) that was alive in the last 50,000 or so years by measuring the amount of carbon 14 it has lost. Dr. Prior says that the period 1650 to 1950 is hard to date precisely because so much fossil fuel (oil and coal) was burned that it "disturbed the natural production cycle of carbon 14." However, nuclear tests conducted in the 1950s and 1960s released huge quantities of carbon 14 in the air, creating the "bomb effect"—a chronological benchmark.

"Although art and antiquities forgers can be very exact in replicating materials, style and technique," she explains, "if they use a raw material that has been growing since 1950, it will have 'bomb' carbon 14 in it."

Radiocarbon dating and other high-tech tools have become such adjuncts to art collecting that many museums and art galleries have extensive in-house laboratories. Wondering about the age of an oak panel painting from northern Europe? Dendrochronology can reveal when the tree was felled by counting the number of rings in the wood. Trying to date an Italian bronze? X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopes detail the metal's composition, thereby providing the alloy mix that is characteristic of a certain period. And if the item is too large to bring to a lab, portable XRF machines provide in situ inspection. Could this be a newly discovered Monet? Pigment analysis will tell whether the paints used were available during Monet's lifetime. Infrared reflectography, ultraviolet light, plain old X-rays, CT scans and microscopes are all part of the exploratory process.

Nicholas Penny, the new director of the National Gallery in London and former senior curator of sculpture at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., says: "A very great deal of the investigation is undertaken to find out how an item was made, not necessarily to clear it for authentication."

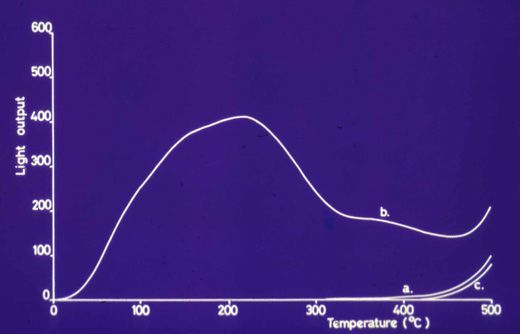

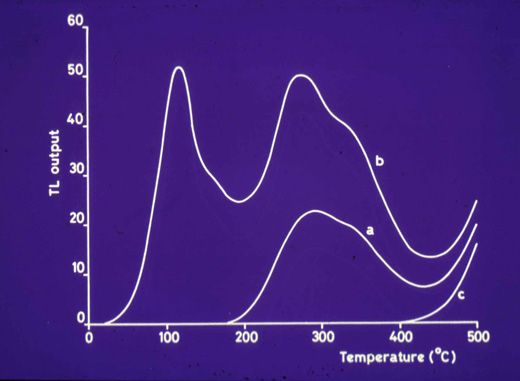

But authentication is an overwhelming issue, especially when it comes to Chinese items. Soaring auction prices—Christie's sold a Yuan Dynasty (mid-14th century) blue and white porcelain jar for $27.7 million in 2005—combined with China's tradition of reproduction have proved a dangerous mix, leading to a flood of forgeries. Almost 75 percent of the so-called antiques marketed through Hong Kong are said to be copies. That's where another state-of-the-art technique comes in: thermoluminescence (TL) dating. Small samples taken from inconspicuous parts of the object are heated to a sufficiently high temperature to produce a measurable blue light (thermoluminescence). Pottery, porcelain and the casting cores of bronzes can be dated by the amount of radiation the piece absorbs. The more intense the glow, the older the piece.

"Our conclusions are based purely on measurement and not on databases or 'expert' opinion," says physicist Doreen Stoneham, director of Britain's Oxford Authentication Ltd., which tests between 3,000 and 3,500 items a year, 90 percent of them Chinese. With a client base of almost 2,000, including the most prestigious museums and art galleries in the world, plus 50 representatives authorized to take samples in 12 countries, the laboratory is the gold standard in TL testing. Its certificates are so desirable that, ironically, they too have been victims of forgery.

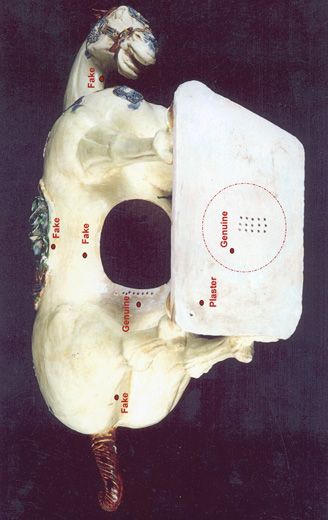

To outsmart TL, forgers artificially irradiate items, re-work old clay, mix and match parts from several objects or glaze the phony areas, forcing the test to be done on a genuine section. Oxford assures its test is plus or minus within 20 percent accurate of the date the piece was fired, but sometimes an item is fired more than once, making the dating less reliable.

"The only way to reduce the risk of deceptive results," says Dr. Stoneham, "is to use several techniques in conjunction, to examine different aspects of the object."

And don't forget that old standby—the individual.

"The human element comes in interpreting the results of the tests," says Dr. Penny. "To say that all these methods are available doesn't mean that all are being applied. Sometimes the overwhelming evidence is such that this is not needed."