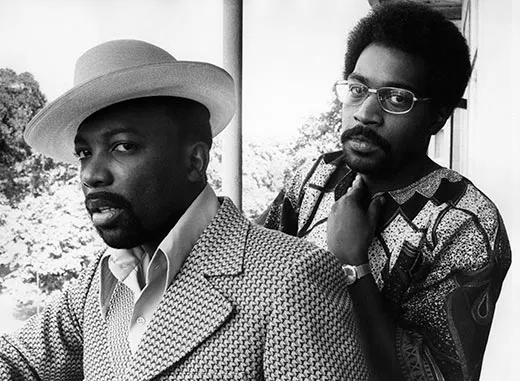

Forty Years of Philadelphia Sound

Songwriters Leon Huff and Kenneth Gamble composed tunes with political messages for chart-toppers like the O’Jays and Billy Paul

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/philadelphia-sound-the-ojays-631.jpg)

When Leon Huff and Kenneth Gamble would huddle to write songs, they’d each bring a long, yellow legal pad of potential titles, sometimes 200 or 300 each. Huff would sit at the upright piano in his office with a tape recorder rolling. He would start playing and Gamble would riff lyrics. “Sometimes [the songs] would take 15 minutes to write and sometimes they’d take all day,” Gamble recalls. “The best ones came in ten, fifteen minutes.”

The two first ran into each other in an elevator in Philadelphia’s Schubert Building, where they were working as songwriters on separate floors. Soon after, they met at Huff’s Camden, New Jersey home on a Saturday and wrote six or seven songs the first day. “It was an easy, easy fit,” Gamble recalls.

During the 60s, they had moderate success with hits like “Expressway to Your Heart” by the Soul Survivors, “Cowboys to Girls” by the Intruders and “Only the Strong Survive” by Jerry Butler.

But they wanted to be more than writers and producers of regional hits who occasionally made a national mark. The opportunity came 40 years ago in 1971 when Columbia Records, hoping to finally break into the black music market, gave them a $75,000 advance to record singles and another $25,000 for a small number of albums. With the money, Gamble and Huff opened their own label, Philadelphia International Records (PIR).

As they sat down to compose following the deal, the Vietnam War raged on, conflicts over desegregation spread across the country and civil war ravaged Pakistan. “We were talking about the world and why people really can’t work together. All this confusion going on in the world,” Gamble says. “So we were talking about how you need something to bring people together.”

One of the titles on a legal pad had promise: “Love Train.” Huff fingered the piano. Gamble, the words guy, began singing, “People all over the world, join hands, form a love train.”

Within 15 minutes, he recalls, they had a song for the O’Jays, a group from Canton, Ohio, that had considered calling it quits after a couple of minor chart successes. Gamble and Huff had spotted them three years earlier opening a show at Harlem’s Apollo Theater. While Eddie Levert had been singing lead for the trio, they liked the interplay between Levert and Walter Williams they saw onstage. So for the first singles on PIR, they wrote songs featuring the two trading vocals. “I knew once we put our leads on Back Stabbers it had the potential to be something special, but I didn’t know to what magnitude,” Williams says.

“Love Train” was the third single released from their album Back Stabbers, issued in August 1972. By January 1973, the song was number one on the Pop and R&B charts and on the way to selling a million singles, just the kind of crossover hit Columbia envisioned when it invested in Gamble and Huff.

A little more than a year after forming PIR, they also had produced hits with Billy Paul’s “Me and Mrs. Jones,” the Spinners’ “I’ll Be Around” and Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes’ “If You Don’t Know Me By Now.” Clive Davis, then chief operating officer of Columbia, wrote in his memoir that Gamble and Huff sold ten million singles. Just as important, they were Columbia’s foray into the market for albums by black artists. Back Stabbers sold more than 700,000 copies that first year.

They’d created the Sound of Philadelphia. The City of Brotherly Love joined Detroit, the home of Motown, and Memphis, the home of Stax Records, as sanctuaries of soul.

Their sound bridged sixties soul and the arrival of funk and disco. Gamble once said someone told him they’d “put the bow tie on funk.” During the 1970s, they arguably dethroned Motown as the kings of R&B, selling millions of records, and in 2005, they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

“They found a way to marry the Motown machine with the Stax grit,” says Mark Anthony Neal, a professor of African and African-American Studies at Duke University. “So you get this sound on one level that is glossy and smooth, but at the same time it kind of burns the way we think about Stax.”

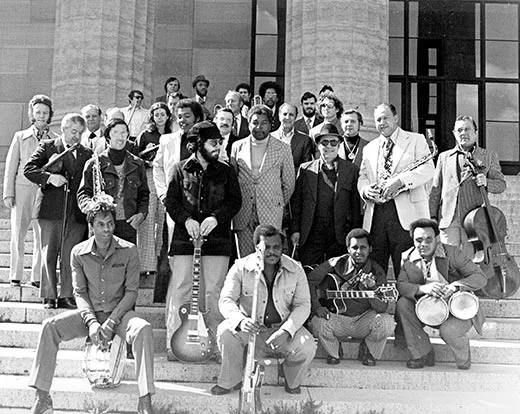

Gamble admired Motown, which he calls “the greatest record company that’s ever been in the business.” He and Huff set up a house studio band, MFSB (Mother, Father, Sister, Brother), like Motown’s Funk Brothers. The band featured the rhythm section from the Romeos, a band Huff, Gamble and producer and writer Thom Bell played with on weekends, a group of horns they saw playing a local theater, and a string section composed of retirees from the Philadelphia Orchestra. MFSB’s palette was broader, more ambitious. Mono sound and a focus on hit singles had given way to stereo and the album format. “Stereo was worlds away,” Gamble says. “The music sounds so much better.”

They found seasoned artists and transformed them into national acts. The O’Jays had been around for a decade. Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes had been singing for 15 years. Billy Paul was a star only in the Philadelphia-New York corridor. “They knew how to package certain kinds of artists in certain ways,” Neal says. “One of their really big early hits was Billy Paul’s ‘Me and Mrs. Jones.’ What’s more mainstream than a tale about infidelity?”

Like Berry Gordy at Motown, Gamble and Huff set up competing teams of writers. Walter Williams of the O’Jays recalls going to Philadelphia to record (two albums per year in those days) and listening to 40 or 50 songs auditioning for an album. They’d narrow them to 15 or 20 to rehearse extensively and cut in the studio, and then 8, 9 or 10 would make the record.

How involved were Gamble and Huff? “Like they might have been the fourth and fifth member of the group,” Williams recalls. “If Kenny wanted it sung a certain way, he would actually sing it for you. I would always try to outdo him. I’d sing it better and put more into it.”

There was a formula to the albums, Gamble says. “We would pick three or four songs with social messages and three or four songs that were nothing but dance, party songs, then we’d have three or four that were lush ballads, love songs. We tried to write songs that people would relate to for years to come.”

While the business model was based on Motown, the message was different. “This is a black-owned company, but unlike Motown this is a black-owned company that is going to put its politics into the music,” Neal says.

The songs had titles like “For the Love of Money,” “Only the Strong Survive,” “Am I Black Enough for You,” “Wake Up Everybody” and “Love Is the Message.” Neal is partial to “Be for Real,” a Harold Melvin cut that opens with singer Teddy Pendergrass lecturing a girlfriend about her desire for empty possessions. Gamble likes “Ship Ahoy,” a tune about African captives being transported during the slave trade that opens with the sound of whips cracking. Neal says PIR’s songs and artists endure because Gamble and Huff focused on making timeless music, not just making money.

“You cannot explain how you write a song,” Gamble says. “It comes from within your soul. You just pour out your feelings, whether it’s something you personally have gone through or a friend of yours has gone through or someone you didn’t even know.”

The duo still occasionally gets together to write. And advertisers keep knocking to use their songs, as exemplified by the ubiquitous Coors Light spots using “Love Train”. Hip-hop artists are fond of sampling PIR tunes, keeping the royalties flowing. (Sony Legacy and PIR released a four-disc boxed set, Love Train: The Sound of Philadelphia in 2008).

Gamble notes there’s still conflict raging in some of the countries listed in “Love Train” nearly 40 years ago. “I think it’s even more relevant today than it was then,” he says. “Those songs turned out to be anthems. We were talking about our feelings, but evidently they were the feelings of millions of people all over the world.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)