Found: Letters from the Hindenburg

A new addition to the Smithsonian collections tells a new story about the legendary disaster

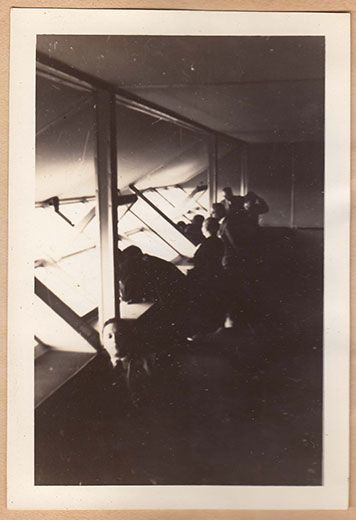

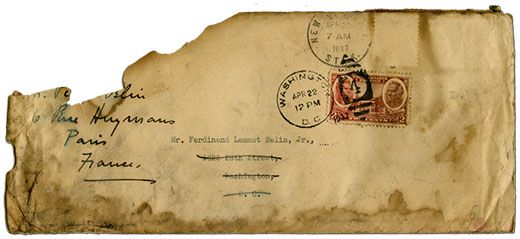

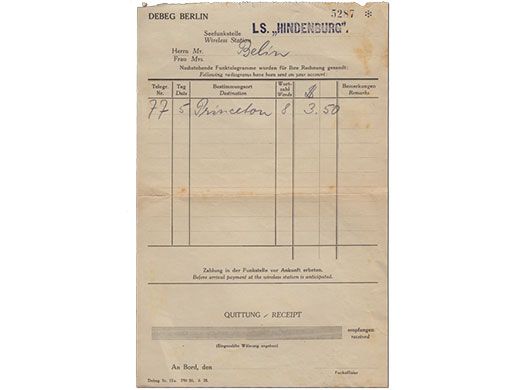

Every ounce counted onboard the Hindenburg, the 804-foot airship designed to fly across the Atlantic. The metal girders were perforated, and the piano was made of aluminum. Each passenger was assigned a single napkin to reuse in the luxurious dining hall. And yet the hydrogen-filled zeppelin was hauling hundreds of pounds of mail when, for reasons that are still unknown, it burst into flames on May 6, 1937, above a New Jersey field, killing 35 of 97 riders. Transcontinental mail was indispensable cargo; despite the year-old vessel’s glamorous image (tickets cost a whopping $450), the airship covered much of its operating costs by providing the first regular trans-Atlantic airmail service.

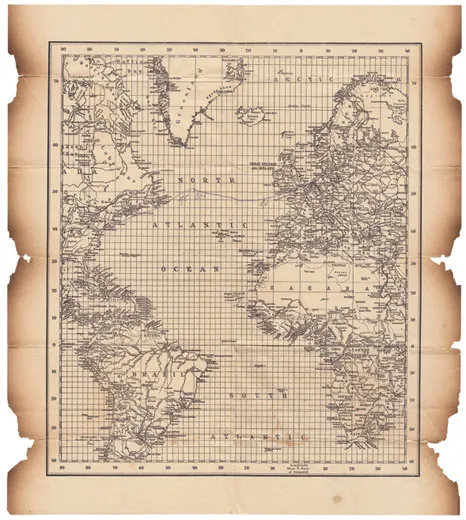

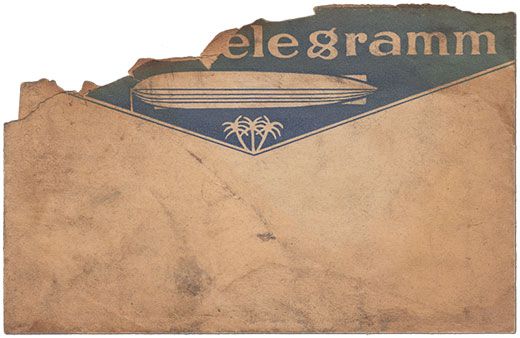

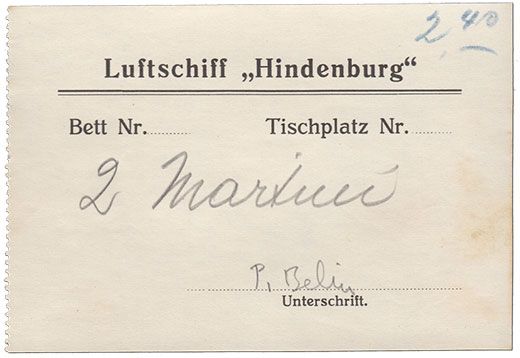

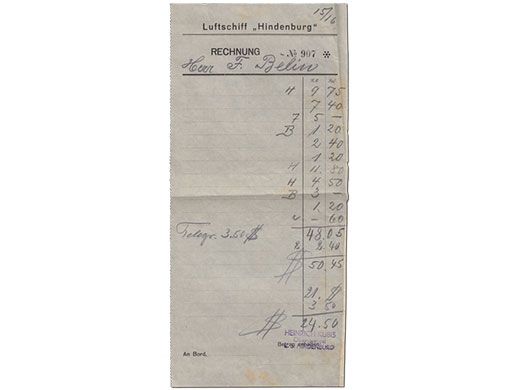

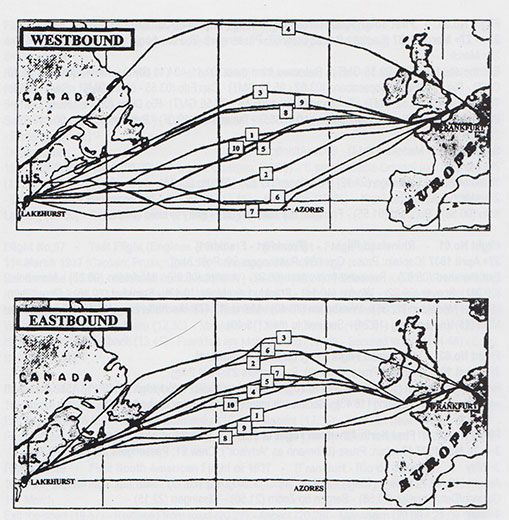

The human stories tucked in with the mailbags have always fascinated Cheryl Ganz, a leading Hindenburg historian and co-curator of a new exhibition at the National Postal Museum. In addition to many letters and postcards, the exhibit includes other frail bits of paper that survived the inferno, some of which have never been displayed before, such as a receipt for two in-flight martinis. There’s also a reproduction of the only known final flight map, which has the route from Frankfurt, Germany, to Lakehurst, New Jersey, painstakingly traced in pencil.

“We are bringing together these artifacts, these salvaged items, many of them reunited for the first time since they were picked out of the wreckage,” Ganz says. “We can piece together bits of the story that have never been told.”

The Hindenburg is one of two doomed vessels at the heart of the Postal Museum exhibition “Fire & Ice: Hindenburg and Titanic,” which marks the disasters’ 75th and 100th anniversaries, respectively. The RMS Titanic was, after all, a Royal Mail Ship, the largest floating post office of its day. When it began to founder on the night of April 14, 1912, the postal clerks made a heroic effort to drag mailbags to higher decks. The exhibit includes a set of mailroom keys and a watch recovered from their bodies. (No paper mail survived the sinking.)

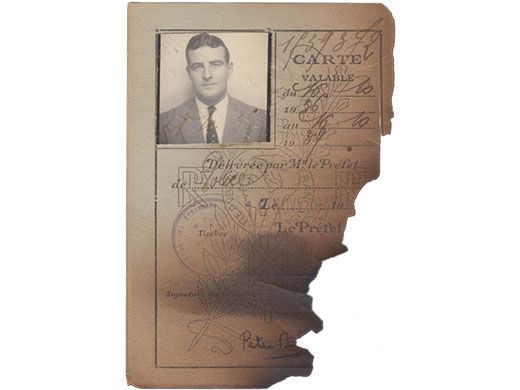

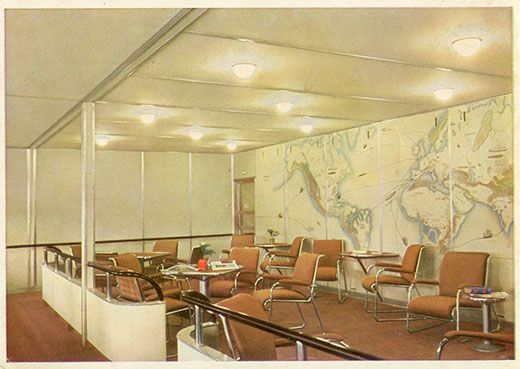

In a postal sense, zeppelins were intended to replace the Titanic-era ocean liners, which took close to a week to deliver trans-Atlantic letters. The Hindenburg made the trip in just two and a half days, and even in the teeth of the Great Depression, bankers were willing to pay extra to get deals done faster. In addition, letter-writing was a key leisure activity for passengers, who didn't have many other ways of passing the time. (Another option was smoking in a pressurized lounge, where the bartender kept the only lighter allowed on the highly flammable vessel.) The airship’s stewards sold Hindenburg stationery, postcards and stamps, which passengers used to impress their friends back home. Burtis Dolan, a Chicago perfume executive, had assured his wife that he would not fly during his trip to Europe, but he was homebound on the Hindenburg, hoping to surprise her for Mother’s Day. “I know I promised not to fly on this trip,” he wrote from the belly of the zeppelin, “but this was an opportunity I had to take.” He perished in the accident.

Of the 17,000-odd pieces of Hindenburg correspondence, roughly 360 withstood the flames, which rose 1,000 feet. Some postcards and envelopes had been placed in a protective bag for later delivery, and others were crammed in the center of regular mailbags, where oxygen couldn’t reach. These singed letters, six of them featured in the show, are among the grandest prizes of philately.

In the days after the disaster, scorched remains of letters were pieced together and sent on. Dolan’s family and friends received several notes that he’d written onboard. (A card to a neighbor is featured in the show.) The zeppelin company also had lists of some of the intended recipients of the incinerated mail. The Hindenburg’s postmaster, who had leapt to safety from an airship window, dutifully informed them via form letter that their mail would not be delivered.