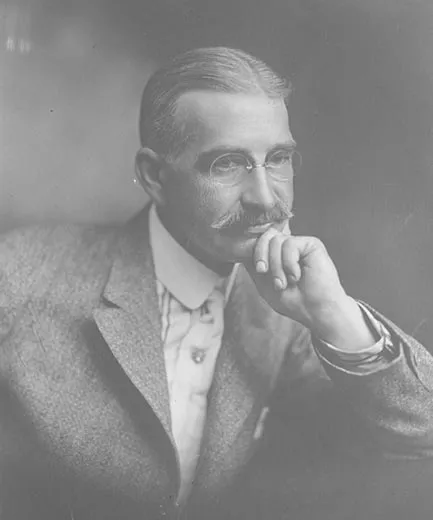

Frank Baum, the Man Behind the Curtain

The author of The Wizard of Oz, L. Frank Baum, traveled many paths before he found his Yellow Brick Road

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Wizard-of-Oz-Yellow-Brick-Road-Baum-631.jpg)

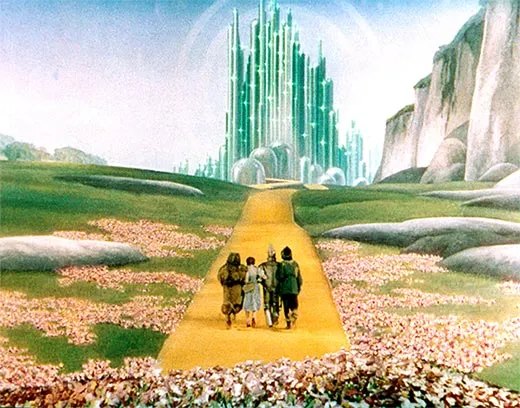

When the National Museum of American History reopened last fall after an extensive renovation, ruby slippers danced up and down the National Mall. Posters displaying a holographic image of the sequined shoes from the 1939 MGM film The Wizard of Oz beckoned visitors into the redesigned repository. In its attempt to draw crowds, the museum didn’t underestimate the footwear’s appeal. When an alternate pair of the famous slippers went on the market in 2000, they sold for $600,000.

Today, images and phrases from The Wizard of Oz are so pervasive, so unparalleled in their ability to trigger personal memories and musings, that it’s hard to conceive of The Wizard of Oz as the product of one man’s imagination. Reflecting on all the things that Oz introduced—the Yellow Brick Road, winged monkeys, Munchkins—can be like facing a list of words that Shakespeare invented. It seems incredible that one man injected all these concepts into our cultural consciousness. Wouldn’t we all be forever lost without “there’s no place like home,” the mantra that turns everything right side up and returns life to normalcy?

But the icons and the images did originate with one man, Lyman Frank Baum, who is the subject of a new book, Finding Oz: How L. Frank Baum Discovered the Great American Story by Evan I. Schwartz (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).

Born in 1856, Frank Baum (as he was called) grew up in the "Burned-Over District" of New York state, amid the myriad spiritual movements rippling through late-19th-century society. As Schwartz details in his comprehensive and entertaining book, Baum was sent to Peekskill Military Academy at age 12, where his daydreamer spirit suffered under the academy’s harsh discipline. At 14, in the middle of a caning, Baum clutched his chest and collapsed, seemingly suffering a heart attack. That was the end of his tenure in Peekskill, and although he attended a high school in Syracuse, he never graduated and disdained higher education. “You see, in this country there are a number of youths who do not like to work, and the college is an excellent place for them,” he said.

Baum did not mind work, but he stumbled through a number of failed enterprises before finding a career that suited him. In his 20s, he raised chickens, wrote plays, ran a theater company, and started a business that produced oil-based lubricants. Baum was a natural entertainer, and so his stint as a playwright and actor brought him the greatest satisfaction out of these early employments, but the work was not steady, and the lifestyle disruptive.

By 1882, Baum had reason to desire a more settled life. He had married Maud Gage, a student at Cornell, the roommate of his cousin and the daughter of famous women’s rights campaigner Matilda Josyln Gage. When Baum’s aunt introduced Maud to Frank, she told him that he would love her. Upon first sight, Baum declared, “Consider yourself loved, Miss Gage.” Frank proposed a few months later, and despite her mother’s objections, Maud accepted.

Maud was to be Baum’s greatest ally, his “good friend and comrade,” according to the dedication of Oz, but life in the Baum household was not always peaceful. On one occasion, Maud threw a fit over a box of doughnuts that Frank brought home without consulting her. She was the one who decided what food entered the house. If he was going to buy frivolous things, he would have to make sure that they did not go to waste. By the fourth day, unable to face the moldy confections, Baum buried them in the backyard. Maud promptly dug them up and presented them to her husband. He promised that he would never again buy food without consulting her and was spared from having to eat the dirt-covered pastries.

On a trip to visit his brother-in-law in South Dakota, Frank decided that real opportunity lay in the wind-swept, barren landscape of the Midwest. He moved his family to Aberdeen and started upon a new series of careers that would just barely keep the Baum family—there were several sons by this time—out of poverty. Over the next ten years, Frank would run a bazaar, start a baseball club, report for a frontier newspaper and buy dishware for a department store. At age 40, Frank finally threw himself into writing. In the spring of 1898, on scraps of ragged paper, the story of The Wizard of Oz took shape. When he was done with the manuscript, he framed the well-worn pencil stub he had used to write the story, anticipating that it had produced something great.

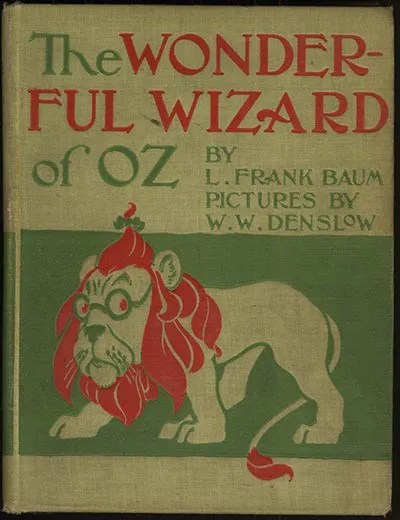

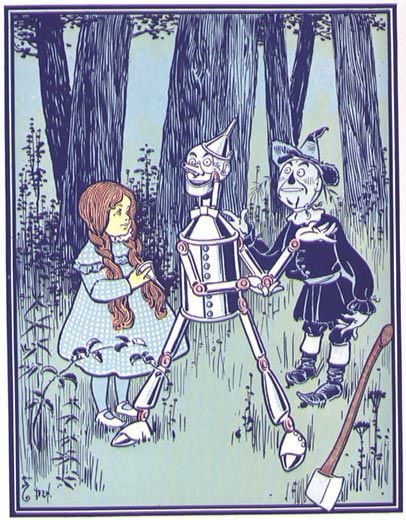

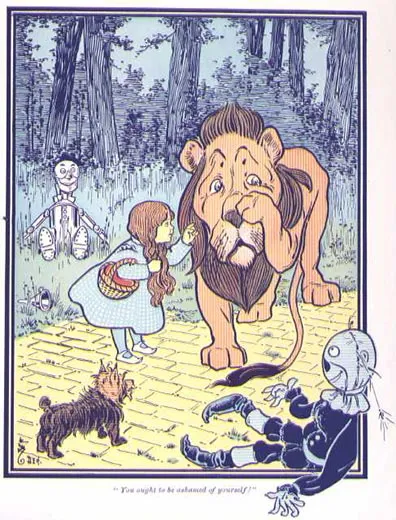

When The Wizard of Oz was published in 1900 with illustrations by the Chicago-based artist William Wallace Denslow, Baum became not only the best-selling children’s book author in the country, but also the founder of a genre. Until this point, American children read European literature; there had never been a successful American children’s book author. Unlike other books for children, The Wizard of Oz was pleasingly informal; characters were defined by their actions rather than authorial discourse; and morality was a subtext rather than a juggernaut rolling through the text. The New York Times wrote that children would be “pleased with dashes of color and something new in the place of the old, familiar, and winged fairies of Grimm and Anderson.”

But the book was much more than a fairy tale unshackled from moralistic imperatives and tired fantastical creatures. With his skepticism toward God—or men posing as gods--Baum affirmed the idea of human fallibility, but also the idea of human divinity. The Wizard may be a huckster—a short bald man born in Omaha rather than an all-powerful being—but meek and mild Dorothy, also a mere mortal, has the power within herself to carry out her desires. The story, says Schwartz, is less a “coming-of-age story … and more a transformation of consciousness story.” With The Wizard of Oz, the power of self-reliance was colorfully illustrated.

It seems appropriate that a story with such mythical dimensions has inspired its own legends—the most enduring, perhaps, being that The Wizard of Oz was a parable for populism. In the 1960s, searching for a way to engage his students, a high-school teacher named Harry Littlefield, connected The Wizard of Oz to the late-19th-century political movement, with the Yellow Brick Road representing the gold standard—a false path to prosperity—and the book's silver slippers standing in for the introduction of silver—an alternate means to the desired destination. Years later, Littlefield would admit that he devised the theory to teach his students, and that there was no evidence that Baum was a populist, but the theory still sticks.

The real-world impact of The Wizard of Oz, however, seems even more fantastical than the rumors that have grown up around the book and the film. None of the 124 little people who were recruited for the film committed suicide, as is sometimes rumored, but many of them were brought over from Eastern Europe and paid less per week than the dog actor who played Toto. Denslow, the illustrator of the first edition, used his royalties to purchase a piece of land off the coast of Bermuda and declare himself king. Perhaps intoxicated by the success of his franchise, Baum declared, upon first seeing his grandchild, that the name Ozma suited her much better than her given name, Frances, and her name was changed. (Ozma subsequently named her daughter Dorothy.) Today, there are dozens of events and organizations devoted to sustaining the everlasting emerald glow: a “Wonderful Weekend of Oz” that takes place in upstate New York, an “Oz-stravaganza” in Baum’s birthplace and an International Wizards of Oz club that monitors all things Munchkin, Gillikin, Winkie and Quadling related.

More than 100 years after its publication, 70 years after its debut on the big screen and 13 book sequels later, Oz endures. “It’s interesting to note,” wrote the journalist Jack Snow of Oz, “that the first word ever written in the very first Oz book was ‘Dorothy.’ The last word of the book is ‘again.’ And that is what young readers have said ever since those two words were written: ‘We want to read about Dorothy again.’”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)