Frank Lloyd Wright Credited Japan for His All-American Aesthetic

The famed architect was inspired by drawings and works from the Asian nation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/42/4f429201-6a3c-4ede-8910-05327eb778fb/file-20170605-16888-1nx3slh.jpg)

To mark Frank Lloyd Wright’s 150th birthday, many will pay tribute to the architect’s unique gifts and contributions to the field.

But Wright also had a rare nonarchitectural passion that set him apart from his mentor, Louis Sullivan, and his peers: Japanese art. Wright first became interested in his early 20s, and within a decade, he was an internationally known collector of Japanese woodblock prints.

It was an unusual turn of events for a young college dropout from rural Wisconsin. Because Wright was never actually formally trained as an architect, the inspiration he found in Japanese art and design arguably changed the trajectory of his career – and, with it, modern American architecture.

Space over substance

It might all have been very different had it not been for a personal connection. In 1885, the 18-year-old Wright met the architect Joseph Silsbee, who was building a chapel for Wright’s uncle in Helena Valley, Wisconsin. The following spring, Wright went to work for Silsbee’s firm in Chicago.

Silsbee’s cousin, Ernest Fenollosa, happened to be the world’s leading Western expert on Japanese art at the time. A Harvard-educated philosopher, he had traveled to Japan in 1878 to teach Western thought to the country’s future leaders. While there, he became enchanted by traditional Japanese art, and returned to the United States in 1890 to become the first curator of Japanese art at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

At the time, Japanese art was not widely appreciated in the U.S. So on his return to America in 1890, Fenollosa embarked on a campaign to convince his countrymen of its unique ability to express formal ideas, rather than realistically representing subjects.

For Fenollosa, the peculiar visual appeal of Japanese art was due to an aesthetic quality that he described as “organic wholeness” – a sense of visual wholeness created by the interdependence of each contributing part.

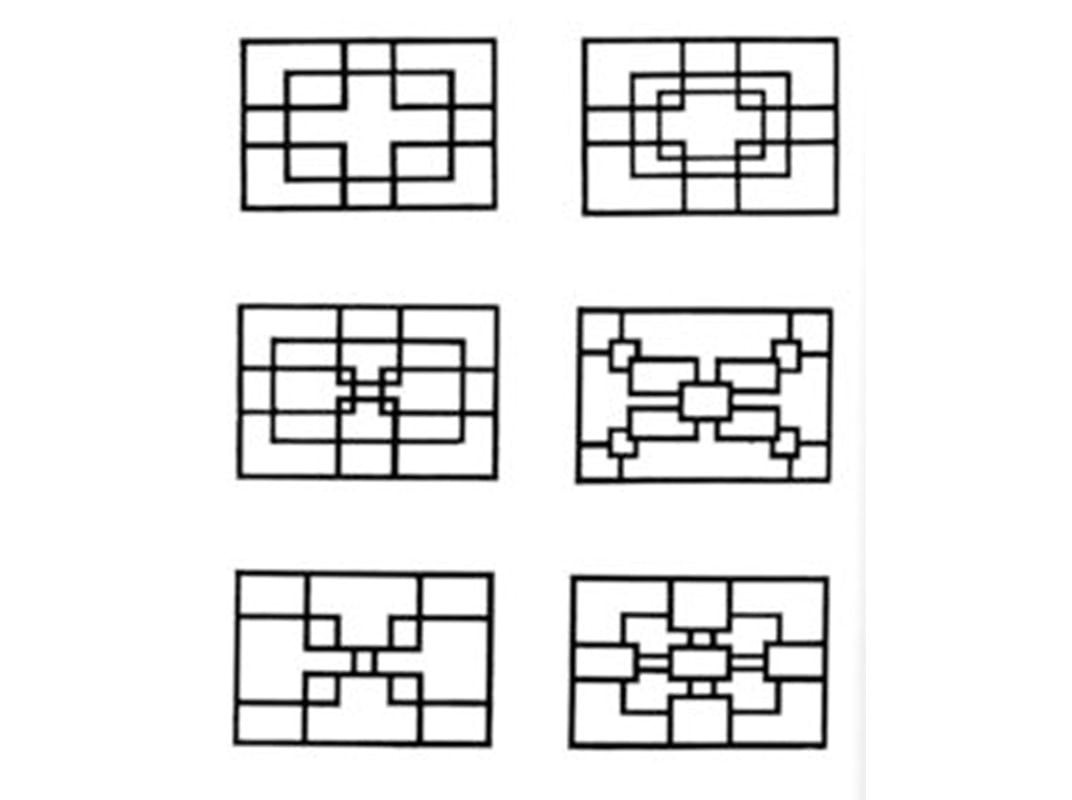

In 1899, Arthur Dow, Fenollosa’s friend and one-time assistant at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, published Fenollosa’s theory of organic wholeness in his book “Composition.” Dow applied this idea to all of the visual arts, which, in his view, were primarily concerned with the aesthetic division of space. The content of the image mattered little.

“The picture, the plan, and the pattern are alike in the sense that each is a group of synthetically related spaces,” Dow wrote. He illustrated this idea with examples of abstract interlocking patterns, which he described as “organic line-ideas.”

‘Intoxicating’ prints inspire Wright

It’s unclear whether the young Frank Lloyd Wright ever met Fenollosa in person. But we do know that Wright admired his views, and seems to have obtained his first Japanese woodblock prints from him.

In 1917, Wright recalled:

“When I first saw a fine print about twenty five years ago it was an intoxicating thing. At that time Ernest Fenollosa was doing his best to persuade the Japanese people not to wantonly destroy their works of art…. Fenollosa, the American, did more than anyone else to stem the tide of this folly. On one of his journeys home he brought many beautiful prints, those I made mine were the narrow tall decorative form hashirakake…”

Produced by pressing a dozen or more carved, differently colored cherry-wood blocks onto a single sheet of paper, the prints were considered a lowbrow popular art form in Japan. But they had been “discovered” by avant garde European artists in the 1870s, and this sparked a craze known as Japonisme that eventually reached the United States a few years later.

Wright, like Fenollosa, felt that “the Japanese print is an organic thing,” and his 1912 book on the subject, “The Japanese Print: An Interpretation,” was really a general treatise on aesthetics based largely on Fenollosa’s ideas.

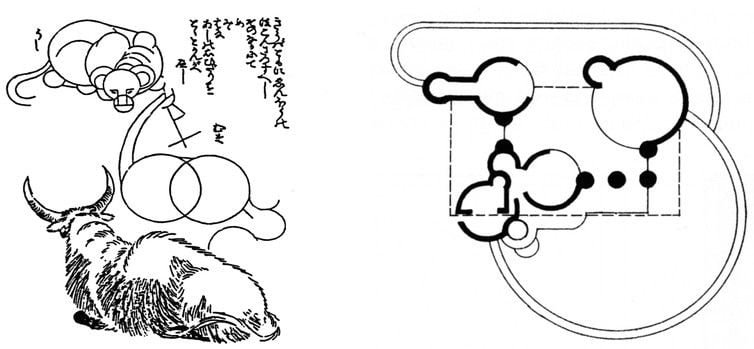

Wright’s favorite Japanese print artist, Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), had published sketches illustrating how the subtleties of living forms could be constructed from simple mechanical shapes, and Wright based his own “organic” architectural plans on similarly overlapping geometric modules – a radical notion at a time when planning was typically based on axes and grids.

In some of his prints, Hokusai would allow objects to break through their surrounding frame. Wright, similarly, allowed elements to breach the frame of his architectural drawings, as he did in his rendering of the Huntington Hartford Play Resort project.

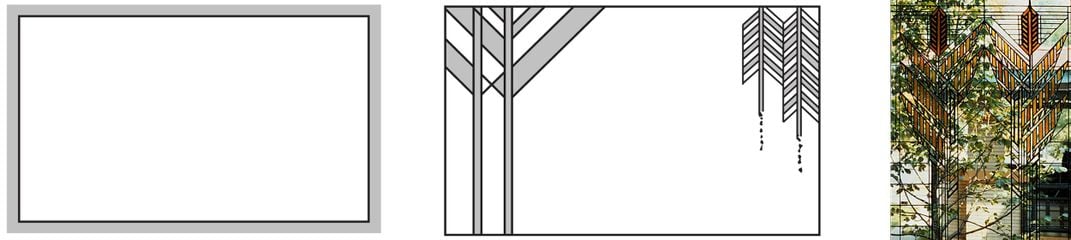

The influence of the Japanese print on Wright wasn’t limited to plans. Another of his favorite woodblock print artists, Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858), often employed foreground vegetation to frame the main subjects of his prints. Wright used the same device in many of his perspective renderings of his own buildings.

Wright took a similar approach when framing the abstractly patterned “art glass” windows he designed for many of his houses. Unlike conventional plain glass windows, Wright installed patterns over the glass, reducing the distinction between the external view through the window and the surrounding frame. The goal was to blur the normal hard line between interior and exterior space, and to suggest the continuity of buildings and nature.

This breaking of the three-dimensional frame gave Wright the means of creating an architecture that was visibly integrated with nature. The goal of unifying the built and the natural had been shared, but never fully realized, by Wright’s mentor Louis Sullivan. In works such as Fallingwater, Wright made it a reality.

Shattering the mold

In all of these examples, we see a direct link between the Japanese woodblock print artists’ breaking of the conventional two-dimensional picture frame and Wright’s famous “destruction” of the conventional architectural “box.”

Wright’s ultimate goal was to demonstrate the interdependence of the architectural “organism” with its environment, and the Japanese print provided him with the means of achieving this in his buildings. He made no secret of the directly architectural debt he owed to the prints.

“The print,” he declared, “is more autobiographical than may be imagined. If Japanese prints were to be deducted from my education, I don’t know what direction the whole might have taken.”

Without Ernest Fenollosa’s insights, however, the Japanese print might well have remained a beautiful enigma for Wright. And without a chance meeting with his cousin Joseph Silsbee, there might never have been any prints at all in Wright’s career.

Happenstance, it seems, can change lives, and even entire cultures.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Kevin Nute is a professor of architecture, University of Oregon