From Castro to Warhol to Mother Teresa, He Photographed Them All

Yousuf Karsh took a singular approach to fame and the famous

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/karsh_dec08_631.jpg)

Photography fans know him as the man who shot Winston Churchill—shot him in 1941 in a back room at the Canadian Parliament, having plucked the great man's cigar from his mouth and been rewarded with a glower that made the cover of Life magazine. Said to be one of the most widely reproduced images in history, the portrait Yousuf Karsh made that day has also graced the postage stamps of seven countries. "You can even make a roaring lion stand still to be photographed," the statesman declared, whereupon he magnanimously permitted a second click of the shutter. The alternate take, long known only to the Churchill family, shows a twinkle in the lion's eye and the hint of a smile. Side by side, the images look as disconcertingly alike and unalike as Goya's Maja Desnuda, a nude on a couch, and his Maja Vestida, same couch, same pose, same woman, dressed.

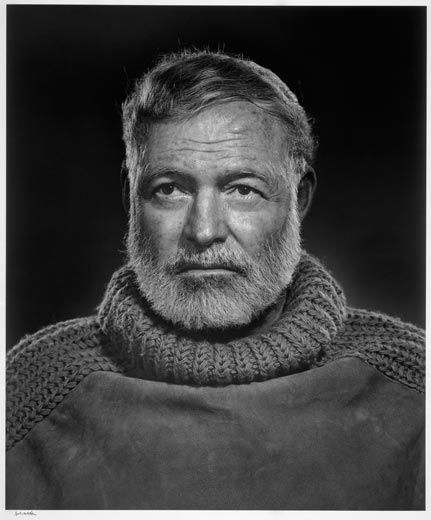

Karsh took pictures for the ages. "How," he once asked an interviewer, "can you possibly photograph an Einstein or a Helen Keller, or Eleanor Roosevelt, a Hemingway or a Churchill, and not realize they are already part of history? If your photograph is the summation of these people's many accomplishments, besides showing their human side, then the historical point of view is fulfilled." And how might one image achieve all that?

By the time he died, in 2002 at the age of 93, Karsh was well known for having shot the better known. Once he had immortalized Churchill, getting "Karshed" became as requisite a perk of fame as an entry in Who's Who, for Mother Teresa no less than for a saintly George Bernard Shaw, the ravishing young Princess Elizabeth, a rascally Robert Frost, the cigarette-smoking André Malraux or Grace Kelly in profile. This year, to mark the centennial of Karsh's birth, leading institutions from coast to coast have mounted tributes. "Karsh 100: A Biography in Images" is on view through January 19 at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the city where the photographer began his career.

Although its early chapters were shaped by terrors, his was largely a happy story. Born in Armenia in December 1908, Karsh landed in Halifax, Nova Scotia, by way of Beirut on New Year's Eve, 1925, sponsored by George Nakash of Sherbrooke, Quebec, an uncle he had never met. The atrocities and deprivations Karsh had suffered back home had not snuffed out his innate joie de vivre, and in time he would reunite his family in the New World. But first, there was the matter of carving out a livelihood. Nakash, a photographer, sent his nephew to Boston to apprentice with John H. Garo, a fellow Armenian in whose fashionable photo studio Brahmins mingled easily with artists. Garo gave Karsh a thorough grounding in the craft and art of studio portraiture, acquainted him with the works of Rembrandt and Velázquez, and included him in his social circle. "During those days of Prohibition," Karsh recalled in an autobiographical essay, "my extracurricular duties included acting as bartender for the hospitality that flowed, delivered to the studio in innocent-looking paint cans."

Under Garo, Karsh developed a lifelong addiction to the company of the great and glamorous. "Even as a young man," he said, "I was aware that these glorious afternoons and evenings in Garo's salon were my university. There I set my heart on photographing those men and women who leave their mark on the world." The studio Karsh opened in Ottawa in 1932 remained his professional address for six decades, but as he came into his own, his assignments and his passion turned him into a road warrior. "Any room in the world where I could set up my portable lights and camera—from Buckingham Palace to a Zulu kraal, from miniature Zen Buddhist temples in Japan to the splendid Renaissance chambers of the Vatican—would become my studio," he wrote. A single page of the memorial volume Karsh: A Biography in Images, captures our hero, incurably star-struck, in shots with Pope John Paul II and Jim Henson, creator of the Muppets, who are represented by Kermit.

In later life, Karsh took to publishing his albums with captions, brief or extensive, suggesting that each likeness was the record of some deep meeting of minds, whether it lasted half a minute or several days. He shot Al Hirschfeld, the theatrical caricaturist, and Hirschfeld drew him. But most of his great subjects saw him as a professional, not as a peer. "Unfortunately, I have no memory of the session," one subject of the late collection American Legends: Photographs and Commentary told me recently. "Or, to be more accurate, nothing memorable happened. Sorry."

The curator Jerry Fielder has written that Karsh "looked for, and found, the best in people," and that he "searched for the truth." But is the best the truth? Karsh shot Fidel Castro, with whom he swilled rum and Coke and swapped tales of Papa Hemingway. He shot the war criminal Alfred Krupp in a forgiving close-up. He tried in vain to shoot Stalin. Given the chance, he once told an interviewer, he would have photographed Hitler and Mussolini. He showed Charles Schulz grinning confidently at his drawing board, though the world now understands that the cartoonist's art had its roots in lifelong feelings of inadequacy and depression.

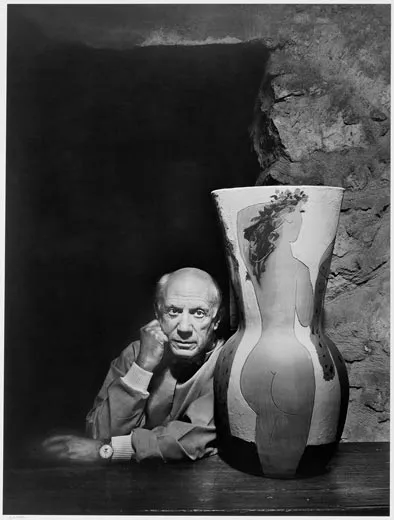

How does Karsh's work stand up? Critics have praised and mocked his mannerist obsession with sculpturally posed hands. (He liked props, too, and could use them well: a clear drafting triangle for Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a miniature Rodin Thinker for Bill Clinton.) But today's connoisseurs are apt to exclude Karsh from the company of such mandarins as Richard Avedon, Irving Penn and Arnold Newman. Karsh held a reported 15,312 sittings during the life of his studio. For every Walt Disney or Carl Jung or Madame Chiang Kai-shek, there were hundreds of mere paying customers: college graduates, brides and bridegrooms, or corporate executives dropping in for the name-brand official portrait, expecting the ceremonial old master lighting and monumental poise that were Karsh's bread and butter.

If the object of serious portraiture is to lift the mask, Karsh seldom pulls it off. He excelled at hagiography and left psychological penetration mostly in the eye of the beholder. But taken in bulk, the likenesses of his men and women who left their mark on the world add up to the record of a life richly lived—his own. As autobiography, though never intended as such, they are most revealing.

Matthew Gurewitsch is an essayist and cultural critic based in New York City.