From D.W. Griffith to the Grapes of Wrath, How Hollywood Portrayed the Poor

In the era before the Great Depression and ever since, the film industry has taken a variety of views on the lower classes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111104112023Cops-buster-keaton.jpg)

The lag between current events and their appearance in films is hard to explain at times. It’s been almost three years since Bernard Madoff was arrested, for example, and Hollywood is just getting around to criticizing him in the amiable but toothless Tower Heist. Movies that dealt with the 2008 economic collapse—like Company Men and the more recent Margin Call—felt outdated when they were released, no matter how good their intentions.

The film industry isn’t opposed to tackling social issues as long as a consensus has formed around them. Movies have always defended orphans, for example, and can be counted upon to condemn crimes like murder and theft. (In fact, a Production Code put into effect in the late 1920s ordered filmmakers to do so.) From the early days of cinema, the rich have always been a reliable target, even though the message within individual titles might be mixed. Filmmakers like Cecil B. DeMille and studios like MGM loved detailing how luxuriously the wealthy lived before showing that they were just as unhappy as the poor. And in some films, like Erich von Stroheim’s Greed (1924), the poor were vicious and cruel.

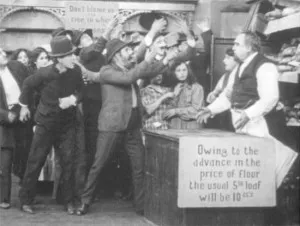

Like Greed, D.W. Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat (1909) was adapted from works by Frank Norris, a San Francisco-based writer who died before completing a trilogy of novels about American business. A Corner in Wheat attempted to show how a greedy businessman inflicted starvation on the poor, but worked better as sort of moving picture version of a political cartoon. Other filmmakers followed Griffith’s example with more insight but largely the same message. As the Depression took hold, features like Wild Boys of the Road, Heroes for Sale (both 1933) and Little Man, What Now? (1934) portrayed the country’s economic downturn as the result of mysterious, even unknowable forces.

Comedians actually did a better job depicting economic conditions than did more serious directors, perhaps because many screen clowns positioned themselves as outsiders. In shorts like Easy Street and The Immigrant, Charlie Chaplin took poverty as a given, and immersed viewers into the lives of the poor. The jokes in his feature Modern Times had serious things to say about the impact of assembly lines and surveillance monitors on workers. It also aligned Chaplin’s “Little Tramp” screen persona firmly with the left when he picks up a red construction flag and inadvertently finds himself leading a Communist march.

Buster Keaton made an even more daring connection in his short Cops, filmed not that long after anarchists exploded a bomb on Wall Street. Riding a horse-drawn wagon through a parade of policemen, Keaton’s character uses a terrorist’s bomb to light a cigarette. It’s a stark, blackly humorous moment that must have rattled viewers at the time.

Today’s Occupy Wall Street protests are reminiscent of the tent cities and shanty towns that sprung up across the United States during the Depression. Sometimes called “Hoovervilles,” they were the focal points of often violent clashes between the homeless and authorities. My Man Godfrey (1936) opens in a shanty town and landfill on Manhattan’s East Side, and details with cool, precise humor the gulf between the rich and the poor. Unusually for the time, director Gregory La Cava offered a cure of sorts to unemployment by getting the rich to build a night club where the shanty town stood. In It’s a Gift, one of the best comedies of the decade, W.C. Fields treats a migrant camp as a simple adjunct to his story, an exotic backdrop where he spends a night during his trip to California. It’s a brave gesture for a character who could have been swamped in despair.

Fields’ journey to a West Coast promised land evokes the Dust Bowl migration documented by John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath. When adapting the film version, director John Ford sent camera crews into actual labor camps to document conditions accurately. With its uncompromising screenplay and superb acting, The Grapes of Wrath (1940) stands as one of the finest films to address economic inequality.

Released the following year, Sullivan’s Travels, a comedy written and directed by Preston Sturges, included a sobering, seven-minute montage of soup kitchens, breadlines, flop houses, and missions. The film’s main character, a pampered director of lamebrained comedies like Hay Hay in the Hayloft, sets out to find the “real” America by disguising himself as a hobo. The lessons he learns are as provocative today as when the film was originally released.

World War II changed the focus of Hollywood features. Training barracks and battlefields replaced slums and tent cities as the film industry embraced the war effort. Social problems still existed after the war, of course, but in message dramas like The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), filmmakers tried to offer solutions—to unemployment among veterans, for example. In the 1950s, movies zeroed in on individuals and their neuroses rather than on a collective society. A Place in the Sun (1951) stripped away most of the social commentary from the original Theodore Dreiser novel An American Tragedy to concentrate on the dreamy romance between stars Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor. Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954) was more about a former boxer’s crisis of conscience than it was about a system than exploited dockworkers. Rebel Without a Cause (1955) reduced juvenile delinquency to a teen’s romantic and familial problems.

In the 1960s, Hollywood began to lose its taste for social dramas, preferring to target films to a younger audience. Message films are still released, of course: Norma Rae, Silkwood, The Blind Side, Courageous. But more often than not the message in today’s films is hidden in the nooks and crannies of plots. Is Battle: Los Angeles about our military preparedness? What does Cars 2 say about our dependence on foreign oil? Filmmakers seem to have taken to heart the old line attributed to Samuel Goldwyn. “If you want to send a message,” the producer said, “call Western Union.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)