From Sticks and Stones, Two Artists Make Pinhole Cameras

David Janesko and Adam Donnelly are using materials found in nature to photograph nature

The first camera that David Janesko and Adam Donnelly built washed out to sea with the tide before they could take a single picture. A camera they constructed in the desert of Coachella Valley, California, dried so quickly that it cracked, crumbled and required hasty repairs. This is what happens when you forgo the marvels of modern manufacturing and decide to build your own cameras of materials found in nature: earth, stones, leaves, sticks, mud and sand.

They are photographing landscapes by using the landscape itself.

"In the beginning, we just dug a hole in the ground and tried to make a chamber for a camera," Donnelly says. "It didn't work at first, but we kept going back and the results were just better and better."

Janesko and Donnelly make pinhole cameras, an ancient and simple technology that captures and projects an image without the use of a lens. Instead the light flows into the camera through an aperture—perhaps a fissure in a rock, a crack in a piece of bark or a hole in a shell.

The two artists, who have earned Masters degrees at the San Francisco Art Institute, have constructed about 30 so-called "Site Specific Cameras" in various locations around California. Now, with more than $6,000 raised on Indiegogo, they are on a two-week trip along the Rio Grande, traveling from Texas through New Mexico and into Colorado and building cameras along the way.

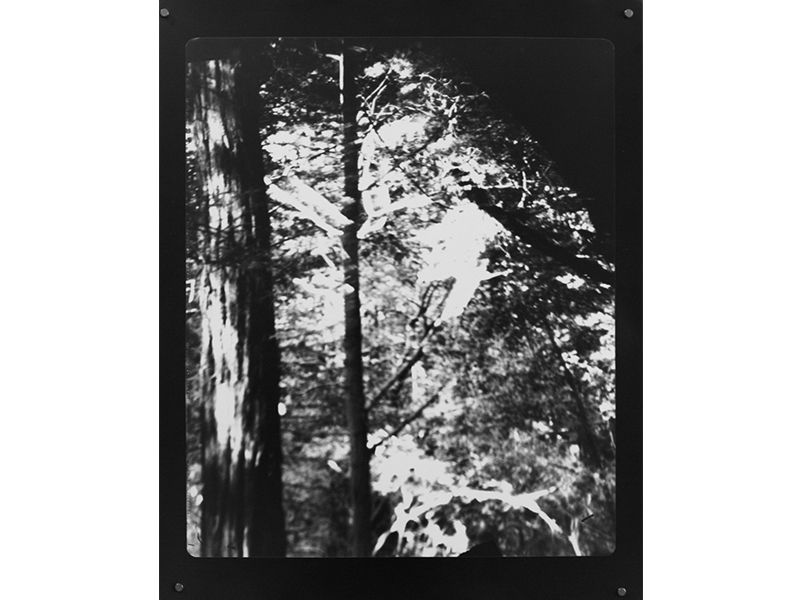

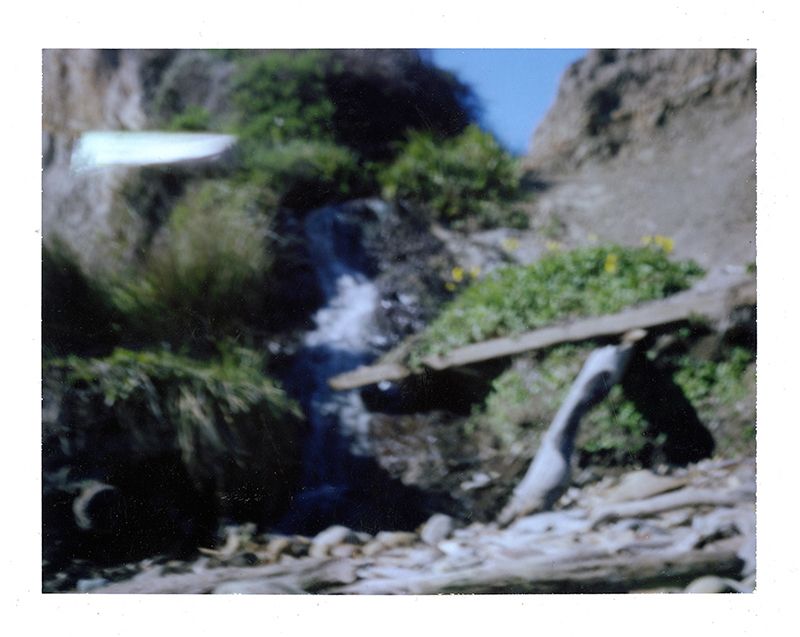

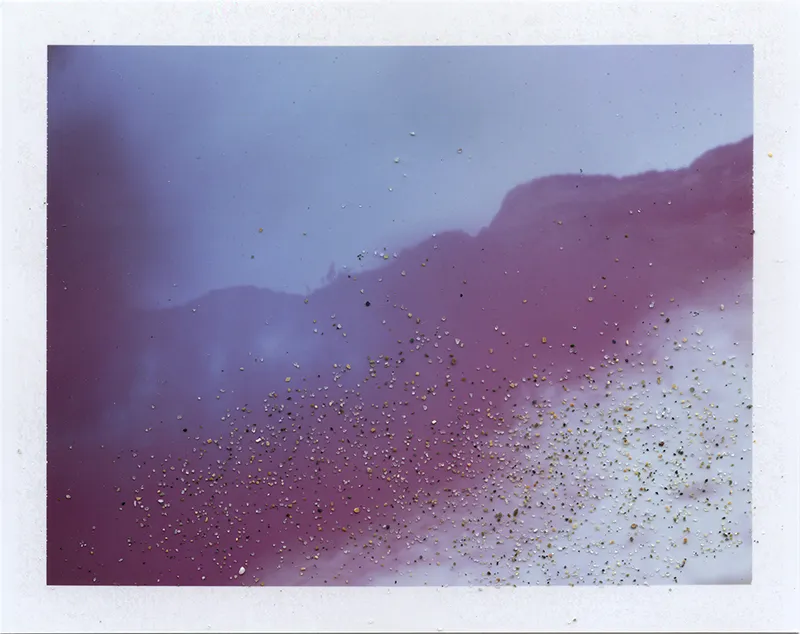

Assembling a camera can take them all day, and the images they create are far from the crisp, high-definition, color-saturated ones that abound in nature photography. Sand sticks to their film and leaves black speckles scattered across the prints. The crumbling Coachella camera let in light leaks that showed up as ghostly flares of white in the final image. Creating sharply focused images is close to impossible with apertures that are never perfectly round.

"I've had people ask: 'Why would you want to go through all this trouble to make this out-of-focus image?'" Donnelly says. But questioning what makes a good photograph is part of the point of the project.

The photographs have a dreamy, misty quality to them. Silhouettes of leaves, sticks and grass that partly obscured the pinhole poke in to the edges of the captured landscape. In some, the pinhole's image is not large enough to cover the entire surface of the photo and the lit scene fades at the edges into darkness. This makes it feel like the viewer is crouched in some small, secret space, observing the environment but also part of it.

"For me," Janesko says, "it is always this magical kind of thing happening. We go in with nothing—maybe a few film holders, nothing else—and we come out with this image of the place where we've been."

The project officially started in 2011, but the seed for it came in 2010 when the two met at the bar across the street from their art school orientation. Donnelly had left the world of professional commercial photography, fed up with producing perfect, sterile photographs and wrangling tons of gear. Janesko was a sculptor with a background in geology and a hankering to experiment with different materials and media. Their conversation over drinks quickly turned to pinhole photography.

People have known the ability of a pinhole to create images in a dark chamber or light-tight box for centuries, writes David Balihar, a photographer based in Prague, the Czech Republic. The Chinese philosopher Mo Ti wrote of images created with a pinhole in the 5th century B.C. About a century later, Aristotle wondered why sunlight passing through the diamond-shaped gaps of wickerwork didn't create diamond-shaped but rather round images. In 1015 A.D., Arabian physicist and mathematician Ibn al-Haytham, called Alhazen, discovered the answer to that question, Balihar adds.

In pinhole images, light from the top of the object in focus—say, a tree—will travel through the pinhole and to the bottom of the projected image. The tree’s leaves seem to brush the bottom of the camera's back wall and the trunk appears to be rooted near the top. Similarly, light from the sides also crisscrosses in the camera body. Alhazen studied these projected upside-down and inverse images and inferred that light must travel in a straight line.

Later, artists used the technology, calling them camera obscuras and sometimes adding mirrors to correct the image's orientation. Leonardo da Vinci was one of the first to describe how to make them in his writings. He used a camera obscura because it flattens a three-dimensional scene while preserving perspective.

Usually, Janesko and Donnelly's cameras are big enough that one photographer or the other can fit inside, though the space may be cramped and uncomfortable. "We usually have to lay down," Donnelly explains. Putting someone inside the body of the camera is necessary, because the enclosed photographer holds unexposed film or photo-sensitive paper up to the projected image created by the pinhole. They've used several types of large-format film and direct positive paper to capture their photographs, though they are now leaning toward processes that only produce a single print.

If multiple prints cannot be made, the single photograph becomes the sole distillation of the time, place, conditions and materials of the place where it was born.

The project’s next site, the Rio Grande, runs through a rift valley, a break in the skin of the Earth's surface where the crust pulled apart and cracked on a massive scale between 35 and 29 million years ago. "The idea of this landscape being shaped by this one event is really interesting to me," Janesko, the former geologist, explains.

The rift and the river that runs through it allowed people to move into the area. "Without that geological event, it wouldn't be a populated area," says Donnelly. "And we wouldn't be able to go there and make cameras if it wasn't for the rift."

They will make nine cameras in the two weeks they are there, documenting the shape of the land with the materials it provides. Traveling with them are filmmakers Matthew Brown and Mario Casillas, who are making a documentary about the "Site Specific Cameras" project. This winter, the photographers also hope to create a book of the images they gather.

Janesko and Donnelly always leave the camera where they construct it. After they've left, the weather and passing creatures (sometimes humans) help it succumb, quickly or slowly but always inevitably, to nature's whims.