Frost Bite

A recently discovered poem by Robert Frost has brought fame—and controversy—to an English student

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/frost-stilling2.jpg)

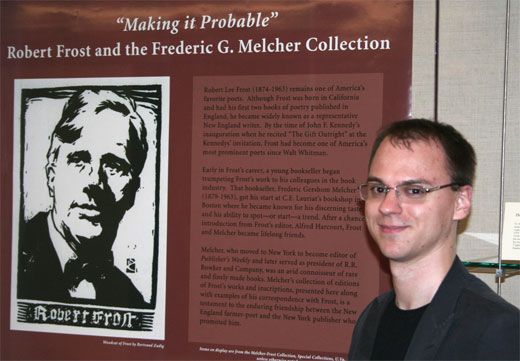

When Robert Stilling, a doctoral candidate in English at the University of Virginia, began a research project last summer on poet Robert Frost, he expected, perhaps, to squeeze out a term paper or two from his research—not to be tossed under a media spotlight brighter than most scholars see in a lifetime.

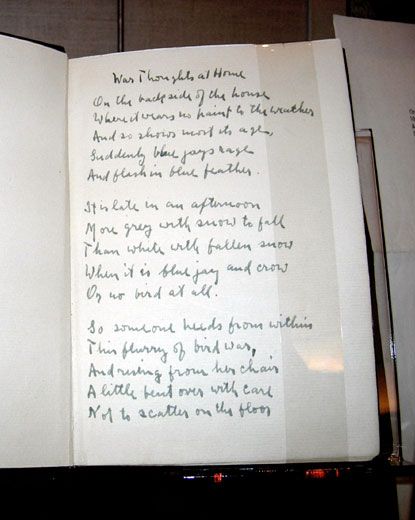

While poring over the University of Virginia's recently acquired Robert Frost collection—a collection so new that most of it had not yet been catalogued—Stilling noticed an inscription in the front of a copy of North of Boston that Frost had sent to his friend, the publisher Frederic Melcher, in 1918. Stilling determined that the inscribed poem, "War Thoughts at Home," had never been published.

After some consideration, Stilling decided to publish the poem, along with a short essay, in the Virginia Quarterly Review. VQR is available at most national bookstores chains, and Stilling felt it would gain more attention there than in a more narrowly focused academic journal.

He was right, it turns out. Too right. Frost's celebrity, combined with the political timeliness of the unearthed war poem and Stilling's role as a grad student sleuth, created the makings of "a good story," says Stilling. "It was sort of a perfect storm."

Instead of focusing on the poem, the media turned its attention on Stilling. Within weeks after the university announced the discovery in September, Stilling was fielding phone calls and interview requests from the New York Times, the Washington Post, CNN, NPR and countless other news organizations—an unexpected burden that he believes would not have been the case had he come across, say, a Wallace Stevens poem, or even a Frost poem on a subject less resonant with America's current political situation.

With the hoopla came criticism. The Chronicle of Higher Education ran a story suggesting that the discovery was not worth all the commotion. After all, VQR editor Ted Genoways had discovered an incomplete draft of Frost verse just seven years earlier. Robert Faggen, a world-renowned Frost scholar who recently compiled an 800-page volume entitled The Notebooks of Robert Frost, also took issue with Stilling's discovery—particularly with his method of presentation. Although the poem was published courtesy of the Frost estate with the intention of making it public, Stilling suspects that Faggen would have preferred to see "War Thoughts" presented more squarely within "the scholarly apparatus," and not, as it became, for a general audience.

The poem's subject also played a role in the excitement, says Genoways. "It's not to be underestimated that the war theme is part of the interest," he wrote in the Fall 2006 VQR, the same issue in which the poem appeared. A work on a less relevant topic might not have generated the same buzz.

A point overlooked by the media is that "War Thoughts at Home" is only one small part of a much larger research project, says Stilling. The poem represents only a portion of the Frost exhibit he curated at University of Virginia's Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, and perhaps an even smaller portion of his research in the future.

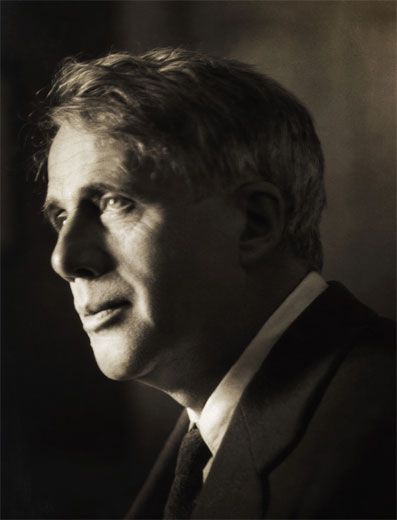

The exhibit, "Making it Probable: The Robert Frost and Frederic G. Melcher Collection," explores the relationship between those two close friends, focusing on how Melcher, acting as a one-man public relations department, catapulted Frost from successful poet to national treasure. The discovery of "War Thoughts at Home" is significant because it exposes a political side of Frost not often seen in his ostensibly local—that is, New England-centric—poetry, but Stilling would like just as much to demonstrate how the celebrity of America's best-loved poet was no accident—that, in fact, it was carefully crafted from start to finish.

The same cannot be said of Stilling's stint in the spotlight. The young scholar calls his recent fame unintentional and a bit unnerving. In his estimation, the value of the discovery and his role in it have yet to be determined and will depend greatly on what he continues to do with his research. Simply put, his career is just beginning, and he is not ready to be categorized strictly as a "Frost scholar."

"A 'Frost scholar' is a rather nice thing to be," says Stilling. "I just happen to have a number of other interests, as most 'Frost scholars' surely do, and it's way too soon to know whom or what I'll be spending my time working on in the next few years."

To the question, "Are there significant disadvantages to your present fame?" Vladimir Nabokov once said, "Lolita is famous, not I." For Stilling, the only foreseeable disadvantage to his present fame is that he might be pigeon-holed as a single-author scholar, but Stilling maintains humbly that it is indeed Frost who is and will always be famous, not he.