Futureproofing California Farmland

Design teams propose new models for farming and suburban development in California’s water-scarce Central Valley

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120514123008farm_470.jpg)

Water scarcity in the U.S. west may seem like a problem that affects western residents alone, but where the national food supply is concerned, the consequences of a water crisis spread quickly in all directions. The San Joaquin Valley is the most productive agricultural region in the world, according to a Reuters data report on California agriculture and water supply. The state produces “over half of U.S. fruits, nuts and vegetables and over 90 percent of U.S. almonds, artichokes, avocados, broccoli and processing tomatoes,” and is the nation’s largest dairy supplier. If this food production powerhouse falters due to drought, failed hydraulic infrastructure, or insufficient economic resources to support existing systems, the grocery store landscape and the contents of refrigerators everywhere change.

Some people consider threats to the food system to be a national security problem. In his 2008 open letter to the President-Elect (one month before Obama’s win), Michael Pollan cited the resource-intensive “vegetable-industrial complex” as the critical issue for the next commander-in-chief, given its starring role in other crises like energy dependence, healthcare and climate change. In his proposed list of solutions, Pollan called for “reregionalizing the food system”—and here the door swings open to invite designers, architects, engineers, and land use planners into the conversation. “The best way to protect our food system against such threats is obvious: decentralize it,” Pollan declared. This “means building the infrastructure for a regional food economy — one that can support diversified farming and, by shortening the food chain, reduce the amount of fossil fuel in the American diet.”

Pollan didn’t talk a tremendous amount about water in his manifesto—fossil fuels were such a central aspect of the last campaign cycle. But in the years since, it’s been said innumerable times that “peak water” may follow on the heels of peak oil (though the economic and legal nuances of such a comparison have been called to account a few times). In California, the vast majority of the state’s water budget goes to agriculture (up to 85 percent, depending on whom you ask), and groundwater reserves—the primary source of irrigation water—are steadily declining (more on that in another post).

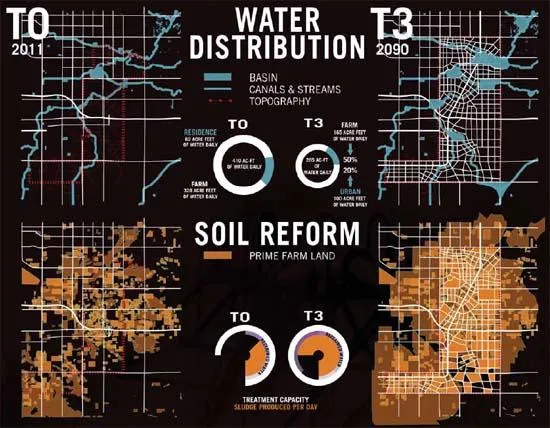

While experts investigate the science of the crisis, organizations like the Arid Lands Institute ask design practitioners to propose applied strategies for reformatting farmland. Their recent competition and current exhibition showcase several proposals that respond to the notion of “reregionalizing.” Two focus on Fresno, California—the metropolitan hub of the farm-dense Central Valley.

A team of design students from the California College of the Arts submitted FresNOW!, a concept that considers the cultivation and harvest not only of food, but also of local water, energy and fertilizer. The four-part scheme would guide the region toward more sustainable development overall, producing power through wind, sun and anaerobic digestion; creating soil with worms, fish and compost; and planting a more diverse and climate-appropriate crop range that can be rotated regularly. In this scenario, the job description of a “farmer” broadens to include the harvesting of solar energy, for example, meaning the area’s employment picture becomes more inclusive, and the economic base more diverse.

The proposal calls for specific policy changes by 2050, such as mandatory metering of the agricultural water supply; prohibiting the use of drinking water for crop irrigation (instead recycled waste water and grey water would be used); eliminating government subsidies on water for industrial scale farms; and requiring farms to meet a percentage of their own energy needs by growing biofuel crops. The presentation of FresNOW!—its “brand identity,” if you will—has a revolutionary tenor, even invoking socialism as a model for the future farm labor force. But the practicalities are well within today’s familiar framework for sustainable design—renewable energy, localized economies, byproduct recycling. When knit together, the strategies paint a picture of a near future in which our most productive agricultural region is also our most resilient.

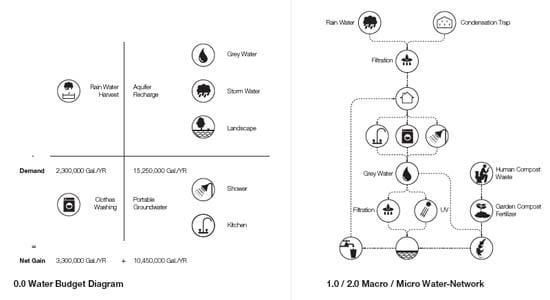

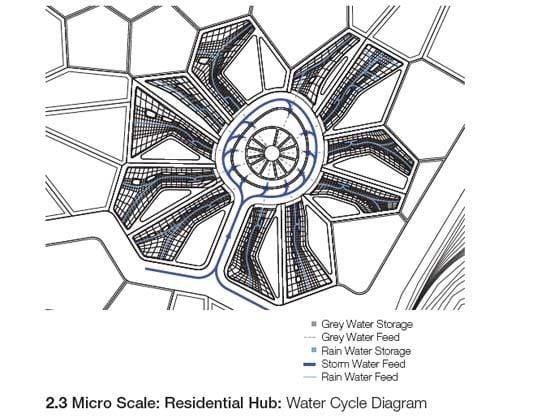

While FresNOW! looks mostly at the Central Valley’s non-residential systems, another Drylands Design Competition proposal uses suburban housing developments as its leverage point. Net Gain: Constructing New Growth Ecologies for the American West was conceived by an architect and an environmental consultant collaborating around the idea that sustainable design should not just achieve “net zero” resource consumption—it should be able to promote growth according to a paradigm that decouples growth from environmental degradation. In their vision of a future suburb, “residential development contains the same housing density as the average development in the area. The difference is the area typically devoted to front lawns is given over to indigenous green-ways, hedgerow habitats for indigenous pollinators, high value organic row agriculture, community gardens, energy production hubs and single family residences off the grid.”

The suburban development comes to look like a hub-and-spoke network in which rain water capture, solar energy collection, food production, and other functions geared toward self-sufficiency are integrated into the blueprint of the place. As a retrofit, such a complete integrated systems approach might be difficult to implement, but for future new developments—of which there are always more in the sprawling territory of central California—this could be a model for residential growth that feeds, rather than starves, the surrounding agricultural web.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)