Gauguin’s Bid for Glory

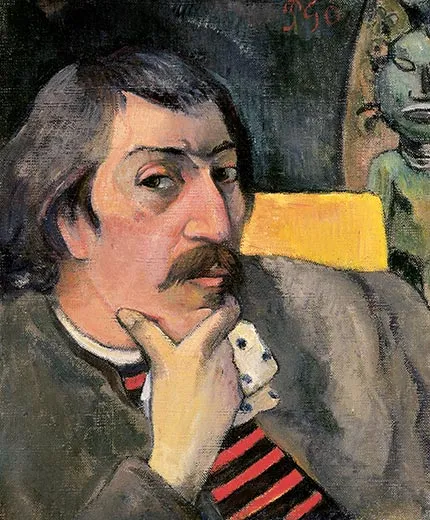

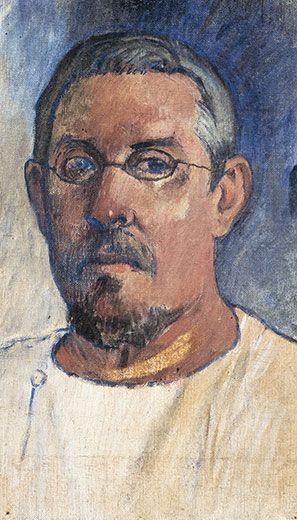

Of all the images created by the artist Paul Gauguin, none was more striking than the one he crafted for himself

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Gauguin-Te_Nave_Nave_Fenua-1892-631.jpg)

Paul Gauguin did not lack for confidence. “I am a great artist, and I know it,” he boasted in a letter in 1892 to his wife. He said much the same thing to friends, his dealers and the public, often describing his work as even better than what had come before. In light of the history of modern art, his confidence was justified.

A painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramist and writer, Gauguin stands today as one of the giants of Post-Impressionism and a pioneer of Modernism. He was also a great storyteller, creating narratives in every medium he touched. Some of his tales were true, others near-fabrications. Even the lush Tahitian masterpieces for which he is best known reflect an exotic paradise more imaginary than real. The fables Gauguin spun were meant to promote himself and his art, an intention that was more successful with the man than his work; he was well known during his lifetime, but his paintings sold poorly.

“Gauguin created his own persona and established his own myth as to what kind of a man he was,” says Nicholas Serota, the director of London’s Tate, whose exhibition, “Gauguin: Maker of Myth,” traveled last month to Washington’s National Gallery of Art (until June 5). “Gauguin had the genuine sense that he had artistic greatness,” says Belinda Thomson, curator of the Tate Modern’s exhibition. “But he also plays games, so you are not sure whether you can take him literally.”

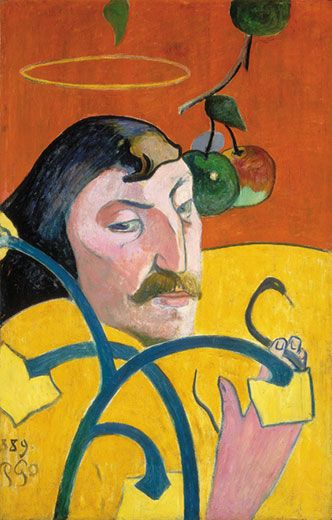

Of the nearly 120 works on display in Washington, several tantalizing self-portraits depict Gauguin in various guises: struggling painter in a garret studio; persecuted victim; even as Christ in the Garden of Olives. An 1889 self-portrait shows him with a saintly halo and a devilish snake (with Garden of Eden apples for good measure), suggesting just how contradictory he could be.

Certainly the artist would have been pleased by the renewed attention; his goal, after all, was to be famous. He dressed bizarrely, wrote self-serving critiques of his work, courted the press and even handed out photographs of himself to his fans. He was often drunk, belligerent and promiscuous—and possibly suicidal. He removed himself from Paris society to increasingly exotic places—Brittany, Martinique, Tahiti and finally to the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia—to escape a world he felt was modernizing too quickly.

His vivid colors, flattening of perspective, simplified forms and discovery of so-called primitive art led scholars to credit him with influencing Fauvism, Cubism and Surrealism. His powerful personality also helped establish the convention of artist as iconoclast (think Andy Warhol or Julian Schnabel). “He drew from French symbolism and poetry, from English philosophy, the Bible and the South Seas legends,” says Mary G. Morton, the curator of French paintings at the National Gallery. “He took a multicultural approach to his work.”

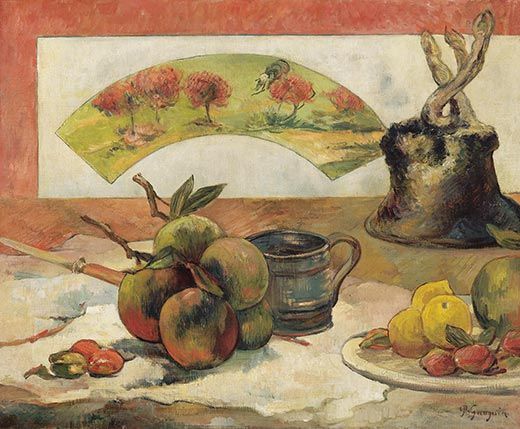

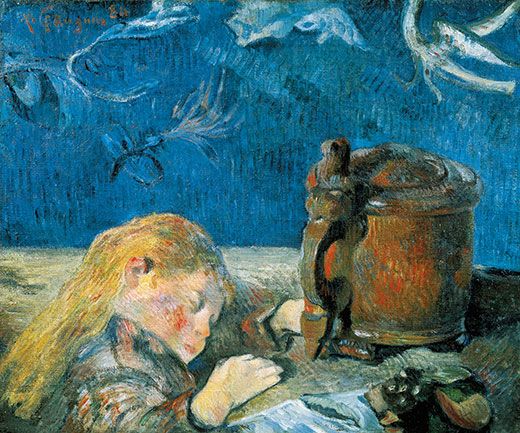

Soyez mystérieuses (Be mysterious) is the title Gauguin gave to a wood bas-relief carving of a female bather. It was a precept by which he lived. As if his paintings were not sufficiently full of ambiguity, he gave them deliberately confusing titles. Some were in the form of questions, such as Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, a tropical scene as puzzling as its title. Others were written in Tahitian, a language some potential buyers found off-putting. Even in his earliest pictures Gauguin would insert some odd object: an outsize tankard, for example, in the otherwise charming portrait of his sleeping young son, Clovis. In The Loss of Virginity, the strange element is a fox, whose paw casually rests on the breast of a naked woman lying in a Brittany landscape. (The model, a Paris seamstress, would soon bear Gauguin’s child, a daughter named Germaine.)

The artist himself was likely the fox in the picture, an animal he claimed was the “Indian Symbol of perversity.” One-eighth Peruvian, this son of bourgeois Parisians often referred to himself as part savage. His first dealer, Theo van Gogh (brother of Vincent), suggested that Gauguin’s work was hard to sell because he was “half Inca, half European, superstitious like the former and advanced in ideas like certain of the latter.”

The South Seas provided Gauguin some of his best legend-making opportunities. Disappointed that many traditional rituals and gods had already disappeared from Tahitian culture, he simply reconstructed his own. Back in Paris, he created one of his most enigmatic sculptures: a grotesque female nude with bulging eyes, trampling a bloody wolf at her feet while grasping a smaller creature with her hands. Gauguin considered it his ceramic masterpiece, and wanted it placed on his tomb. Its title: Oviri, Tahitian for “savage.”

Gauguin’s life was interesting enough without all the mythologizing. He was born Eugene Henri Paul Gauguin on June 7, 1848, in Paris to a political journalist, Clovis Gauguin, and his wife, Aline Marie Chazal, the daughter of a prominent feminist. With revolutions sweeping Europe when Paul was barely a year old, the family sought the relative safety of Peru, where Clovis intended to start a newspaper. But he died en route, leaving Aline, Paul and Paul’s sister, Marie, to continue on to Lima, where they stayed with Aline’s uncle.

Five years later they returned to France; Gauguin was back on the high seas by the time he was 17, first in the merchant marine, then in the French Navy. “As you can see, my life has always been very restless and uneven,” he wrote in Avant et Après (Before and After), autobiographical musings that were published after his death. “In me, a great many mixtures.”

When Gauguin’s mother died, in 1867, her close friend Gustave Arosa, a financier and art collector, became his guardian. Arosa introduced his ward to Paris painters, helped him get a job as a stockbroker and arranged for him to meet Mette Gad, the Danish woman he would marry in 1873.

At the time, Gauguin was surrounded by people who wanted to be artists, including fellow stockbroker Émile Schuffenecker, who would remain a friend even after others tired of Gauguin’s antics. They attended art shows, bought French pictures and Japanese prints, and dabbled in oils. Though he was just a Sunday painter, Gauguin had a landscape accepted at the important Paris Salon of 1876. And six years later, when he lost his job in the stock market crash of 1882, Gauguin took up painting full time, even though he had a wife and four children to support. “No one gave him the idea to paint,” Mette told one of her husband’s biographers much later. “He painted because he could not do otherwise.”

To save money, the family, which would ultimately include five children, moved to Mette’s family home in Copenhagen. Gauguin described himself as “more than ever tormented by his art,” and he lasted only half a year with his in-laws, returning with son Clovis to Paris in June 1885. Clovis was put in Marie’s care; Gauguin never lived with his family again.

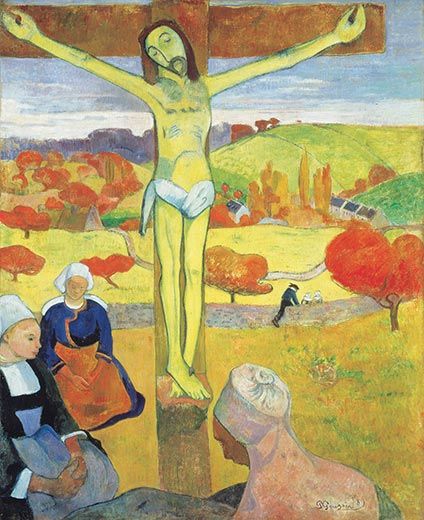

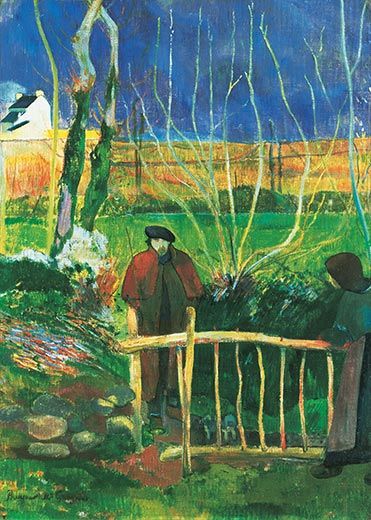

A quest for ever-cheaper lodgings led him to Brittany in 1886, where the artist soon wrote to his wife with characteristic bravado that he was “respected as the best painter” in Pont-Aven, “although that doesn’t put any more money in my pocket.” Artists were drawn to the village on France’s western tip for the ruggedness of its landscape, the costumed inhabitants who were willing to pose and the Celtic superstitions overlaid with Catholic rituals that pervaded daily life. “I love Brittany,” Gauguin wrote. “I find the wild and the primitive here. When my clogs resonate on this granite ground, I hear the muffled, powerful thud that I’m looking for in painting.”

Though an admirer of Claude Monet, a collector of Paul Cézanne, a student of Camille Pissarro and a friend of Edgar Degas, Gauguin had long sought to go beyond Impressionism. He wanted his art to be more intellectual, more spiritual and less reliant on quick impressions of the physical world.

In Pont-Aven, his work took a radically new direction. His Vision of the Sermon was the first painting in which he used vibrant colors and simple forms within bold, black outlines, in a style called Cloisonnism reminiscent of stained glass. The effect moved the painting away from natural reality toward a more otherworldly space. In Sermon, a tree limb on a field of vermilion divides the picture diagonally, Japanese style. In the foreground a group of Breton women, their traditional bonnets looking like “monstrous helmets” (as Gauguin wrote to Vincent van Gogh), have closed their eyes in reverie. On the top right is their collective religious experience: the biblical scene of Jacob wrestling with a gold-winged angel. One critic’s response to the evocative, hallucinatory picture was to anoint Gauguin the master of Symbolism.

Pleased with the large canvas, Gauguin enlisted artist friends to carry it for presentation to a stone church nearby. But the local priest refused the donation as “nonreligious and uninteresting.” Gauguin seized on this affront as a public relations opportunity, writing outraged letters and encouraging his collaborators to spread the word back in Paris. As art historian Nancy Mowll Mathews has noted, “Gauguin’s Vision of the Sermon gained more notoriety by being rejected than it ever would have from being politely accepted by the priest and just as politely put into a closet.”

In 1888, as is now legendary, Vincent van Gogh invited Gauguin, whom he had met in Paris, to join him in Arles to create an artists’ “Studio of the South.” At first Gauguin demurred, arguing that he was ill, debt-ridden or too involved in a prospective business venture. But Theo van Gogh offered the perpetually poor Gauguin a reason to accept his brother’s invitation—a stipend in exchange for a painting a month. Gauguin’s two-month stay in Arles’ Yellow House proved productive—and fraught. “Vincent and I do not agree on much, and especially not on painting,” Gauguin wrote in early December. In a drunken argument soon after, van Gogh approached Gauguin with a razor. Gauguin fled, and van Gogh turned the razor on himself, cutting off part of his ear. Even so, the two corresponded until van Gogh killed himself 18 months later.

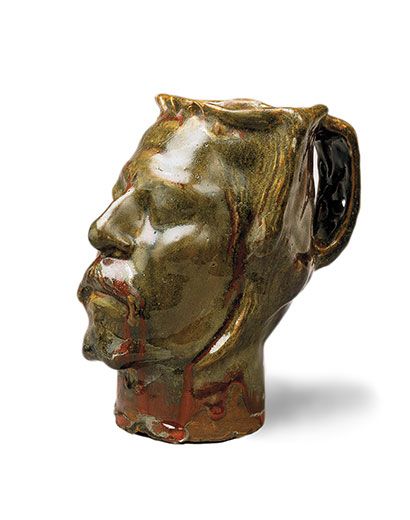

After Gauguin returned to Paris from Arles, he created one of his most bizarre carvings, Self-Portrait Vase in the Form of a Severed Head. Perhaps an allusion to John the Baptist, this stoneware head drips with macabre red glaze. Did the gruesome image come from the bloody experience with van Gogh? The guillotining of a convicted murderer Gauguin had recently witnessed? Or was it simply a nod to the then current fascination with the macabre?

The Universal Exposition of 1889, for which the Eiffel Tower was built, marked a defining moment for Gauguin. He enthusiastically attended Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, admired the plaster casts of the Buddhist Temple of Borobudur and viewed the paintings on display. Artists who weren’t included in these state-sponsored exhibits tried to capitalize on the fair’s popularity (28 million people turned out) by organizing their own shows outside the perimeter. But the uninvited Gauguin, supported largely by the devoted Schuffenecker, audaciously mounted a group show at Volpini’s Café on the fairgrounds.

Gauguin was particularly taken with the Exposition’s ethnographic displays, featuring natives from France’s colonies in Africa and the South Pacific. He painted Javanese dancers, collected photographs of Cambodia and otherwise whetted his desire for a tropical Elysium. He wanted, he wrote, to “be rid of the influence of civilization ...to immerse myself in virgin nature, see no one but savages, to live their life.” He was also aware that “novelty is essential to stimulate the stupid buying public.”

It was likely the Exposition that pointed him to Tahiti. As he prepared for his trip the following year, he wrote to a friend that “under a winterless sky, on marvelously fertile soil, the Tahitian has only to reach up his arms to gather his food.” The description comes almost word for word from the Exposition’s official handbook.

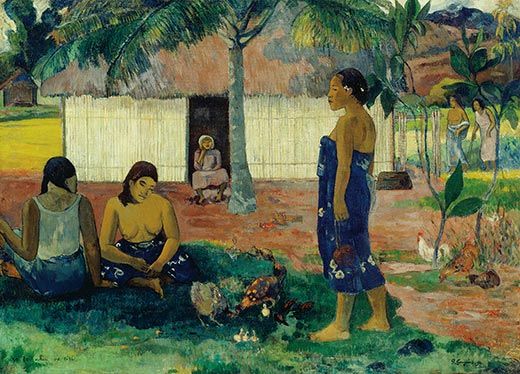

Arriving in French Polynesia’s capital, Papeete, in June 1891, Gauguin found it much less exotic than he had imagined—or hoped. “The Tahitian soil is becoming completely French,” he wrote to Mette. “Our missionaries had already introduced a good deal of protestant hypocrisy and wiped out some of the poetry” of the island. The missionaries had also transformed women’s fashion, doubtless to Gauguin’s dismay, from the traditional sarong and pareu to cotton dresses with high collars and long sleeves. He soon moved to the village of Mataiea, where the locals, as well as the tropical landscape, were more to his liking because they were less Westernized.

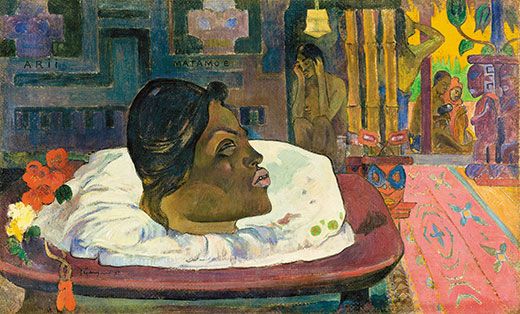

Gauguin acknowledged the demise of the old Tahitian order in his disquieting painting Arii Matamoe (The Royal End). The centerpiece is a severed head, which Gauguin coolly described as “nicely arranged on a white cushion in a palace of my invention and guarded by women also of my invention.” The inspiration for the painting, if not the decapitation, may have been the funeral of King Pomare V, which Gauguin witnessed soon after arriving on the island; Pomare was not beheaded.

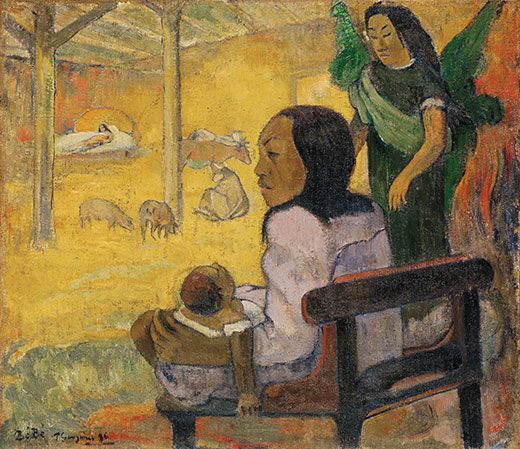

Though a vehement anticleric, the artist couldn’t completely shake his Catholic heritage. His respectful The Last Supper contrasts the brilliance of Christ’s chrome-yellow halo with sober tribal carvings. In Nativity, a Tahitian nurse holds the baby Jesus, while a green-winged angel stands guard and an exhausted Mary rests.

In his notebooks as well as his imagination Gauguin carried the works that meant the most to him. Among them: photographs of Egyptian tomb paintings, Renaissance masterpieces and a 1878 auction catalog of his guardian Arosa’s collection, with works by Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet and Eugene Delacroix. Like many artists today—Jeff Koons, Richard Price and Cindy Sherman, among them—Gauguin expropriated freely from them all. “He didn’t disguise his borrowings, which were wide-ranging,” says curator Thomson. “That’s another way in which he is so modern.”

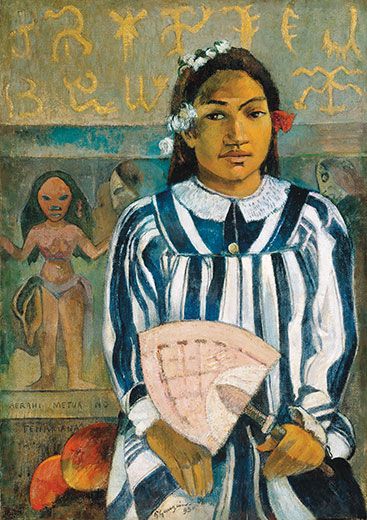

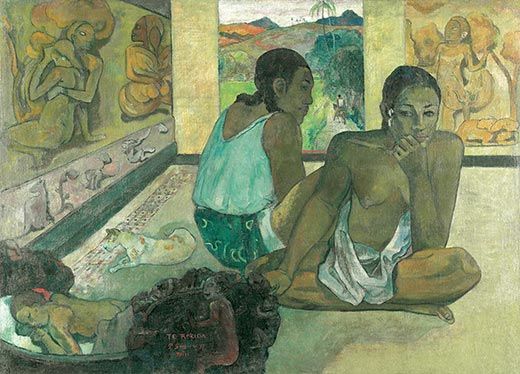

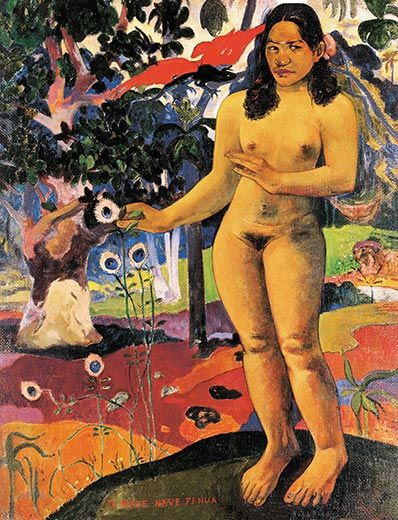

On the wall of his bamboo hut in Mataeia, Gauguin hung a copy of Olympia, Édouard Manet’s revolutionary painting of a shamelessly nude prostitute with a flower in her hair. Ever the mischief-maker, Gauguin led his young mistress Tehamana to believe it was a portrait of his wife. Tehamana was the model for several works in the exhibition, including Merahi Metua no Tehamana (The Ancestors of Tehamana), Te Nave Nave Fenua (The Delightful Land) and Manao tupapau (The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch).

Though Manet’s masterpiece, which Gauguin had once copied, doubtless inspired Manao tupapau, Gauguin’s lover lies not on her back like Olympia but on her stomach, her eyes looking over her shoulder in terror at the tupapau, a black-hooded spirit, near the foot of the bed.

“As it stands, the study is a little indecent,” Gauguin acknowledged in Noa Noa, an account of his Tahitian travels he wrote after returning to Paris. “And yet, I want to do a chaste picture, one that conveys the native mentality, its character, its tradition.” So Gauguin created a back story for the painting, one that may or may not be true. He claimed that when he returned to the hut late one night, the lamps had gone out. Lighting a match, he so frightened Tehamana from her sleep that she stared at him as though he were a stranger. Gauguin supplied a reasonable cause for her fear—“the natives live in constant fear of [the tupapau].” Despite his efforts to control and moderate the narrative, the Swedish Academy of Fine Arts found Manao tupapau unseemly and removed it from a Gauguin exhibition in 1898.

Though Gauguin’s two years in Tahiti were productive—he painted some 80 canvases and produced numerous drawings and wood sculptures—they brought in little money. Discouraged, he decided to return to France, landing in Marseilles in August 1893 with just four francs to his name. But with help from friends and a small inheritance, he was soon able to mount a one-man show of his Tahitian work. Critical reception was mixed, but critic Octave Mirbeau marveled at Gauguin’s unique ability to capture “the soul of this curious race, its mysterious and terrible past, and the strange voluptuousness of its sun.” And Degas, then at the height of his success and influence, bought several paintings.

He turned his Montparnasse studio into an eclectic salon for poets and artists. Playing for recognition, he dressed in a blue greatcoat with an astrakhan fez, carried a hand-carved cane and enhanced his striking image with yet another young mistress, the teenage Anna the Javanese, and her pet monkey. She accompanied Gauguin to Pont-Aven, where Gauguin planned to spend the summer of 1894. But instead of enjoying the artistic stimulus of Brittany, Gauguin soon found himself in a brawl with Breton sailors, who were picking on Anna and her monkey, that left him with a broken leg. While he was recovering, Anna returned to Paris and looted his apartment, putting an emphatic end to their months-long relationship.

Feminists might see Anna’s action as payback for Gauguin’s long abuse of women. After all, he abandoned his wife and children, sought out underage lovers and lived a life of hedonism that ended in heart failure exacerbated by syphilis. Still, he often expressed sadness over his failed marriage and missed his children in particular. And he created far more female images than males, sharing with his Symbolist contemporaries the idea of the Eternal Feminine, in which women were either seductive femmes fatales or virtuous sources of spiritual energy. His handsome, enigmatic Tahitian women have become icons of modern art.

Then there are the elaborate door carvings that identify Gauguin’s final residence in the remote, French Polynesian Marquesas Islands, some 850 miles northeast of Tahiti. He went there at age 53 in September 1901 to find, he said, “uncivilized surroundings and total solitude” that will “rekindle my imagination and bring my talent to its conclusion.” The door’s sans-serif carved letters spell out Maison du Jouir (House of Pleasure)—effectively, a place of ill-repute. Perhaps to taunt his neighbor, the Catholic bishop, the portal features standing female nudes and the exhortation to “Soyez amoureuses vous serez heureuses”—“Be in love and you will be happy.” Tate curator Christine Riding suggests that the work may not be as anti-feminist as today’s mores might indicate. Gauguin may be offering women a liberating idea: Why shouldn’t they enjoy lovemaking as much as men?

Gauguin spent his last days battling colonial authorities over alleged corruption, as well as what he considered unwarranted regulations of alcohol and child morality. In native dress and bare feet, he also argued—in court—that he should not have to pay taxes. “For me, it is true: I am a savage,” he wrote to Charles Morice, the collaborator on his memoir Noa Noa. “And civilized people suspect this, for in my works there is nothing so surprising and baffling as this ‘savage in spite of myself’ aspect. That is why [my work] is inimitable.”

As his health deteriorated, Gauguin considered returning to Europe. His friend Daniel de Monfreid argued against it, saying the artist was not up to making the trip and that a return to Paris would jeopardize his growing reputation. “You are at the moment that extraordinary, legendary artist who sends from the depths of Oceania his disconcerting, inimitable works, the definitive works of a great man who has disappeared, as it were, off the face of the earth.”

Sick and near-penniless, Gauguin died at age 54 on May 8, 1903, and was buried in the Marquesas. A small retrospective was held in Paris that year. A major exhibition of 227 works followed in 1906, which influenced Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, among others. Gauguin was famous at last.

Ann Morrison is the former editor of Asiaweek and co-editor of Time’s European edition. She now lives in Paris.