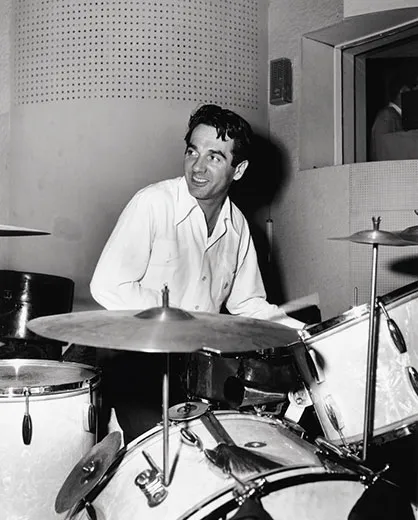

Gene Krupa: a Drummer with Star Power

Rising to fame with the Benny Goodman band, Gene Krupa was the first superstar drummer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/DifferentDrummer-drumset-gene-krupa-benny-goodman-631.jpg)

When I was 7, my parents gave my brother a drum set. My brother was 14, and in my eyes he was a god; the drums he beat unmercifully in our living room added immeasurably to his aura. Made by Slingerland, they had a faux mother-of-pearl finish that caught the light in a way that suggested nothing short of magic.

A big part of this magic was that my brother’s drums—a snare, a big bass, two tom-toms (drums without snares), a high-hat (two cymbals brought together by a foot pedal), and two or three other cymbals—were exactly like those used by the great Gene Krupa. A drummer who had risen to fame with the Benny Goodman band, Krupa was to swing-era percussion what Gary Cooper and Humphrey Bogart were to movies of the day.

“Krupa was the first star drummer, the percussionist who transformed the drums from merely time-keeping to a prominent role as a solo instrument,” says John Edward Hasse, curator of American music at the Smithsonian Institution. Great drummers, including Buddy Rich and Max Roach, would follow his lead, but Krupa was the pioneer who gave percussionists the chance to take center stage. The drum set that inspired my brother now resides in the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

Eugene Bertram Krupa was born in Chicago in 1909 andbegan playing drums professionally in the mid-1920s; he was soon working with such greats as bandleaders Eddie Condon and Glenn Miller, cornetist Bix Beiderbecke and saxophonist Coleman Hawkins. After he joined the Goodman band in 1934, Krupa—with his musicianship and good looks—became a major attraction. He was also a member of the Benny Goodman Quartet, with Teddy Wilson on piano, Lionel Hampton on vibraphone, and Goodman on clarinet. The quartet was one of the first integrated jazz groups, and certainly the most famous.

At a groundbreaking Benny Goodman concert in Carnegie Hall on January 16, 1938, Krupa’s sensational driving beat behind “Sing Sing Sing”—and his reprise of the number in the movie Hollywood Hotel—defined him as the very model of a modern drummer. According to Kennith Kimery, executive producer of the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, Krupa’s fame had an unhappy consequence. “Krupa insisted on having drums in the forefront of the band. Benny Goodman wanted the audience’s focus to be on him,” Kimery says. “With certain numbers, Gene stole Benny’s thunder; in the end that cost him his job.” After leaving Goodman, Krupa formed his own band and became a frequent performer on television. He died in 1973 at age 64.

Around the time he left the Goodman orchestra in 1938, Krupa picked up a new set of Slingerland drums at the Fred Walker Instrument Company in Baltimore, Maryland, leaving his old instruments—emblazoned with his initials as well as those of Benny Goodman—at the company. In 1940, Walker customer Donald Hay, who played drums with a local swing band, bought the set. From 1944 to 1946, Hay served in the Navy, much of that time aboard the destroyer USS Wallace Lind, where he played drums with the ship’s band.

“After he got out of the Navy, he kept the drums in the basement and played along to big-band shows on the radio,” Leslie Schinella, the youngest of Hay’s three children, told me. “He had an Esso station and worked very long hours, so we heard him play mostly on Sundays.”

Hay died in September 2009 at 89. A hospice worker, Jennifer Betts, who had taken care of him, was the daughter of Keter Betts, singer Ella Fitzgerald’s bass player; Jennifer knew someone at the Smithsonian, and Schinella and her siblings agreed to donate their father’s drums to the Institution. “If a dealer had bought [them],” Schinella says, “we’d never have known where they went. But at the Smithsonian, they would be seen by a lot of people.”

When curator Hasse learned of the proposed gift, he and Kimery drove to Catonsville, Maryland, to verify their provenance. “The drums were the right vintage,” Kimery says. “They had calfskin heads, not modern synthetics; the tom-tom was on a tripod stand of the kind that isn’t used anymore. And of course there were the initials.”

At the Smithsonian, the Krupa drums will join a set used by Buddy Rich. Since the two masters were friendly competitors for the unofficial title of Crown Prince of Percussion, it’s a fitting reunion. Drum roll, please...

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)