Gene Tunney’s Gloves Enter the Ring

Fans still argue about who really won the 1927 “long count” fight between Gene Tunney and Jack Dempsey

Most sports controversies live for only a season or two. But some, like the athletes involved, have stronger legs. One of the most enduring of these events occurred on September 22, 1927, in a heavyweight championship bout between the 30-year-old champion, Gene Tunney, and the 32-year-old former champion, Jack Dempsey. Tunney, nicknamed the Fighting Marine, had taken the title from Dempsey a year before. The rematch at Soldier Field in Chicago was of national and international interest, with fans glued to their radios and gate receipts of more than $2.5 million. “My father earned one million for the fight,” says Jay Tunney, one of the fighter’s three sons, noting that the prize money constituted an astronomical payday in the 1920s. “The popularity of the match had a unifying power in the U.S.,” he adds.

Jay and his older brother John V. Tunney, a former U.S. senator from California, recently donated the six-ounce gloves Tunney wore in this epochal match to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History (NMAH). Eric Jentsch, deputy chair of the division of culture and the arts, calls them “an important addition to other [NMAH] historical boxing artifacts, including John L. Sullivan’s championship belt, gloves used by Dempsey and Joe Louis, and the robe Muhammad Ali wore for the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ with George Foreman in Zaire.”

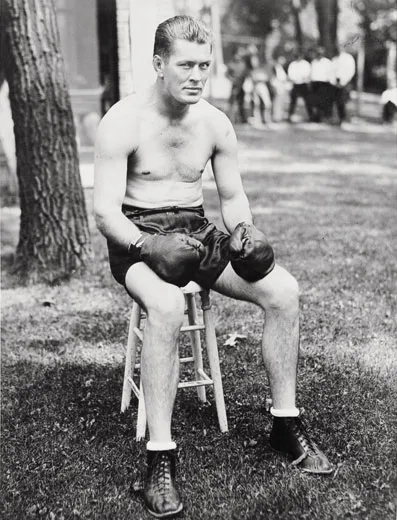

Tunney, an Irish-American who had boxed since his teen years in New York City, was a stylish, intelligent fighter, as well as an avid reader. Dempsey had called him a “big bookworm,” close to slander in the fight game. In the rematch, Tunney was well ahead on the judges’ scorecards when, in the seventh round, Dempsey knocked him to the canvas with a sweeping left hook.

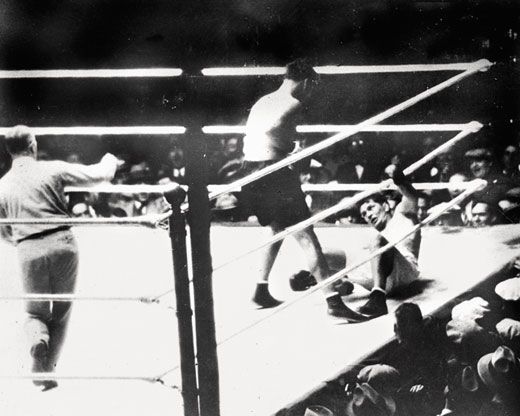

During his storied career, Dempsey—an aggressive hitter nicknamed the Manassa Mauler—typically hovered over a downed opponent and began swinging the instant the man got up. But a new rule in boxing decreed that when a knockdown occurred, the fighter on his feet had to go to the farthest neutral corner before the referee began his count. But Dempsey, perhaps doing what came naturally to him, stayed in his own corner, only a few feet from Tunney. While the champion cleared his head after the first knockdown of his professional career, five seconds elapsed before referee Dave Barry got Dempsey to move away so the count could begin. Tunney, in a sitting position with one arm on the lowest rope, watched the referee intently. Jay Tunney—who tells the story in a new book, The Prizefighter and the Playwright, an account of his father’s unlikely friendship with George Bernard Shaw—writes that one of Tunney’s corner men, someone he’d known since boxing in the Marines, shouted at him to wait until nine to get back up, to take full advantage of the time to recover.

At Barry’s count of “nine,” Tunney was on his feet, moving lightly away from the charging Dempsey. Toward the end of the round, Tunney landed a short, hard right to Dempsey’s body that caused him to grunt audibly and probably ended any hopes the ex-champ might have had about a quick end to the bout. Tunney continued on the offensive, knocking Dempsey down in the next round and taking the remaining rounds on points; he won the fight in a unanimous decision. The outfought Dempsey would not box professionally again. Jay Tunney says that “a third match would probably have brought in even more money for both men. But Dempsey’s eyes had taken a beating, and he may have been worried about losing his sight if he fought again.”

The next day, a New York Times headline said, in part, “Dempsey Insists Foe Was Out in 7th, Will Appeal,” and the “long count” controversy was born. But YouTube allows us to view footage of the round today: it seems clear that Tunney was down but far from out. Jay Tunney recalls his father saying that he could have gotten up at any time, and his sure-footed ability to evade Dempsey underscores that contention. “My dad trained with absolute devotion to becoming the heavyweight champ,” says Jay Tunney, “and he was in the best shape of any fighter of the time. His credo was, ‘Drink two quarts of milk a day and think of nothing but boxing.’”

Tunney retired undefeated after another year and one more fight. Not until 1956 would another heavyweight champion, Rocky Marciano, retire undefeated. Jay Tunney says that his father “loved the sport, but used boxing as a vehicle to get to where he wanted to be—which was to be a cultured man.” In this, as in boxing, Tunney triumphed. He became a successful businessman, and in addition to Shaw, made a number of literary friends, including Ernest Hemingway and Thornton Wilder. Attesting to his sportsmanship, Tunney also maintained a lifelong friendship with his greatest adversary—Jack Dempsey.

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)