George Ault’s World

Structured with simple lines and vivid colors, the paintings of George Aultcaptured the chaotic 1940s in a unique way

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/George-Ault-Daylight-Russells-Corners-631.jpg)

The black barn in George Ault’s painting January Full Moon is a simple structure, bound by simple lines. Yet its angular bones give it a commanding presence. The barn stands at attention, its walls planted in moonlit snow and its peak nosing toward a deep blue sky. It is bold and brawny, and as Yale University art history professor Alexander Nemerov puts it, a barn with a capital “B,” the Barn of all barns.

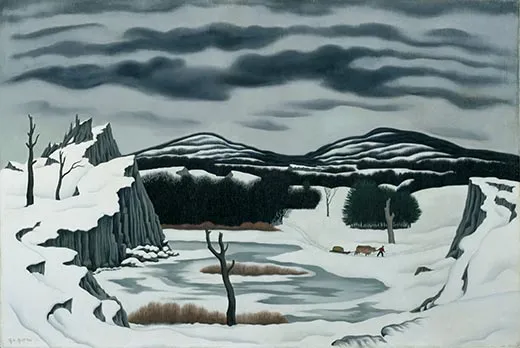

A little-known American artist, George Ault had the ability in his painting to take specific locations in Woodstock, New York, where he lived from 1937 until his death in 1948, and make them seem universal. Nemerov says that places like Rick’s Barn, which Ault passed on walks with his wife, Louise, and Russell’s Corners, a lonely intersection just outside of town, held some “mystical power” to the artist. He fixated on them—painting Russell’s Corners five times in the 1940s, in different seasons and times of day—as if they contained some universal truth that would be revealed if he and the viewers of his paintings meditated on them long enough.

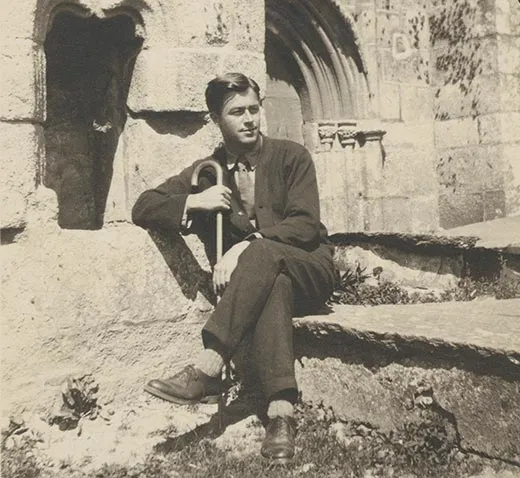

After fastidiously studying his scenes, Ault would retreat to a tidy studio to paint. As his 1946 self-portrait The Artist at Work shows, he worked with the elbow of his painting arm resting in the cup of his other hand, which balanced on his crossed legs. He was methodical and meticulous, often considered part of the post-World War I Precisionism movement. With his hand steadied, he could be sure that every plane, clapboard and telephone wire was just so. “There’s always this sense of shaping, ordering, structuring as if his life depended on it,” says Nemerov.

When you take into account Ault’s tumultuous life, perhaps it did. After attending the University College School, the Slade School of Fine Art and St. John’s Wood Art School, all in London, in the early 1900s, the Cleveland native returned to the United States where he suffered a string of personal tragedies. In 1915, one of his brothers committed suicide. In 1920, his mother died in a mental hospital. And in 1929, his father died. The stock market crash dealt a hard blow to his family’s fortune, and his two other brothers took their lives soon after. Grieving his losses, the artist left Manhattan with Louise, whom he married in 1941, for Woodstock, where he lived until December 1948, when he too committed suicide, drowning in a stream near his house. As Louise once said, Ault’s art was an attempt to make “order out of chaos.”

Ault did not get much recognition during his lifetime, in part because of his reclusiveness and hostile attitude toward potential buyers. But Louise worked tirelessly to promote her husband’s work after his death. Of Ault’s paintings of Woodstock from the 1940s, she once wrote, “I believed he had gone beyond himself.”

Nemerov, guest curator of the exhibition, “To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s America,” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through September 5, agrees. He sees Ault as having painted clear and calm scenes in a desperate attempt to control the muddled chaos not only in his personal life but also in the world at large, on the verge of World War II. Written on the gallery wall at the entrance to the exhibition is the statement, “If the world was uncertain, at least the slope of a barn roof was a sure thing.”

For the exhibition, the first major retrospective of Ault’s work in more than 20 years, Nemerov, a former pre-doctoral fellow and research assistant at the museum, selected nearly 20 paintings by Ault as well as ones by his contemporaries, including Edward Hopper, Andrew Wyeth and Charles Sheeler. Together, the paintings offer a much more fragile, brooding view of the 1940s than do other cultural icons of the decade, such as J. Howard Miller’s poster We Can Do It! (better known as Rosie the Riveter), Alfred Eisenstaedt’s photograph V-J Day in Times Square and Bing Crosby’s recording of “Accentuate the Positive.” Ault’s paintings are quiet and subdued—a road rising over a grassy knoll, a white farmhouse in the shadows of looming gray clouds, and a barren view of the Catskills in November. “It’s almost as though his paintings expect nine out of ten people to walk past them,” says Nemerov. “But, of course, they are counting everything on that tenth person to notice them.” For that tenth person, argues Nemerov, Ault’s works carry emotion despite their lack of human figures and storytelling. Nemerov calls the waterfall in Ault’s Brook in the Mountains, for example, “a form of crying without crying,” adding that “emotion—painting from the heart—must for him take a curious and displaced form to be real, to be authentic.”

In her foreword to Nemerov’s exhibition catalog To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s America, Elizabeth Broun, director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, emphasizes how art provides a means of understanding what individual people were thinking and feeling in a particular time, in Ault’s case during the 1940s. “Their specific thoughts and emotions died with them,” she says, “but this exhibition and book delve below the surface of forty-seven paintings to understand the deeper currents below, helping us recapture some long-forgotten insight.”

In the exhibition are all five of Ault’s paintings of Russell’s Corners, including Bright Light at Russell’s Corners, the third in the series, which is part of the American Art Museum’s permanent collection. Four of the scenes are set at night, and having them all in the same gallery allows the viewer to see how the black sky in each becomes more dominant as the series progresses. Buildings, trees and telephone poles are illuminated by a single streetlight in the first couple of depictions, whereas in the last, August Night at Russell’s Corners, which Ault painted in his final year of life, the darkness consumes all but two shadowed faces of barns and a small patch of road, as if Ault is losing the tight hold he once had on the world.

“I couldn’t blame people for thinking this is an unduly dark show,” says Nemerov. Perhaps for that reason, the art historian clings to the recurring streetlight in the Russell’s Corners series. “That light represents something that is about delivery, revelation and pleasure,” he says. He suggests that the light could have a religious connotation. Its radiating beams are reminiscent of the light in Sassetta’s 15th- century painting The Journey of the Magi, a reproduction of which Ault kept in his studio. But because the artist was not a religious man, Nemerov considers the light a symbol of the ecstasy and exhilaration of an artistic act, a burst of creativity. After all, out of Ault’s turmoil came one glaringly positive thing: an impressive body of art. Quite fittingly, Louise used a quotation from the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche to describe her husband. “Unless there be chaos within, no dancing star can be born.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)