George Washington and Abigail Adams Get an Extreme Makeover

Conservators at the National Gallery Art restored Gilbert Stuart portraits of our founding figures, making them look good as new

![stewart_restauration-631x300[1].jpg](https://th-thumbnailer.cdn-si-edu.com/mGllMQY9W1IUTnalHOAUroeO_2Q=/1000x750/filters:no_upscale()/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/stewart_restauration-631x300%5B1%5D.jpg)

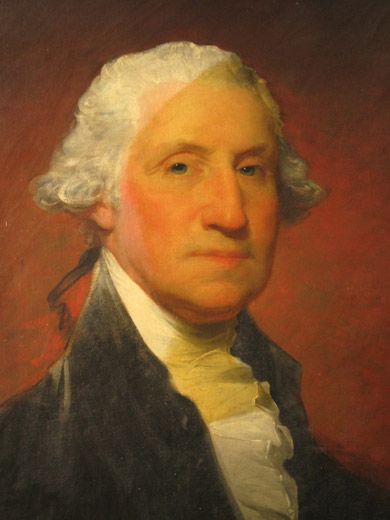

Inside the conservation lab at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. , Joanna Dunn painstakingly wipes a solvent-soaked cotton swab across the bridge of Joseph Anthony’s nose. Her subject, a prominent merchant at the outset of the American republic, stares out from a 1787 depiction by master portraitist Gilbert Stuart. The force of White’s gaze has been muted, its intensity obscured by a layer of hazy, yellowed varnish. As Dunn cleans the canvas, however, a transformation takes hold. “The varnish makes everything dull, and flat,” Dunn says. “When you get it off, you see all the subtle details—the ruddiness in his cheek, the twinkle in his eye—and he really comes to life.”

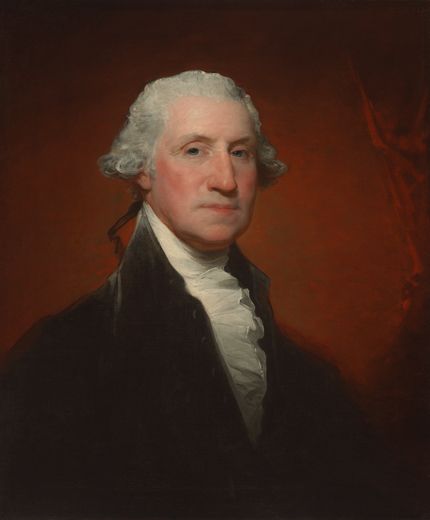

Dunn and her fellow conservators finished restoring 16 of the museum’s Stuart masterpieces to their original beauty. Seven newly refreshed works by Stuart, including depictions of George Washington, as well as John and Abigail Adams, are being unveiled this weekend, on October 7—the first time these works will be shown together in a pristine condition since their creation. (The National Gallery is home to a total of 42 Stuart portraits, including 13 others on permanent display.) In the country’s earliest days, Stuart rose from humble beginnings as the son of a snuff-maker to become our de facto portraitist laureate. The most distinguished statesmen, generals, and lawmakers lined up to sit for a portrait because of Stuart’s renowned ability to create deep, vibrant portrayals on a flat surface. In 1822, the Boston Daily Advertiser wrote about his series of the first five presidents, “Had Mr. Stuart never painted anything else, these alone would be sufficient to make his fame with posterity. No one…has ever surpassed him in fixing the very soul on canvas.”

These radiant souls, though, have had a way of fading over the years. In Stuart’s day, artists covered their paintings with protective varnishes—and though they appeared clear when first applied, the coatings inevitably yellowed due to a reaction with oxygen in the air. “Stuart really wanted his paintings to look fresh and bright,” Dunn says. “He hated to varnish them, because he knew they would turn yellow.” Nevertheless, he did anyway, and his works were gradually muted over time.

Now, as part of an ongoing project, conservators are using the latest techniques to show the portraits’ true colors. Applying a gentle solvent (one that that will remove varnish but not original paint), Dunn rolls a cotton swab across a small section of the canvas for hours at a time. Eventually, the varnish lifts off, exposing exquisite brushstrokes and vivid pigments. Dunn also removes discolored restoration paint—until the middle of the 20th century, restorers frequently added their own flourishes to historical works, creating color mismatches—and inpaints with her own. Unlike previous conservators, though, she is careful not to cover any of Stuart’s original work, meticulously introducing only a tiny dot of color-matched paint wherever bare canvas shows though. Finally, Dunn coats the piece with a new varnish, formulated to remain clear indefinitely. Spending hours face-to-face with these works, she develops a deep connection to her subjects. “I definitely get attached to the sitters,” she says. “I sometimes even invent little stories about them in my head while I’m working.”

Stuart had a talent for capturing the personalities of his sitters, a skill enabled by his habit of chatting and joking with them as he worked, rather than forcing them to sit perfectly still as many portraitists did in his day. “He always engaged his sitters in conversation, so he was able to relate to them, and reveal a little more about their character than any other painter was able to do,” says National Gallery curator Debra Chonder. “Looking at the portraits, you can almost tell when he was particularly engaged with someone.” The portrait of Abigail Adams, Dunn says, is a case in point: “He made her look like the intelligent, kind person that she was. In addition to the outer appearance of his subjects, he captures their inner beauty.”

The careful restoration of these works has even helped uncover previously unknown stories about their actual creation. For years, scholars were puzzled by an early copy of Stuart’s Abigail Adams portrait, made by another artist: It featured a cloth atop her head, instead of the white bonnet in Stuart’s version. Then, when conservator Gay Myers removed old restoration paint from the original, she discovered a similarly shaped patch above Adams’ head. Stuart, it turned out, had likely given Adams a head cloth to wear for modesty’s sake as she sat in 1800 and sketched it on the canvas; he replaced it with a bonnet that matched the latest fashions when he finally completed the painting in 1815.

All these years, a telling detail of Stuart’s creative process was hidden under a thin layer of paint. In revealing it, conservation does more than restore the art—it recreates the artist. “When you’re working on a portrait, you feel like you get to know the artist,” Dunn says. “You start to envision him creating the painting.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)