Get Your Game On

At the Smithsonian American Art Museum, tech-savvy players gather clues in the alternate reality game “Ghosts of a Chance”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/artofthegame_631.jpg)

It began with the man who would not talk about his tattoos.

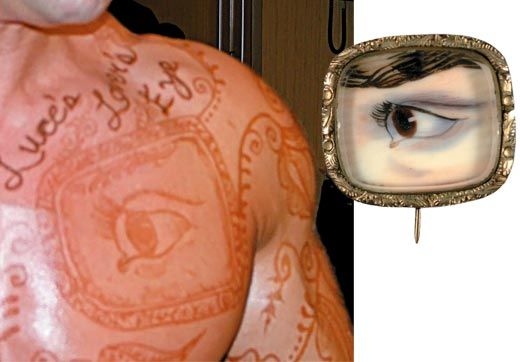

He walked bare-chested into an academic conference at the Radisson Hotel in Boston, dull red tattoos crawling all over his chest and arms. He circled the room, posing, for three minutes. Then without a word, he left.

The July 19 event was unusual even for people used to unusual happenings. The conference was ARGfest-o-Con 2008, and the 100 people there designed, played or studied alternate reality games (ARGs), in which players use clues from a variety of media to solve puzzles and participate via the Internet in an evolving story.

Although the attendees didn't realize it at the time, the tattooed man was the initial clue in the first-ever ARG sponsored by a major museum: the Smithsonian American Art Museum's "Ghosts of a Chance." Once word of the game spread, people all over the world logged on to Unfiction.com, a Web site where ARG players swap clues and speculate on a game's direction.

Using the search engine Google, a player found out that one of the man's tattoos, labeled "Luce's Lover's Eye," matched a painting at the museum's Luce Foundation Center for American Art. On the painting's Web page, a speech from Romeo and Juliet appeared. Clicking a link in the text led to GhostsofaChance.com. There, players were asked to call a phone number and record an incantation, the three witches' "toil and trouble" lines from Macbeth. For a few days, there were no clues—except for the site's countdown to September 8, the official start date.

In an ARG, initial clues can come from many sources, including a live event like the tattooed man's appearance, a video ad or even this magazine. Once the game is on, designers, called PuppetMasters, place clues in other forms of media such as posters, TV commercials and Web sites to attract a wider audience. Anyone can register to play, free, at Unfiction.com.

Invented in 2001 by a couple of tech wizards at Microsoft, ARGs usually last six to eight weeks and require lots of teamwork, if only because the obscure clues can be hidden in computer codes, foreign languages or complex riddles. The games have been used as viral marketing to promote TV shows, including "Alias" and "Lost," as well as the video game Halo 2.

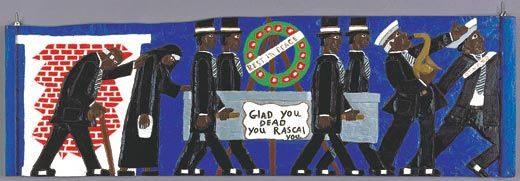

"Ghosts of a Chance" was designed by John Maccabee, a former novelist whose San Francisco-based company, CityMystery, specializes in the growing field of educational ARGs. In "Ghosts," the premise is that some of the artworks in the Luce Center collection have become haunted. Players have to find out who the ghosts are, which artworks are infected, and how to thwart the undead scourge and save the collection. Along the way, players will influence the story itself, either when Maccabee changes it in response to their Unfiction comments or through two nonvirtual events at which gamers interact with hired actors. "ARGs have beginnings, middles and ends, so they are real stories," Maccabee says. "But still the players are interacting with you and taking the game in a direction that they want to take it."

Museum officials see "Ghosts" as a new way to engage visitors. "People who are visiting museums now are looking for more than just going to a gallery and looking at the things on the wall," says Georgina Bath, the Luce Center's program coordinator. "The ARG is one way of creating a layer of interactivity in the space without putting the artworks at risk." ARGs might also attract young people who are less likely to go for the traditional museum experience. "I hope [players] see the museum as somewhere they can come back and spend more time," Bath says.

"One of the great things about ARGs is that they change a display space to an adventurous, active space," says veteran game designer Jane McGonigal, of the Institute for the Future, a nonprofit research center. Since people at a museum already share a common interest in the collection, she adds, the "seed of a community" exists.

The Luce Center plans to keep "Ghosts" around even after its grand finale on October 25. The museum has commissioned a version of the game that a group of visitors could play on-site in one afternoon.

McGonigal says ARGs work best when players solve real problems. That should bode well for ARGs based at museums, since, she adds: "Any museum is going to have some unsolved mysteries."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anika-gupta-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anika-gupta-240.jpg)