Gettysburg Address Displayed at Smithsonian

Lincoln’s timeless speech during the Civil War endures as a national treasure

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/objectathand_dec08_631.jpg)

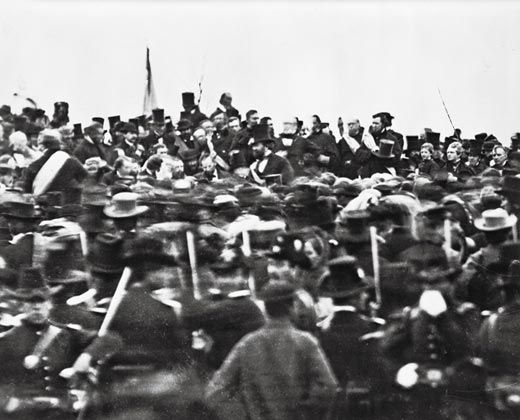

In American History, November 19, 1863, might be considered a day of wind and fire.

The place was the Gettysburg battlefield, four and a half months after the bloody and pivotal victory of the Union's Army of the Potomac over Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. The event was the dedication of a cemetery for those who had died on those rolling fields. The wind was a two-hour speech by Edward Everett, a renowned orator and former senator from Massachusetts. And the fire was a dedication by President Abraham Lincoln that followed, a speech hardly more than two minutes in length. Like an ember left over from the conflagration of battle, it has warmed the nation's collective memory ever since.

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address represents perhaps the perfect combination of eloquence, elegance and economy in our history, shining rhetorical proof of the design axiom, "Less is more." Given the florid oratorical standards of the time, Lincoln's brevity could hardly have been expected. Yet a more reverberant effect cannot be imagined. Harry Rubenstein, chair of the division of politics and reform at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History (NMAH), sums up the occasion nicely: "Everybody says the same thing about the ceremony: Lincoln gave a great speech and Everett spoke for two hours."

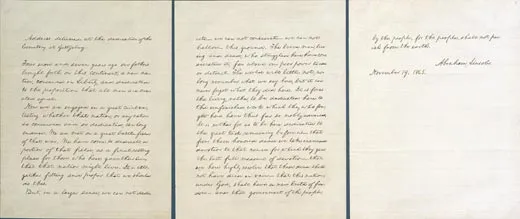

A copy of that speech, in Lincoln's handwriting—the version generally regarded as the definitive text—is now on loan from the White House, displayed in the new Albert H. Small Documents Gallery at the reopened NMAH. It will be on view through January 4.

American schoolchildren have learned its cadences by heart for decades; many of us, young and nervous, recited it at patriotic ceremonies as our parents, proud and nervous, looked on. But the venerated address was not universally admired at the time. Eyewitnesses reported that there was silence when Lincoln finished, followed by sparse applause, once described by the late historian Shelby Foote as "barely polite."

It's possible that so soon after it began, hardly anyone realized that the speech had ended. Nor was the elegiac tone so appropriate to the occasion calculated to elicit the applause lines that presidential speechwriters seek today. It may seem surprising, too, that Everett, not the president, was the main speaker of the day. According to Rubenstein, the orator's top billing "made sense at the time. You're not going to ask a president in the middle of a major war to take the time to write a big speech."

The Chicago Times, no friend of Lincoln's, described the address as "silly, flat and dishwatery utterances," while the New York Times, strongly Republican at the time, praised it. The president himself is said to have harbored doubts about the speech. Everett was gracious. "I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes," he wrote to Lincoln the day after the ceremony. Rubenstein says it's possible that Everett was merely being polite, "but there's no way to know."

Lincoln later sent his fellow speaker a copy of the speech when Everett was assembling a book listing events at the battlefield dedication, to be sold for the benefit of wounded Union soldiers. The president wrote out by hand five copies of the address, two before the ceremony—historians aren't sure which of these is the copy from which Lincoln read at Gettysburg—and three afterward.

Lincoln's last handwritten copy, the only one signed by the president, was penned in March 1864, to be reproduced for a publication entitled Autograph Leaves of Our Country's Authors, which was also intended to raise money for the Union cause. One of the book's publishers, Alexander Bliss, kept the original document; it's the one now on display at the NMAH.

This copy remained in the hands of the Bliss family until Oscar Cintas, Cuba's ambassador to the United States in the 1930s, bought it at auction in 1949 for $54,000 (roughly the cost of a substantial New York suburban house at the time). Cintas, who died in 1957, had willed the copy to the United States. It is usually displayed in the Lincoln bedroom of the White House. The brief dedication made at Gettysburg, says Rubenstein, endures as nothing less than "a remarkable piece of literature."

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)