Glimpses of the Lost World of Alchi

Threatened Buddhist art at a 900-year-old monastery high in the Indian Himalayas sheds light on a fabled civilization

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Alchi-goddess-Tara-631.jpg)

The wood-framed door is tiny, as if intended for a Hobbit, and after I duck through it into the gloomy interior—dank and perfumed with the saccharine scent of burnt butter oil and incense—my eyes take a while to adjust. It takes my mind even longer to register the scene before me.

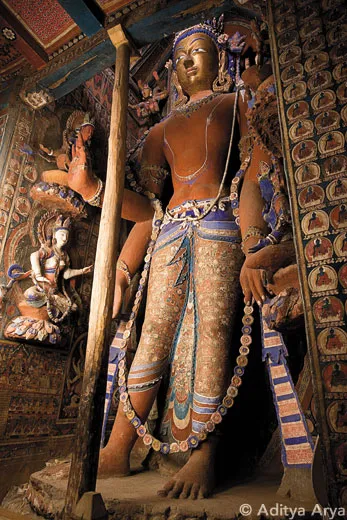

Mesmerizing colored patterns scroll across the wood beams overhead; the temple’s walls are covered with hundreds of small seated Buddhas, finely painted in ocher, black, green, azurite and gold. At the far end of the room, towering more than 17 feet high, stands an unblinking figure, naked to the waist, with four arms and a gilded head topped with a spiked crown. It’s a painted statue of the Bodhisattva Maitreya, a messianic being of Tibetan Buddhism come to bring enlightenment to the world. Two hulking statues, one embodying compassion and the other wisdom, stand in niches on side walls, attended by garishly colored sculptures depicting flying goddesses and minor deities. Each massive figure wears a dhoti, a kind of sarong, embellished with minutely rendered scenes from the life of Buddha.

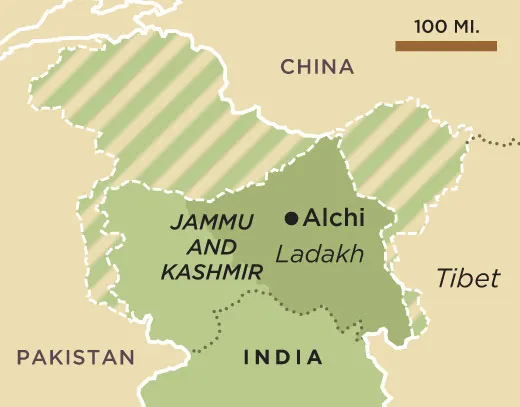

These extraordinary figures have graced this small monastery in Alchi, a hamlet high in the Indian Himalayas along the border with Tibet, for about 900 years. They are among the best-preserved examples anywhere of Buddhist art from this period, and for three decades—since the Indian government first allowed foreign visitors to the region—scholars have been trying to unlock their secrets. Who created them? Why don’t they conform to orthodox Tibetan Buddhist conventions? Might they hold the key to rediscovering a lost civilization that once thrived, more than a hundred miles to the west, along the Silk Road?

The monastery and its paintings are in grave danger. Rain and snowmelt have seeped into temple buildings, causing mud streaks to obliterate portions of the murals. Cracks in clay-brick and mud-plaster walls have widened. The most pressing threat, according to engineers and conservators who have assessed the buildings, is a changing climate. The low humidity in this high-altitude desert is one reason Alchi’s murals have survived for almost a millennium. With the onset of warmer weather in the past three decades, their deterioration has accelerated. And the possibility that an earthquake could topple the already fragile structures, located in one of the world’s most seismically active regions, remains ever-present.

The Alchi murals, their vibrant colors and beautifully rendered forms rivaling medieval European frescoes, have drawn a growing number of tourists from around the world; conservationists worry the foot traffic may take a toll on ancient floors, and the water vapor and carbon dioxide the visitors exhale may hasten the paintings’ decay.

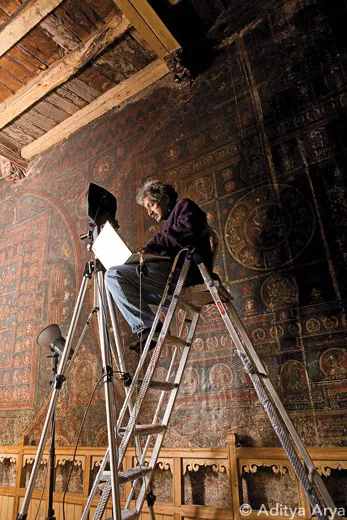

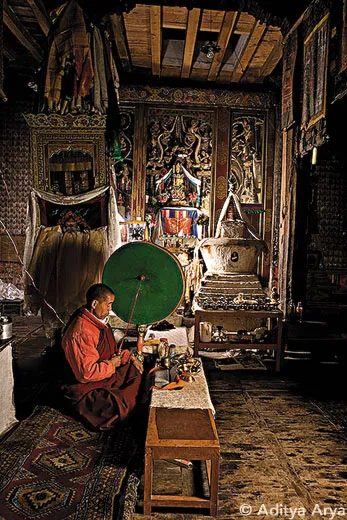

Two years ago, an Indian photographer, Aditya Arya, arrived in Alchi to begin documenting the monastery’s murals and statues before they disappear. A commercial and advertising photographer best known for shooting “lifestyle” pictures for glossy magazines and corporate reports, he once shot stills for Bollywood film studios. In the early 1990s, he was an official photographer for Russia’s Bolshoi Ballet.

But Arya, 49, who studied history in college, has always harbored a more scholarly passion. He photographed life along the Ganges River for six years, in a project that became a book, The Eternal Ganga, in 1989. For a 2004 book, The Land of the Nagas, he spent three years chronicling the ancient folkways of Naga tribesmen in northeast India. In 2007, he traveled throughout India to photograph sculpture from the subcontinent’s Gupta period (fourth to eighth centuries A.D.) for India’s National Museum. “I think photographers have a social responsibility, which is documentation,” he says. “[It] is something you can’t shirk.”

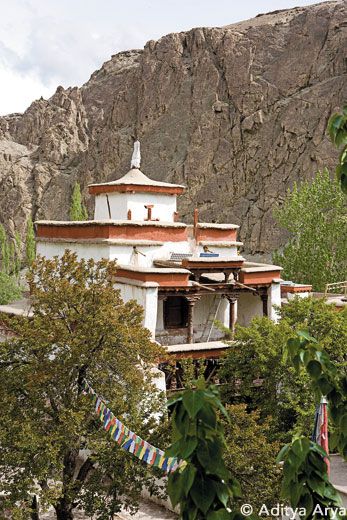

Alchi lies 10,500 feet up in the Indian Himalayas, nestled in a crook alongside the cold jade waters of the Indus River, sandwiched between the snowy peaks of the Ladakh and Zanskar mountains. From a point on the opposing bank, Alchi’s two-story white stucco buildings and domed stupas resemble a crop of mushrooms sprouting from a small, verdant patch amid an otherwise barren landscape of rock, sand and ice.

Getting here entails flying from New Delhi to the town of Leh, sited at an altitude of more than 11,000 feet, followed by a 90-minute drive along the Indus River valley. The journey takes you past the camouflaged barracks of Indian Army bases, past the spot where the blue waters of the Zanskar River mingle with the Indus’ mighty green and past a 16th-century fort built into cliffs above the town of Basgo. Finally, you cross a small trellis bridge suspended above the Indus. A sign hangs over the road: “The model village of Alchi.”

Several hundred inhabitants live in traditional mud and thatch houses. Many women wearing customary Ladakhi pleated robes (gonchas), brocaded silk capes and felt hats work in the barley fields and apricot groves. A dozen or so guesthouses have sprung up to cater to tourists.

Alchi’s status as a backwater, located on the opposite bank of the Indus from the routes invading armies traveled in the past and commercial truckers use today, has helped preserve the murals. “It is a kind of benign neglect,” says Nawang Tsering, head of the Central Institute of Buddhist Studies, based in Leh. “Alchi was too small, so [the invaders] didn’t touch it. All the monasteries along the highway were looted hundreds of times, but Alchi nobody touched.”

Although Alchi’s existence is popularly attributed to Rinchen Zangpo, a translator who helped promulgate Buddhism throughout Tibet in the early 11th century, most scholars believe the monastic complex was founded nearly a century later by Kalden Sherab and Tshulthim O, Buddhist priests from the region’s powerful Dro clan. Sherab studied at Nyarma Monastery (which Zangpo had founded), where, according to an inscription in Alchi’s prayer hall, “like a bee, he gathered the essence of wise men’s thoughts, which were filled with virtue as a flower is with nectar.” As a member of a wealthy clan, Sherab likely commissioned the artists who painted Alchi’s oldest murals.

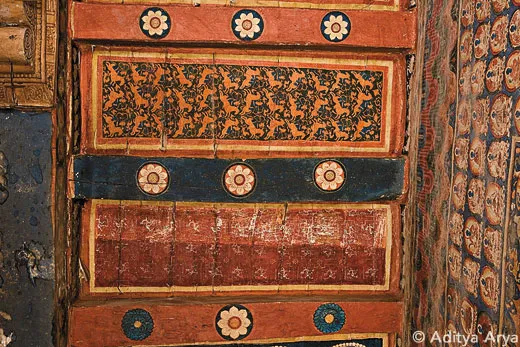

Who were these artists? The Dukhang, or Assembly Hall, contains a series of scenes depicting nobles hunting and feasting at a banquet. Their dress—turbans and tunics adorned with lions—and braided hair appear Central Asian, perhaps Persian. The colors and style of painting are not typically Tibetan. Rather, they seem influenced by techniques from as far west as Byzantium. The iconography found in some of the Alchi murals is also highly unusual, as is the depiction of palm trees, not found within hundreds of miles. And there are the geometric patterns painted on the ceiling beams of the Sumtsek (three-tiered) temple, which scholars suspect were modeled on textiles.

Many scholars theorize that the creators of the Alchi murals were from the Kashmir Valley in the west, a 300-mile journey. And though the temple complex was Buddhist, the artists themselves may have been Hindus, Jains or Muslims. This might explain the murals’ arabesques, a design element associated with Islamic art, or why people depicted in profile are painted with a protruding second eye, a motif found in illuminated Jain manuscripts. To reach Alchi, the Kashmiris would have journeyed for weeks on foot through treacherous mountain passes. Because of stylistic similarities, it is thought that the same troupe of artists may have painted murals in other monasteries in the region.

If the artists were Kashmiri, Alchi’s importance would be even greater. In the eighth and ninth centuries, Kashmir emerged as a center of Buddhist learning, attracting monks from throughout Asia. Though Kashmir’s rulers soon reverted to Hinduism, they continued to tolerate Buddhist religious schools. By the late ninth and tenth centuries, an artistic renaissance was underway in the kingdom, fusing traditions of East and West and borrowing elements from many religious traditions. But few artifacts from this remarkably cosmopolitan period survived Kashmir’s Islamic sultanate in the late 14th century and the subsequent 16th-century Mogul conquest of the valley.

Alchi may provide crucial details about this lost world. For instance, the dhoti on one colossal statue—the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, who embodies compassion—is decorated with unknown temples and palaces. British anthropologist David Snellgrove and German art historian Roger Goepper have postulated that the images depict actual places in Kashmir—either ancient pilgrimage sites or contemporary buildings the artists knew. Because no large Kashmiri wooden structures from this period survive, Avalokiteshvara’s dhoti may provide our only glimpse of the architecture of 12th-century Kashmir. Similarly, if the patterns painted on the Sumtsek beams are in fact designed to mimic cloth, they may constitute a veritable catalog of medieval Kashmiri textiles, of which almost no actual examples have been preserved.

Researchers aren’t sure why the temples were built facing southeast, when Buddhist temples customarily face east, as the Buddha was said to have done when he found enlightenment. Nor is it known why the image of the Buddhist goddess Tara—a green-skinned, many-armed protector—was accorded such prominence in the Sumtsek paintings. Much about Alchi remains baffling.

Although it is late spring, a numbing chill pervades Alchi’s Assembly Hall. Standing in its dark interior, Arya lights a small stick of incense and makes two circuits around the room before placing the smoldering wand on a small altar. Only after performing this purification ritual does he return to his camera. Arya is Hindu, though not “a hard-core believer,” he says. “I must have done something seriously good in my past life, or seriously bad, because I wind up spending so much of my life in these temples.”

He first came to Ladakh in 1977, to explore the mountains, shortly after tourists were first permitted to travel here. He later led treks through the area as a guide and photographer for a California-based adventure travel outfit.

For this assignment, he has brought an ultra-large-format digital camera that can capture an entire mandala, a geometric painting meant to depict the universe, in exquisite detail. His studio lights, equipped with umbrella-shaped diffusers to avoid damaging the paintings, are powered by a generator at a nearby guesthouse; the cord runs from the house down a narrow, dirt lane to the monastery. When the generator fails—as it often does—Arya and his two assistants are plunged into darkness. Their faces illuminated only by the glow of Arya’s battery-powered laptop computer, they look like ghosts from a Tibetan fable.

But when the studio lights are working, they cast a golden glow on the Assembly Hall’s mandalas, revealing stunning details and colors: the skeletal forms of Indian ascetics, winged chimeras, multi-armed gods and goddesses, and nobles on horseback hunting lions and tigers. Sometimes these details astound even Alchi’s caretaker monk, who says he has never noticed these facets of the paintings before.

The concern about conserving Alchi’s murals and buildings is nothing new. “A project for renovation and maintenance appears to be urgently called for,” Goepper wrote in 1984. Little has changed.

In 1990, Goepper, photographer Jaroslav Poncar and art conservators from Cologne, Germany, launched the Save Alchi Project. They catalogued damage to its paintings and temple buildings—some portions of which were even then in danger of collapsing—and began restoration work in 1992. But the project ended two years later, the victim, Goepper wrote, of what he termed “growing confusion over administrative responsibility.” Or, say others, between religious and national interests.

Although tourists now far outnumber worshipers, Alchi is still a living temple under religious control of the nearby Likir Monastery, currently headed by the Dalai Lama’s younger brother, Tenzin Choegyal. Monks from Likir serve as Alchi’s caretakers, collecting entrance fees and enforcing a prohibition on photography inside the temples. (Arya has special permission.) At the same time, responsibility for preserving Alchi as a historic site rests with the government’s Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

Relations between the ASI and the Likir monks have long been fraught. The monks are wary of government intrusion into religious matters; the ASI worries the monks will undertake restorations that damage the Alchi murals. The result is a stalemate that has thwarted conservation efforts, going back to Goepper’s.

The complex history of India’s Tibetan Buddhist refugees also factors into the impasse. In the 1950s, a newly independent India sheltered Tibetans fleeing China’s invasion of their homeland, including, eventually, the Dalai Lama, Tibetan Buddhism’s religious leader as well as the head of Tibet’s government. He established a government-in-exile in the Indian city of Dharamsala, a 420-mile drive from Alchi. At the same time, exiled Tibetan lamas were placed in charge of many of India’s most important Buddhist monasteries. The lamas have been vocal in support of a free Tibet and critical of China. Meanwhile, the Indian government, which is seeking better relations with China, views India’s Tibetan-Buddhist leaders and political activists, to some extent, as an annoyance.

Not long after arriving in Alchi to make photographs, Arya got a taste of the political conflict. One afternoon a local ASI official arrived at the monastery and demanded to see his authorization to photograph the murals. Apparently not satisfied with the documents (from Likir and the Central Institute of Buddhist Studies) that Arya produced, the official returned the next day and began to photograph the photographer. He told him that he planned to make a “report” to his superiors.

The encounter unnerved Arya. He considered suspending work on the project before deciding it was too important to abandon. “If tomorrow something would happen here, some earthquake or natural disaster, there will be nothing left,” he told me.

In fact, powerful tremors had rattled the ancient temple complex about the time Arya arrived—the result of blasting a little more than a mile from Alchi, where a dam is being constructed across the Indus as part of a major hydroelectric project. The dam project is popular. It has provided jobs to villagers and also promises to turn Ladakh, which has had to import electricity from other parts of India, into an energy exporter.

Despite ASI assurances that the blasting will not harm the ancient site, many worry it may undermine temple foundations. Manshri Phakar, an authority on hydroelectric projects with the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People, an environmental group based in New Delhi, says he has documented houses that have suffered damage, and even collapsed, because of blasting associated with dam construction elsewhere in India. He also notes that building a dam just upstream from the monastery in a seismically active region poses extra risks; should the dam fail, Alchi could be catastrophically flooded.

“India has been gifted with so much art and so much history that we have lost our ability to recognize and appreciate it,” Arya says. The Indian government “must take the risk of documentation”—the risk being that his photographs may encourage more tourism.

Arya would like to see his work displayed in a small museum at Alchi, along with written explanations of the monastery and its history. The monks, who sell postcards, give impromptu tours and have built a guesthouse for tourists, have been cool to that idea. “You have to understand that Alchi is not a museum,” says Lama Tsering Chospel, the spokesman for Likir. “It’s a temple.”

Fifteen miles from Alchi is an example of a successful melding of tourism and conservation. In Basgo, a town on the Indus that was once the capital of Ladakh, three ancient Buddhist temples and a fort have been renovated through a village cooperative, the Basgo Welfare Committee. As in Alchi, the Basgo temples are considered living monasteries—in this case under the religious jurisdiction of Hemis, like Likir, a major Tibetan Buddhist “mother church.” But in Basgo, the Hemis monastery, the ASI and international conservation experts have cooperated to save the endangered heritage. The project has received support from the New York-based World Monuments Fund as well as global art foundations. International experts have trained Basgo’s villagers in conservation methods using local materials, such as mud brick and stone-based pigments.

Basgo’s villagers understand the link between preserving the buildings and the local economy. “The survival of the town depends on tourism,” says Tsering Angchok, the engineer who serves as secretary of the Basgo Welfare Committee. “Really, if tourism is lost, everything is lost.”

In 2007 Unesco presented the Basgo Welfare Committee its award of excellence for cultural-heritage conservation in Asia. But Alchi’s monks have shown little interest in adopting the Basgo model. “What purpose will that serve?” Chospel asks.

Jaroslav Poncar says that the Alchi monks’ ambivalence can be traced to the paintings’ strong Kashmiri influence and to their distance from contemporary Tibetan Buddhist iconography. “It is cultural heritage, but it is not their cultural heritage,” says Poncar. “It is totally alien to their culture. For a thousand years, their emphasis has been on the creation of new religious art and not to preserve the old.”

Arya stands on a ladder peering into the viewfinder of his large-format camera. It is here on the Sumtsek’s normally off-limits second floor that acolytes training to be monks would have advanced after having studied the massive bodhisattvas on the ground floor. No longer focused on depictions of the physical world, they would have spent hours sitting in front of these mandalas, reciting Buddhist sutras and learning the philosophical concepts each mandala embodied. They would study the images until they could see them in their minds without any visual aids.

Bathed in the warm glow of his studio lights, Arya, too, focuses intensely on the mandalas. He presses the shutter cable on his camera—there is a pop, a sudden flash and the room goes dark; the generator has blown again and all that remains of Alchi’s technicolored wonders is the impression left on my retina, quickly fading. I am not a trained monk, and I cannot summon the mandala in my mind’s eye. Then, glancing down, I see it again, a perfect image shining from the screen of Arya’s battery-operated laptop—an image that will remain even if Alchi does not.

Writer and foreign correspondent Jeremy Kahn and photographer Aditya Arya are both based in New Delhi.