Going Mad for Charles Dickens

Two centuries after his birth, the novelist is still wildly popular, as a theme park, a new movie and countless festivals attest

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Charles-Dickens-Dickens-World-631.jpg)

In an abandoned Gillette razor factory in Isleworth, not far from Heathrow Airport, the British film director Mike Newell wades ankle-deep through mud. The ooze splatters everybody: the 100 or so extras in Victorian costume, the movie’s lead characters, the lighting engineers perched in cranes above the set. Newell is ten days into shooting the latest adaptation of Great Expectations, widely regarded as the most complex and magisterial of Charles Dickens’ works. To create a replica of West London’s Smithfield Market, circa 1820, the set-design team sloshed water across the factory floor—which had been jackhammered down to dirt during a now-defunct redevelopment project—and transformed the cavernous space into a quagmire.

Dickens completed Great Expectations in 1861, when he was at the height of his powers. It’s a mystery story, a psychodrama and a tale of thwarted love. At its center looms the orphaned hero Pip, who escapes poverty thanks to an anonymous benefactor, worships the beautiful, cold-hearted Estella and emerges, after a series of setbacks, disillusioned but mature. In the scene that Newell is shooting today, Pip arrives by carriage in the fetid heart of London, summoned from his home in the Kent countryside by a mysterious lawyer, Jaggers, who is about to take charge of his life. Newell leans over a monitor as his assistant director cries, “Roll sound, please!” Pause. “And action.”

Instantly the market comes alive: Pickpockets, urchins and beggars scurry about. Butchers wearing blood-stained aprons haul slabs of beef from wheelbarrows to their stalls past a pen filled with bleating sheep. Cattle carcasses hang from meat hooks. Alighting from a carriage, the disoriented protagonist, portrayed by Jeremy Irvine, collides with a neighborhood tough, who curses and pushes him aside. “Cut,” Newell shouts, with a clap of his hands. “Well done.”

Back in his trailer during a lunch break, Newell, perhaps best known for Four Weddings and a Funeral and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, tells me that he worked hard at capturing the atmospherics of Smithfield Market. “Victorian London was a violent place. Dickens deliberately set the scene in Smithfield, where animals got killed in [huge] numbers every day,” he says. “I remember a paragraph [he wrote] about the effluence of Smithfield, about blood and guts and tallow and foam and piss and God-knows-what-else. And then this boy comes off the Kentish marshes, where everything looks peaceful, and he’s suddenly put into this place of enormous violence and cruelty and stress and challenge. That’s what Dickens does, he writes very precisely that.”

Scheduled for release this fall, the film—which stars Ralph Fiennes as the escaped convict Magwitch, Helena Bonham Carter as Miss Havisham and Robbie Coltrane as Jaggers—is the most recent of at least a dozen cinematic versions. Memorable adaptations range from David Lean’s 1946 black-and-white masterpiece starring Alec Guinness, to Alfonso Cuarón’s steamy 1998 reinterpretation, with Gwyneth Paltrow, Ethan Hawke and Robert De Niro, set in contemporary New York City. Newell, who became entranced with Dickens as an undergraduate at Cambridge, leapt at the opportunity to remake it. “It is a great, big powerhouse story,” he tells me. “And it has always invited people to bring their own nuances to it.”

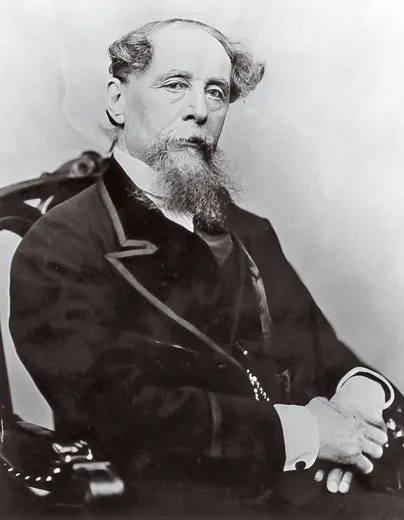

Dickens burst onto the London literary scene at age 23, and as the world celebrates his 200th birthday on February 7, “The Inimitable,” as he called himself, is still going strong. The writer who made the wickedness, squalor and corruption of London his own, and populated its teeming cityscape with rogues, waifs, fools and heroes whose very names—Quilp, Heep, Pickwick, Podsnap, Gradgrind—seem to burst with quirky vitality, remains a towering presence in culture both high and low. In December 2010, when Oprah Winfrey’s monthly book club selected A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations, publishers rushed 750,000 copies of a combined edition into print. (Sales were disappointing, however, in part because Dickens fans now can download the novels on e-readers free.) The word “Dickensian” permeates our lexicon, used to evoke everything from urban squalor to bureaucratic heartlessness and rags-to-riches reversals. (“No Happy Ending in Dickensian Baltimore” was the New York Times headline on a story about the final season of HBO’s “The Wire.”) Collectors snap up Dickens memorabilia. This past October, a single manuscript page from his book The Pickwick Papers—one of 50 salvaged in 1836 by printers at Bradbury and Evans, Dickens’ publisher—was sold at auction for $60,000.

Celebrations of the Dickens bicentenary have rolled out in 50 countries. Dickens “saw the world more vividly than other people, and reacted to what he saw with laughter, horror, indignation—and sometimes sobs,” writes Claire Tomalin in Charles Dickens: A Life, one of two major biographies published in advance of the anniversary. “[He] was so charged with imaginative energy...that he rendered nineteenth-century England crackling, full of truth and life.”

In New York City, the Morgan Library—which has amassed the largest private collection of Dickens’ papers in the United States, including the manuscript of A Christmas Carol, published in 1843—has organized an exhibition, “Charles Dickens at 200.” The show recalls not only the novelist, but also the star and director of amateur theatricals, the journalist and editor, the social activist and the ardent practitioner of mesmerism, or hypnosis. There’s a Dickens conference in Christchurch, New Zealand; “the world’s largest Dickens festival” in Deventer, the Netherlands; and Dickens readings from Azerbaijan to Zimbabwe.

London, the city that inspired his greatest work, is buzzing with museum exhibitions and commemorations. In Portsmouth, where Dickens was born, events are being staged thick and fast—festivals, guided walks, a reading of A Christmas Carol by great-great-grandson Mark Dickens—although the novelist left the city when he was 2 years old and returned there only three times. Fiercely protective of its native son, Portsmouth made headlines this past autumn when its libraries at last rescinded an eight-decade ban on a 1928 novel, This Side Idolatry, which focused on darker elements of Dickens’ character—including his philandering. Rosalinda Hardiman, who oversees the Charles Dickens’ Birthplace Museum, told me, “Feelings still run high about Dickens’ memory in the city of his birth. Some people don’t like the idea that their great writer was also a human being.”

Charles John Huffam Dickens was born in a modest four-story house, now the museum. Dickens’ father, John, was a likable spendthrift who worked for the Naval Pay Office; his mother, born Elizabeth Barrow, was the daughter of another naval employee, Charles Barrow, who fled to France in 1810 to escape prosecution for embezzling. The Dickens family was forced to move frequently to avoid debt collectors and, in 1824, was engulfed by the catastrophe that has entered Dickens lore: John was arrested for nonpayment of debts and jailed at Marshalsea prison in London. He would serve as the model for both the benevolently feckless Mr. Micawber in David Copperfield and William Dorrit, the self-delusional “Father of the Marshalsea,” in the later novel Little Dorrit.

With his father incarcerated, Charles, a bright and industrious student, was forced to leave school at around age 11 and take a job gluing labels on bottles at a London bootblacking factory. “It was a terrible, terrible humiliation,” Tomalin told me, a trauma that would haunt Dickens for the rest of his life. After John Dickens was released from jail, the son resumed his education; neither parent ever mentioned the episode again. Although Charles immortalized a version of the experience in David Copperfield, he himself disclosed the interlude perhaps only to his wife, and later, to his closest friend, the literary critic and editor John Forster. Four years after the novelist’s death, Forster revealed the incident in his Life of Charles Dickens.

At 15, with his father again insolvent, Dickens left school and found work as a solicitor’s clerk in London’s Holburn Court. He taught himself shorthand and was hired by his uncle, the editor of a weekly newspaper, to transcribe court proceedings and eventually, debates at the House of Commons, a difficult undertaking that undoubtedly sharpened his observational powers. In a new biography, Becoming Dickens, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst describes the rigors of the task: “Cramped, gloomy, and stuffy, [the Parliamentary chamber] required the reporter to squeeze himself onto one of the benches provided for visitors, and then balance his notebook on his knees while he strained to hear the speeches drifting up from the floor.” Soon Dickens was working as a political reporter for the Morning Chronicle and writing fictional sketches for magazines and other publications under the pen name Boz. Dickens parlayed that modest success into a contract for his first novel: a picaresque, serialized tale centering on four travelers, Samuel Pickwick, Nathaniel Winkle, Augustus Snodgrass and Tracy Tupman—the Pickwick Society— journeying by coach around the English countryside.The first installment of The Pickwick Papers appeared in April 1836, and the monthly print run soared to 40,000. In November, Dickens quit the newspaper to become a full-time novelist. By then he had married Catherine Hogarth, the pleasant, if rather passive, daughter of a Morning Chronicle music critic.

In the spring of 1837, the newly famous, upwardly mobile Dickens moved into a four-story Georgian town house in the Bloomsbury neighborhood at 48 Doughty Street with his wife, their infant son, Charles Culliford Boz Dickens, and Catherine’s teenage sister, Mary Hogarth.The property since 1925 has been the site of the Charles Dickens Museum, stocked with period furniture and art, as well as memorabilia donated by Dickens’ descendants. When I arrived a few months ago, a crew was breaking through a wall into an adjacent house to create a library and education center. Director Florian Schweizer guided me past divans and paintings shrouded in dust covers. “It probably looks the way it did when Dickens was moving in,” he told me.

The two and a half years that the Dickenses spent on Doughty Street were a period of dazzling productivity and dizzying social ascent. Dickens wrote an opera libretto, the final chapters of The Pickwick Papers, short stories, magazine articles, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickelby and the beginning of Barnaby Rudge. Shadowed by his father’s failures, Dickens had lined up multiple contracts from two publishers and “was trying to make as much money as he could,” Schweizer says as we pass a construction crew en route to the front parlor. “His great model, Walter Scott, at one point had lost all his money, and he thought, ‘This could happen to me.’” Dickens attracted a wide circle of artistic friends and admirers, including the most famous English actor of the time, William Macready, and the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, also an accomplished draftsman, who would later apply—unsuccessfully—for the job of illustrating Dickens’ works. Portraits of Dickens painted during the years at Doughty Street depict a clean-shaven, long-haired dandy, typical of the Regency period before the reign of Queen Victoria. “He dressed as flamboyantly as he could,” says Schweizer, “with jewelry and gold everywhere, and bright waistcoats. To our eyes he looked quite effeminate, but that’s how ‘gents’ of the time would have dressed.”

Schweizer and I mount a creaking flight of stairs to the second floor and enter Dickens’ empty study. Each day, Dickens wrote from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. at a large wooden desk in this room, with views of the mews and gardens, and with the morning sun streaming through the windows. But Dickens’ contentment here was short-lived: In the summer of 1837, his beloved sister-in-law Mary Hogarth collapsed at home, perhaps of heart failure. “A period of happiness came to an abrupt end,” says Schweizer, leading me up to the third-floor bedroom where the 17-year-old died in Dickens’ arms.

Dickens, although devastated by the loss, continued writing. The huge success of Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickelby, both released in serial form, made Dickens arguably the most famous man in England. As always, he forged the material of his life into art: In The Old Curiosity Shop, completed in 1841, Dickens transmuted his memories of Mary Hogarth into the character of the doomed Little Nell, forced to survive in the streets of London after the wicked Quilp seizes her grandfather’s shop. His melodramatic account of her lingering final illness distressed readers across all classes of British society. “Daniel O’Connell, the Irish M.P., reading the book in a railway carriage, burst into tears, groaned ‘He should not have killed her’, and despairingly threw the volume out of the train window,” Edgar Johnson writes in his 1976 biography, Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph.

In January 1842, at the height of his fame, Dickens decided to see America. Enduring a stormy crossing aboard the steamer Britannia, he and Catherine arrived in Boston to a rapturous welcome. Readings and receptions there, as well as in Philadelphia and New York, were mobbed; Dickens calculated that he must have shaken an average of 500 hands a day. But a White House meeting with President John Tyler (dubbed “His Accidency” by detractors because he took office after the sudden death of his predecessor) left the novelist unimpressed. He was disgusted by the state of America’s prisons and repelled by slavery. “We are now in the regions of slavery, spittoons, and senators—all three are evils in all countries,” Dickens wrote from Richmond, Virginia, to a friend. By the end of the odyssey, he confided that he had never seen “a people so entirely destitute of humor, vivacity, or the capacity for enjoyment. They are heavy, dull, and ignorant.” Dickens recast his American misadventure in Martin Chuzzlewit, a satirical novel in which the eponymous hero flees England to seek his fortune in America, only to nearly perish of malaria in a swampy, disease-ridden frontier settlement named Eden.

I’m huddled in a plastic poncho aboard a skiff in the sewers of 19th-century London. Peering through darkness and fog, I float past water wheels, musty back alleys, the stone walls of the Marshalsea debtors’ prison, dilapidated tenements, docks and pilings. Rats skitter along the water’s edge. I duck my head as we pass beneath an ancient stone bridge and enter a tunnel. Leaving the sewers behind, the boat begins to climb at a sharp angle, improbably emerging onto the East End’s rooftops—strung with lines of tattered laundry, against a backdrop of St. Paul’s Cathedral silhouetted in the moonlight. Suddenly, the skiff catapults backward with a drenching splash into a graveyard, pulling to a stop in the marshes of Kent, where the fugitive Magwitch fled at the outset of Great Expectations.

In fact, I’m inside a sprawling structure near a shopping mall in Chatham, in southeastern England, at one of the more kitschy manifestations of Charles Dickens’ eternal afterlife. Dickens World, a $100 million indoor theme park dedicated to Britain’s greatest novelist, opened in 2007, down the road from the former Royal Naval Shipyard, now the Chatham Maritime, where John Dickens worked after being transferred from Portsmouth, in 1821. Dickens World attracts tens of thousands of visitors annually—many of them children on school trips organized by teachers hoping to make their students’ first exposure to Dickens as enjoyable as a trip to Disneyland.

A young marketing manager leads me from the Great Expectations Boat Ride into a cavernous mock-up of Victorian London, where a troupe of actors prepares for a 15-minute dramatization of scenes from Oliver Twist. Past Mrs. Macklin’s Muffin Parlor—familiar to readers of Sketches by Boz—and the cluttered shop of Mr. Venus, the “articulator of human bones” and “preserver of animals and birds” from Our Mutual Friend, we enter a gloomy manse. Here, in rooms off a dark corridor, holograms of Dickens characters—Miss Havisham, Oliver Twist’s Mr. Bumble the Beadle, Tiny Tim Cratchet, Stony Durdles from The Mystery of Edwin Drood—introduce themselves in the voice of Gerard Dickens, Charles’ great-great-grandson. My tour concludes in the Britannia Theatre, where an android Dickens chats with a robotic Mr. Pickwick and his servant, Samuel Weller.

When Dickens World opened, it ignited a fierce debate. Did the park trivialize the great man? A critic for the Guardian scoffed that Dickens World perpetrated a “taming of the wildness and fierceness of Dickens” and had replaced his dark, violent London with a “Disney-on-Sea instead, a nice, safe, cosy world where nothing bad occurs.” Florian Schweizer of the Dickens Museum has a mixed response: “They’ve done a good job for their audience,” he told me. “If that means, in a generation or two, people will go back and say, ‘My first memory of Dickens was Dickens World, and I got hooked,’ then great. If people say, ‘I remember this, and never touched a Dickens novel,’ then it hasn’t worked.” But Kevin Christie, a former producer for 20th Century Fox who worked with conceptual architect Gerry O’Sullivan-Beare to create Dickens World, told me that “Dickens was a showman of the first order, and I think he would have loved this.”

By the time Dickens published Great Expectations in 1861, his public and private lives had diverged. The literary world lionized him. Ralph Waldo Emerson, who attended one of Dickens’ readings in Boston, called his genius “a fearful locomotive.” Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who had read David Copperfield and The Pickwick Papers in prison, paid the novelist an admiring visit in London in 1862. Mark Twain marveled at “the complex but exquisitely adjusted machinery that could create men and women, and put the breath of life into them.”

Dickens had a large, wide-ranging circle of friends; founded and edited magazines and newspapers; traveled widely in Europe; walked ten miles or more a day through London; wrote dozens of letters every afternoon; and somehow found the time, with Baroness Angela Burdett-Coutts, one of England’s wealthiest women, to create and administer for a decade the Home for Homeless Women, a shelter for prostitutes in London’s East End.

Dickens’ domestic life, however, had become increasingly unhappy. He had fathered ten children with Catherine, micromanaged their lives and pushed all to succeed, but one by one, they fell short of his expectations. “Dickens had more energy than anyone in the world, and he expected his sons to be like him, and they couldn’t be,” Claire Tomalin tells me. The eldest, Charles, his favorite, failed in one business venture after another; other sons floundered, got into debt and, like Martin Chuzzlewit, escaped abroad, to Australia, India, Canada, often at their father’s urging.

“He had a fear that the genetic traits—the lassitude in Catherine’s family, the fecklessness and dishonesty in his own—would be [passed down to his sons],” says Tomalin.

On a clear autumn afternoon, the biographer and I stroll a muddy path beside the Thames, in Petersham, Surrey, a few miles west of London. Dickens craved escape from London into the countryside and, before he moved permanently to rural Kent in 1857, he, Catherine, their children and numerous friends—especially John Forster—vacationed in rented properties in Surrey.

Dickens also had grown alienated from his wife. “Poor Catherine and I are not made for each other, and there is no help for it,” he wrote to Forster in 1857. Shortly afterward, Dickens ordered a partition built down the center of their bedroom. Soon, the novelist would commence a discreet relationship with Ellen “Nelly” Ternan, an 18-year-old actress he had met when he produced a play in Manchester (see below). Coldly rejecting his wife of 20 years and denouncing her in the press, Dickens lost friends, angered his children and drew inward. His daughter Katey told a friend that her father “did not understand women” and that “any marriage he made would have been a failure.” In The Invisible Woman, a biography of Ternan published two decades ago, Tomalin produced persuasive evidence that Dickens and Ternan secretly had a child who died in infancy in France. The claim challenged an alternative interpretation by the Dickens biographer Peter Ackroyd, who insisted—as do some Dickensians—that the relationship remained chaste.

On my last day in England, I took the train to Higham, a village near Rochester, in North Kent, and walked a steep mile or so to Gad’s Hill Place, where Dickens spent the last dozen years of his life. The red-brick Georgian house, built in 1780 and facing a road that was, in Dickens’ time, the carriage route to London, is backed by 26 acres of rolling hills and meadows. Dickens bought the property in 1856 for £1,790 (the equivalent of about £1.5 million, or $2.4 million today) and moved here the following year, just before the end of his marriage and the ensuing scandal in London. He was immersed in writing Little Dorrit and Our Mutual Friend, rich, dense works that expose a variety of social ills and portray London as a cesspool of corruption and poverty. Dickens’ art reached new heights of satire and psychological complexity. He crammed his works with twisted characters such as Mr. Merdle of Little Dorrit, who, admired by London society until his Madoff-style Ponzi scheme collapses, commits suicide rather than face up to his disgrace, and Our Mutual Friend’s Bradley Headstone, a pauper turned schoolteacher who falls violently in love with Lizzie Hexam, develops a murderous jealousy toward her suitor and stalks him at night like an “ill-tamed wild animal.”

Gad’s Hill Place, which has housed a private school since it was sold by Dickens’ family during the 1920s, offers a well-preserved sense of Dickens’ later life. Sally Hergest, administrator for Dickens heritage programs at the property, takes me into the garden, pointing out a tunnel that led to Dickens’ reproduction Swiss chalet across the road. A gift from his friend, the actor Charles Fechter, the prefab structure was shipped from London in 96 crates and lugged uphill from Higham Station. It became his summer writing cottage. (The relocated chalet now stands on the grounds of Eastgate House in Rochester.) We continue into the main house and Dickens’ study, preserved as it was when he worked there. Propped in the hallway just outside are the tombstones from Dickens’ pet cemetery, including one for the beloved canary to whom Dickens fed a thimbleful of sherry each morning: “This is the grave of Dick, the best of birds. Died at Gad’s Hill Place, Fourteenth October 1866.”

The last years were an ordeal for Dickens. Plagued by gout, rheumatism and vascular problems, he was often in pain and unable to walk. His productivity waned. Nelly Ternan was a comforting presence at Gad’s Hill Place during this period, introduced to guests as a friend of the family. For the most part, though, she and Dickens carried on their relationship in secret locales in the London suburbs and abroad. “I think he enjoyed the false names, false addresses, like something out of his novels,” says Tomalin. “I speculate that they sat down and laughed about it, [wondering] what did the neighbors, the servants think?” Returning from a trip to Europe in June 1865, their train derailed near Staplehurst, England, killing ten passengers and injuring 40, including Ternan. Dickens was acclaimed as a hero for rescuing several passengers and ministering to the casualties, but the incident left him badly shaken.

In 1867, he left Ternan behind and embarked on his second journey to the United States—a grueling, but triumphant, reading tour. Mark Twain, who attended Dickens’ January 1868 appearance at Steinway Hall in New York, described a venerable figure “with gray beard and moustache, bald head, and with side hair brushed fiercely and tempestuously forward...his pictures are hardly handsome, and he, like everybody else, is less handsome than his pictures.” The young Regency dandy had become a prematurely old man.

Hergest leads me into the salon, with its panoramic view of Dickens’ verdant estate. “When he was here, he hosted cricket matches for the locals on the lawn,” she tells me. Today, backhoes are clearing ground for a new school building. The 18th-century manor will be converted into a Dickens heritage center open to the public. We enter the conservatory, with its soaring glass roof and replicas of the Chinese paper lanterns that Dickens was hanging here only two days before he died.

Dickens spent the morning and afternoon of June 8, 1870, in his chalet, working on The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Later that day, he was felled by a cerebral hemorrhage. He was carried to a sofa—it is preserved in the Birthplace Museum in Portsmouth—and died the following day. The author’s final moments, at age 58, come complete with a Dickensian twist: According to an alternative version of events, he collapsed during a secret rendezvous with Ternan in a suburb of London and was transported in his death throes to Gad’s Hill Place, to spare the lovers humiliation.

Millions around the world mourned his passing. Although he had professed a wish to be buried in his beloved Kentish countryside, far from the crowded, dirty city he had escaped, Dickens was entombed at Westminster Abbey. Tomalin, for one, finds it an appropriate resting place. “Dickens,” she says, “belongs to the English people.”

The conventional take has always been that the Dickens character closest to the man himself was David Copperfield, who escapes the crushing confines of the bootblacking factory. But an argument could be made that his true counterpart was Pip, the boy who leaves his home in rural England and moves to London. There, the squalor and indifference of the teeming streets, the cruelty of the girl he loves and the malice of the villains he encounters destroy his innocence and transform him into a sadder but wiser figure. In the original ending that Dickens produced for Great Expectations, Pip and Estella, long separated, meet by chance on a London street, then part ways forever. But Dickens’ friend, the politician and playwright Edward Bulwer-Lytton, urged him to devise a different, cheerful plot resolution, in which the pair marry; Dickens ultimately complied. The two endings represent the twin poles of Dickens’ persona, the realist and the optimist, the artist and the showman.

“In the end, Dickens felt [the original version] was too bitter for a public entertainer,” Newell, the film director, says in his trailer on the set. “That’s what is so extraordinary about Dickens. He has this huge instinct for literature as art, and at the same time, boy, does he bang the audience’s drum.”

Frequent contributor Joshua Hammer lives in Berlin. Photographer Stuart Conway maintains a studio near London.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)