Gorgeous Portraits of Spineless Sea Creatures

In a new book, San Francisco-based photographer Susan Middleton captures the curious gestures and expressions of marine invertebrates

"Susan, your octopus got loose again!" A crewmember delivered the news to photographer Susan Middleton late at night during a 2006 expedition in the French Frigate Shoals, the largest atoll in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

Middleton rushed to the wet lab where she had been photographing a day octopus alongside scientists collecting and listing marine invertebrates as part of the Census of Marine Life, a decade-long international collaboration (2000-2010) to assess the world's ocean inhabitants.

Middleton knew she had tucked the octopus into a five-gallon bucket with a lid before she went to bed, but it had escaped twice. On its third breakaway, Middleton found it trying to make a run for the deck, its three-foot-long arms sticking to the floor, and its talent for changing color, pattern and texture no match for the linoleum.

The portrait that Middleton eventually captured of the octopus before putting it back in the sea is one of the 250 images she photographed for her new book, Spineless: Portraits of Marine Invertebrates, The Backbone of Life, published by Abrams.

Middleton didn't pick up a camera until after she graduated from Santa Clara University with a degree in sociology, yet it was her photography that brought her to the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, where she established the institution's first photography department. In the early 1980s, the style of her plant and animal portraits took a dramatic turn when she photographed a federally endangered French toad sand lizard on a piece of black velvet instead of in a composed "natural" environment. "By removing visual distractions, I allow the viewer to concentrate on the subject with a vivid clarity that is difficult and often impossible to see in nature," she says. The technique led to an exhibition and her first book, Here Today: Vanishing Species, co-authored with David Liittschwager, her collaborator on four books. She has photographed black-footed ferrets in Wyoming, condors in California and rare plants on the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

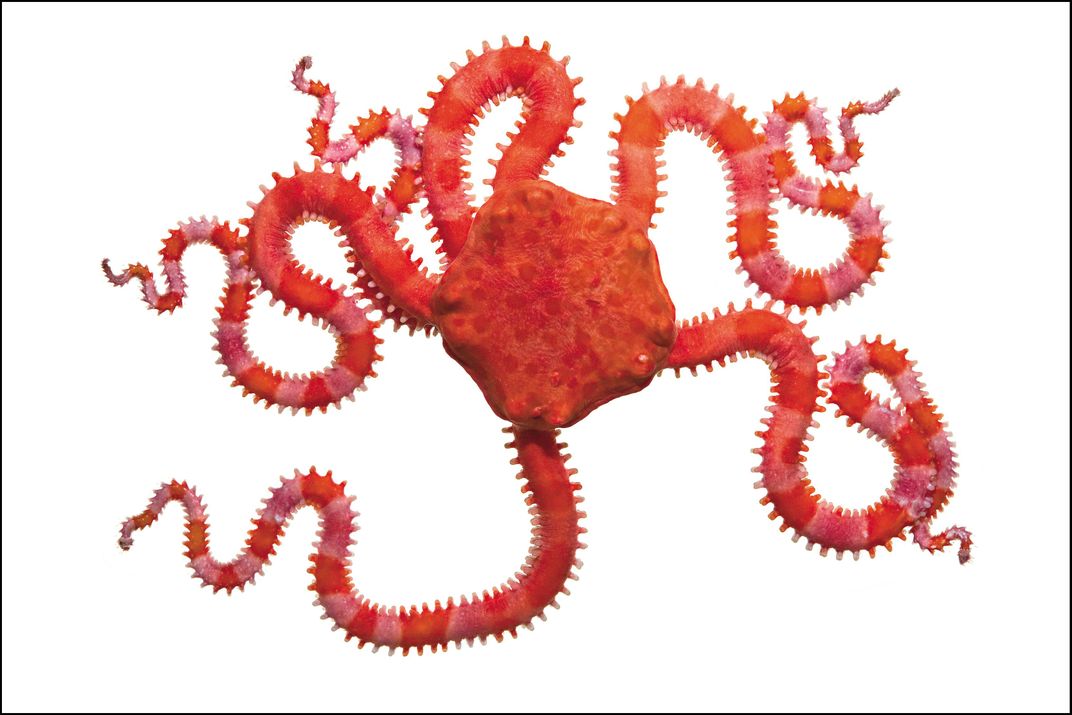

For Spineless, Middleton made jellies, crabs, octopuses, sea urchins and anemones her subjects. So little is known about almost all marine invertebrates, even though they make up 98 percent of wildlife in the ocean. "It is an under-studied, less conspicuous realm of life," she says, "and a true frontier."

The San Francisco-based photographer is drawn to the creatures’ forms, patterns, textures and colors. "As an artist I am enthralled with their foreignness; how they look different from us, and how they defy what it seems like animals should look like," she says. In the book, Middleton writes, “Colorful, quirky, quivery, spindly, spiky, sticky, stretchy, squishy, slithery, squirmy, prickly, bumpy, bubbly, and fluttery, the invertebrates appear almost surreal, even alien.”

To have access to the animals she wanted to shoot, which ranged in size from a five-millimeter-long Columbia doto sea slug to a juvenile Pacific giant octopus bound to reach 100 pounds by adulthood, Middleton joined two NOAA research vessels, the Oscar Elton Sette for the Census of Marine Life in 2006 in the French Frigate Shoals and the Hi’ialakai in 2008 for a coral reef monitoring survey through the Line Islands, a string of atolls and coral islands in the Central Pacific Ocean. The scientists on the 2006 expedition predicted that at least 100 species of the 2,500 collected would be new to science. Scientists are still analyzing many of those species, but two that Middleton photographed have been confirmed as new. One of the newly described species, the Kanaloa squat lobster (Babamunida kanaloa), is known only from the collected specimen that Middleton photographed. She calls the long-legged crustacean “the stilt walker.”

Middleton met her muse, marine biologist Gustav Paulay, on that expedition, and he suggested she work at University of Washington's Friday Harbor Marine Lab on San Juan Island, northwest of Seattle. "It's like a smorgasbord for nature photographers," said Paulay of the biologically rich area. Middleton spent parts of six summers at Friday Harbor, where she worked closely with Paulay and scientist Bernadette Holthuis, who wrote short species profiles for the book.

At Friday Harbor, Middleton borrowed creatures collected by the scientists and placed them in her glass studio tank, measuring 9 inches wide, 12 inches tall and 4 inches deep. The tank sat on a draped white cloth that served as a backdrop. The setup is the basis for a technique that has evolved over 30 years. Middleton is fast with her camera, a Canon EOS 1DS Mark 3 that she attaches to a tripod. The camera and a flash that she positions with her left hand are synchronized. She works alone and observes the animals for a long time, looking for a striking gesture or expression, before snapping the shutter. "My subjects tell me what to do. I just have to be ready," she says.

In the seven years she worked with live animals for Spineless, she felt like she witnessed many curious behaviors. When Paulay gave her a rare giant flatworm to photograph, Middleton was certain that the brown blob the size of her palm would not make the cut. "It didn't have beautiful colors or graphic design elements," she says. She took some "brown blob pictures" and wasn't at all impressed until the creature began to dance. "It became a contortionist and made all these amazing sculptural gestures. It could stand up on one little edge, curl itself around and turn itself inside out," says Middleton. She summoned Paulay who admitted he didn't know a flatworm could make those moves.

"Susan is an ambassador," says Paulay. "As people spend more and more time away from nature, visuals are a way to get them to experience it. Her portraits are a great way to introduce people to the diversity of life on Earth."

Middleton has spent her career drawing attention to animals affected by human action. She introduced us to North American endangered species that were about to blink out; she artfully arranged and photographed the undigested plastic found in an autopsied albatross; and now she's showing us a little-known realm of life that is being impacted by ocean acidification—many marine invertebrates have shells made of calcium carbonate that could dissolve in more acidic waters.

In her photos, a white phantom crab looks dapper, a gold-banded hermit crab struts as if on a catwalk and an octopus looks to be in Victorian dress with its lacy tentacles and Gustav Klimt-like patterns.

"We get carried away with ourselves and other animals with spines," says Middleton. "And yet, it's an invertebrate world. They are the original protagonists."