Grand Reopening: Speaking of Art

Two museums return home and invite visitors to engage in “conversations”

Most art museums seek to dazzle like Ali Baba's cave, but the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) and the National Portrait Gallery (NPG), which jointly reopen in the old Patent Office Building on July 1 after a six-year, $283 million renovation, greet visitors with a homey embrace. Touring the collections is like riffling through a family album or climbing into an attic rich with heirlooms. "One of the key things for me was striking the right balance between knowledge and experience," says SAAM director Elizabeth Broun. "There are certain people who are right at home in an art museum and others who might be intimidated."

Says Eleanor Harvey, SAAM's chief curator: "We spent a lot of time trying to figure out why people are scared of art. How do you give people back the sense of exploration and wonder?" The answer: tell them a story. "People love stories," Harvey continues. "We decided to let the art tell stories about how we got to be the country we are today, so art is not a tangent to your life but an illumination.

Broun and Harvey's colleagues at the National Portrait Gallery came to much the same conclusion. Although the NPG is a newer museum, it was born prematurely gray; at its opening in 1968, it specialized in presidents and generals— "white men on horses," quips the museum's director, Marc Pachter. Over the following decades the NPG broadened its range and, in 2001, scrapped its requirement that portrait subjects be dead for at least ten years. "We had a joke about whether someone was dead enough," Pachter says. The decade-dead rule was intended to ensure historical perspective, but it worked against the museum's ability to connect to its audience. "We have expanded, along with the nation, our notion of the background and definition of greatness," Pachter adds. "What we have not abandoned is the notion that it is still important to think about greatness. Mediocrity is well represented elsewhere."

Through portraits of remarkable Americans, whether revered (George Washington) or notorious (Al Capone), the NPG attempts to explore the ways in which individuals determine national identity. "Our society is obsessed by the role of the individual," Pachter says, "from celebrity culture today to heroes of the past." By displaying art in thematic groupings, both the NPG and SAAM aim to provoke conversations about what it means to be an American.

The two museums share one of the most august spaces in the nation's capital—the neo-Classical Patent Office Building, which was built, starting in 1836, to showcase the ingenuity of inventors. Over the years, the glories of its architecture had been dulled by alterations made to satisfy demands of the moment; the closing of the museums in January 2000 permitted a renovation that has stripped these away. Administrative offices were banished to create new galleries that fill the three main floors. Hundreds of walled-up windows are now exposed, allowing light once again to flood the interior. The windows were refitted with new glass, which was handblown in Poland to reproduce the slight waviness of the originals and, in a nod to 21st-century technology, augmented with filters that screen out ultraviolet rays that can damage works of art. "People will be amazed that the building that looked like a dark cave is now probably the most beautifully lit building in the city," says Broun.

No longer reached through separate doorways, the two museums will welcome visitors through a grandly porticoed entrance on the building's south facade. But while visitors to the two museums may arrive together, the museums themselves came here by divergent paths. SAAM traces its origins back to a 19th-century collection of mainly European art put together by a civic-minded art enthusiast named John Varden. At first, Varden displayed these works to the public in a gallery attached to his home, but by 1841 he had moved them to the top floor of the newly opened Patent Office Building. Willed to the nation, the Varden holdings were transferred to the first Smithsonian Institution building, the Castle, in 1858, from which the ever-growing collection relocated to the Arts and Industries Building in 1906 and to the new Natural History Building four years later. Then, in 1958, Congress presented the Patent Office Building to the Smithsonian. In 1962, the Institution made the decision to divide the building's space between its art collection, vastly expanded from the original Varden bequest, and the National Portrait Gallery, which Congress created that same year.

Over the years SAAM—once called the National Collection of Fine Arts—has narrowed its mission to focus on American art, amassing one of the world's largest collections. The depth of the holdings allows the curators to present a nuanced narrative that can provoke a response from the viewer. "At the National Gallery and the Met," Harvey says, "what you see is an array of masterworks—gems in the tiara. Sometimes what you need to tell a complete story is more of a matrix of events and ideas that puts these masterworks in context. At SAAM, we're all about conversations."

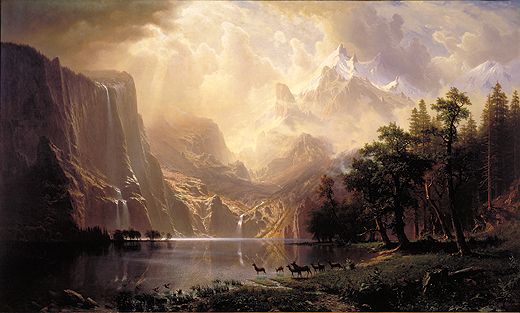

And how best to start a conversation? In their new installations, SAAM curators chose to begin with landscapes. "One of the first things people usually ask in this country is 'Where are you from?' and the idea is that that information tells you something," Harvey explains. "We wanted to show how the physicality of America, from Niagara Falls to the Sierra Nevada, inflected how we developed as a country and a culture." Visitors who turn left at the main entrance to go to SAAM will be greeted by such Hudson River School paintings as Asher B. Durand's Dover Plain, Dutchess County, New York and by the even more expansive grandeur of the American West, as in Victor Higgins' Mountain Forms #2. The curators hope the landscapes will encourage visitors to think about broader issues—such as land development and conservation. But Broun emphasizes that SAAM is not a textbook. "It's 'What are the consistently relevant questions in every period?'" she says. "It's more about experience and insight than information." In this introductory exhibition, the curators have also hung a large group of the photographs of public monuments that Lee Friedlander has been taking since the 1960s. That series segues into another photographic display, in which Americans of all ages and colors are represented in the works of many photographers. Says Harvey: "There are photographs of a Fourth of July barbecue, Lewis Hine’s tenement kids, mid-century debutantes—to remind you that photography occupies a vernacular role, and without people, place doesn’t mean anything."

After entering, those who turn right, toward the National Portrait Gallery, will also find themselves in a familiar, contemporary environment. In two exhibitions, "Americans Now" and "Portraiture Now," visitors "will be able to see portraits of people just like them and go into the historical galleries with that visual information to start a dialogue about historical lives," says Brandon Fortune, the NPG's associate curator of painting and sculpture. "You can't get to Benjamin Franklin without walking past big photographs of teenagers. We're very proud of that." In addition to photography, which the NPG began collecting in 1976, the museum has embraced such unconventional approaches to portraiture as a hologram of President Reagan and a video triptych of David Letterman, Jay Leno and Conan O'Brien. "These are all delivery systems of personality," says Pachter. "I think of coming to the gallery as an encounter between lives. You're not coming just to look at brushstrokes."

In a kind of operatic overture—in galleries labeled "American Origins"—the NPG sweeps across the centuries from 1600 to 1900 on the first floor, before arriving, on the second, at the exhibition that most pre-renovation visitors will likely remember best: "America's Presidents." In the previous installation, the collection was confined to the Hall of Presidents, but that imposing, stone-columned space now covers only the nation's leaders from Washington to Lincoln, and a gallery about twice its size brings the story up to the present, including an official portrait, William Jefferson Clinton by Nelson Shanks, that was unveiled on April 24.

The prize of the presidential collection—arguably, of the entire NPG—is the full-length painting of Washington by Gilbert Stuart known as the Lansdowne portrait. Stuart painted it from life in 1796, shortly before the first president concluded his second term in office. Although two other versions exist, this is the original. It depicts Washington in a simple black suit, clasping a sheathed ceremonial sword in his left hand and extending his right arm in what may be a gesture of farewell. "The Constitution barely describes the presidency," Pachter says. "This painting is the defining document." Ironically, the Lansdowne portrait spent most of its life in England. It was commissioned by a wealthy Pennsylvania couple, the Binghams, as a gift for the Marquis of Lansdowne, who had been sympathetic to the American cause. In the 19th century, the painting was sold to the Earl of Rosebery, from whom it descended into the possession of Lord Dalmeny, the current heir to the earldom.

From the time the NPG first opened, the museum had exhibited the Lansdowne portrait on extended loan.When Dalmeny announced his intention of selling it at auction in 2001, Pachter was aghast. "It is a great painter doing a portrait of a great American at the perfect moment," he says. "That is our ideal image. Losing it was the most awful thing I could have contemplated." He went to Dalmeny, who offered it to the Smithsonian for $20 million—"a lot of money," Pachter admits, "but maybe less than he would have gotten at auction." Pachter took to the radio and television airwaves to publicize the museum's plight and, after just nine days, found deliverance in a benefactor. The Donald W. Reynolds Foundation of Las Vegas, Nevada—a national philanthropic organization founded in 1954 by the late media entrepreneur for which it was named—donated the full purchase price, plus an additional $10 million to renovate the Hall of Presidents and to take the Lansdowne painting on a national tour. Last October, the foundation donated an additional $45 million for the overall work on the Patent Office Building. "It was," says Pachter, "to use one of George Washington's words, 'providential.'"

While SAAM hasn't reeled in quite as big a fish as the Lansdowne, it, too, made some splashy acquisitions during the renovation, including Industrial Cottage, a 15-foot-long Pop Art painting by James Rosenquist; The Bronco Buster, a Frederic Remington bronze sculpture; and Woman Eating, a Duane Hanson resin and fiberglass sculpture. SAAM has also commissioned a new work, MVSEVM, by San Francisco artist David Beck, a treasure cabinet with pull-out drawers that is inspired by the neo-Classical grandeur of the Patent Office Building.

While the transformation of offices into galleries opened up 57,000 square feet of additional floor area, the reclamation of windows in the building resulted in a loss of wall space, which SAAM curators have seized as an opportunity to display more sculpture. "We've got the largest collection of American sculpture, period," says SAAM's Harvey. "It's not a footnote, an afterthought, an appendage. It's part of the story of American art." In the old days, SAAM displayed most of its sculpture in the building's long corridors. Now sculpture is dispersed throughout the galleries.

So is furniture, which was not previously exhibited in the museum. "It's not about becoming Winterthur [the du Pont estate near Wilmington, Delaware]," says Harvey. "In Colonial history, with the exception of John Singleton Copley and a couple of other painters, you're better off with furniture.

By the time a visitor reaches SAAM's contemporary collection on the third floor, the distinctions between fine and decorative art begin to blur. A 22-foot painting by David Hockney of interlocking abstract forms, illuminated by a programmed series of colored lights, shares space with the late video artist Nam June Paik's neon-festooned assemblage of television sets in the shape of a map of the United States. "We focused a lot on contemporary artworks that we feel are deeply experiential," says director Broun. In addition, the definition of what constitutes an American artist is interpreted broadly. The NPG depicts non-American citizens who have influenced American history—Winston Churchill and the Beatles, for example—and SAAM includes foreign artists, such as British-born David Hockney, who had an important impact on American culture. "Hockney has been in Los Angeles since the 1970s," says Harvey, "and there is no L.A. art of the 1980s without him."

Like most major museums, SAAM will never have enough space to display the bulk of its treasures. To help remedy that, the renovation features an innovative storage and study center that contains some 3,300 works (more than three times the number in the exhibition galleries) and is fully accessible to visitors. Paintings, sculptures, crafts and miniatures can all be scrutinized in 64 glass cases on the third and fourth floors, with interactive kiosks to provide information on individual pieces.

Besides expanding the viewable collection, the Luce Foundation Center for American Art, as the storage and study center is known, aims to enhance the visitor's appreciation of the curator's role. "We have 41,000 artworks," says Broun. "Any other team of people would have picked different ones to show in the galleries. It's a way of empowering the public to see not only what you choose but what you didn't choose." In the same spirit, NPG curators are also emphasizing that museum displays depend on the preferences and selections of the particular person assembling them. Each year, for example, one gallery will be given over to an individual curator's take on an individual life: for the opening installation, poet and NPG historian David Ward has created an exhibit on Walt Whitman, who nursed wounded soldiers in the Patent Office Building during the Civil War. "I want people to understand that these lives are seen through different mirrors," says Pachter. "It might be the artist's, it might be the curator's, but these are representations, not the life itself."

Perhaps the most unusual feature of the reconfigured building is the Lunder Conservation Center, on the third-floor mezzanine and the skylit fourth-floor penthouse. In the center, which is shared by SAAM and the NPG, museumgoers can watch through glass walls as conservators analyze and, very carefully, restore artworks. "I think people are genuinely fascinated by what goes on behind the scenes at a museum," Harvey says. "This gives them a window on it, literally."

Another attempt at breaking down the barriers between the public and art is a national portrait competition that the NPG inaugurated last year. Named after a longtime volunteer docent who underwrote it, the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition attracted more than 4,000 contestants, from every state, in its first year. The winner, to be announced shortly before the museum opens, will receive $25,000 and a commission to portray a prominent American.

Both museums feature works by artists who never became household names. Indeed, at SAAM, there are a number of distinguished pieces by self-taught amateurs. "Art is something you make out of passion and a desire to communicate," says Harvey. "I think it's a sad day when you stop making refrigerator art. You keep on singing in the shower. You shouldn't stop making art." Probably the most popular work in SAAM is by a man who followed that credo with religious zeal. The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations' Millennium General Assembly is an eye-popping construction of furniture, light bulbs and other discards that Washington, D.C. janitor James Hampton wrapped in tinfoil and assembled unobserved in a rented garage, beginning around 1950. Discovered only after Hampton's death in 1964, this glittering creation could be the suite of furniture of a heavenly host in a low-rent tinsel paradise.

In representing the fierce, isolated individuality of one artist's vision, Hampton's Throne is a fitting complement to a gallery devoted to eight works by Albert Pinkham Ryder. "Ryder is almost emblematic for our building," says Broun. "This building was looking back to a classic era and also looking to the future, and so was Ryder. He was painting narrative stories from the Bible and 16th-century English history. At the same time, he was working with new types of paint and exploring ways that the paint itself conveys the meaning of the picture—so that if you work long enough with layer on boggy layer, you get a meaning that you wouldn’t expect." Because Ryder experimented restlessly with new ways to bind his pigments, many of his paintings have darkened with time and their layers have cracked. Nevertheless, he was a prophetic figure for later generations of painters. Visionary, recklessly inventive, leading a life both noble and tragic, he was also peculiarly American. For a visitor wandering the reborn Patent Office Building galleries, the Ryder room is a fine place to pause and contemplate the mysteries of our national identity.

Arthur Lubow wrote about Norwegian artist Edvard Munch in the March issue of Smithsonian. Timothy Bell lives in New York City and specializes in architectural photography.