A Preview of Grant Wood’s New Retrospective at the Whitney

The artist who posed as a farmer gets the star treatment at the New York museum in his biggest show ever

:focal(2770x1633:2771x1634)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/c7/49c763b0-5276-4ea2-ba55-dd6e87f5a02a/mar2018_j13_grantwood.jpg)

Countless parodies have propelled Grant Wood’s American Gothic into pop iconography, yet the artist, far from a one-hit wonder, remains strangely obscure. “He’s undervalued and under known,” says Barbara Haskell, curator of “Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables,” opening in March at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. It’s the most comprehensive exhibition of the artist ever, and includes more than 40 paintings; Arts and Crafts objects (a corncob chandelier, a chair, a textile design); book covers; a half-scale replica of his stained-glass window for Cedar Rapids’ Veterans Memorial Building; and murals such as the triptych The First Three Degrees of Freemasonry, which has never before left Iowa.

The timing is propitious, Haskell says, sitting in her office where tall poster boards pinned with exhibition images lean against the walls. “In the ’20s the fascination in the popular culture was about glamour, urban life—think about the flappers, Fitzgerald. And the Midwest had begun to be derided as provincial, unsophisticated, uneducated.” Then came the stock market crash in 1929, and “community, hard work and self-reliance began to be seen as the essence of American character. The Midwest came into being as kind of the real America. The whole idea about what it means to be American—the attack against elitism, the pull between rural and urban—we’re in the same period right now.”

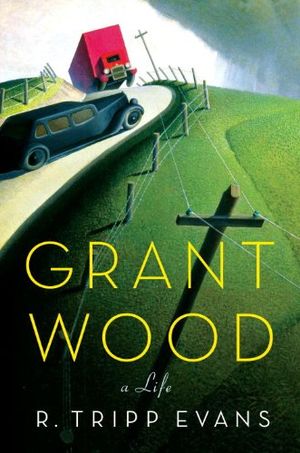

Grant Wood: A Life

He claimed to be “the plainest kind of fellow you can find. There isn’t a single thing I’ve done, or experienced,” said Grant Wood, “that’s been even the least bit exciting.”

What elevates Wood’s art above that of his Regionalist peers—Wood, Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry were christened the “Midwest Triumvirate”—is an infusion of his anxieties. “There’s a psychological undertow to his best works,” says R. Tripp Evans, author of Grant Wood: A Life. “It’s a kind of love for, but questioning of, his country. And if you look at his work more closely you see his struggles as an Iowan, as a closeted gay man, as someone who’s harnessed to a chauvinistic movement that served as protection for him but was a trap for him as well.”

In a way, the artist’s greatest creation was his persona. “All the good ideas I’ve ever had came to me while I was milking a cow,” Wood famously said. He never milked a cow. He was an intellectual who came across as anti-intellectual, a liberal assumed to be a conservative, a man who loved theatricals and costume parties (a favorite role was Cupid) but lived in bib overalls. “The overalls were a kind of idealized version of what he believed his father wanted him to be,” Evans says. “It really was a form of farmer drag—it was a costume he wore every day.”

Haskell, opening a coffee-table book and turning to Wood’s landscapes, points out that many are populated with toylike houses and cars, and she mentions that Wood’s father died when the boy was just 10 years old. The scenes “are bucolic and harmonious,” she says, but “there’s an airless, frozen quality and a kind of chilly make-believe. It’s as if he was occupying two worlds—what he imagined was his memory, this idealized world, and his real life. There’s an eerie silence and solitude—alienation. You feel the tension that he felt in his life.”

Evans agrees. “Curry looks dated now. Benton seems very much of his period. You just don’t get that sense of dread and unease you get when Wood is at his best. Wood, in his kind of freakiness, continues to fascinate us.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.