Guys and Molls

Bold, garish and steamy cover images from popular pulp-fiction magazines of the 1930s and ‘40s have made their way from newsstands to museum walls

A blonde in a red strapless gown grasps the receiver of an emergency telephone, but her call to the cops has been interrupted. From behind her, a beefy brute with a scar on his cheek clamps a meaty hand over her mouth. His other hand presses a .45-caliber automatic against her neck.

What will become of the blonde beauty? Can the police trace her call in time? And what’s a dame doing out alone at night in a red strapless dress anyway? Newsstand passersby who saw this scene—painted by New York artist Rafael de Soto for the July 1946 cover of a pulp-fiction monthly called New Detective Magazine—could pick up a copy for pocket change and satisfy their curiosity in a story inside titled “She’s Too Dead for Me!”

Pulp-fiction magazines—or the pulps, as everyone called them—were monthly or biweekly collections of stories printed on the cheapest wood-pulp paper that could be run through a press without ripping. Their covers, however, were reproduced in color on more expensive coated stock because the gripping, often steamy artwork sold the magazines.

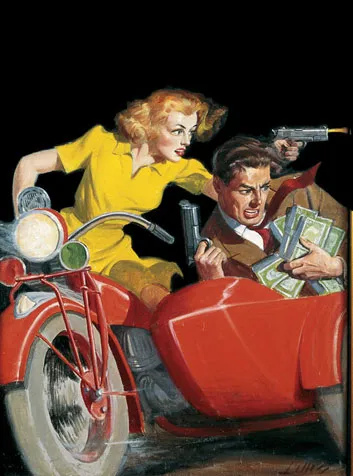

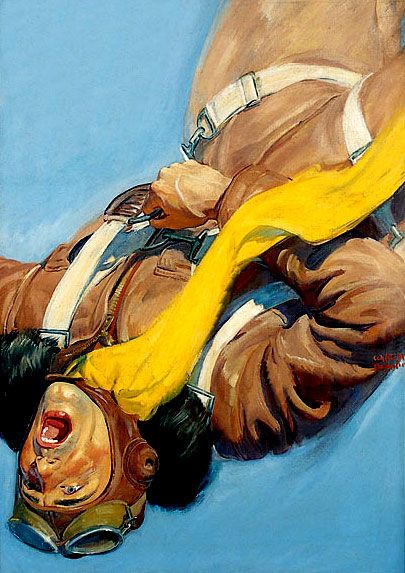

A good pulp cover told a story in a flash. Ahandsome flyboy hurtles through the air upside down, his mouth open in a scream, his fist clutching the ring of his parachute’s rip cord. Disembodied eyes stare at a furtive man in a pulleddown fedora as he pauses under a streetlight; his hands grip a newspaper with the bloodred headline “BODY FOUND.”

“The artists who painted these covers had to catch your eye in the depths of the Depression and make you reach for that last ten cents in your pocket,” says pulp-art collector Robert Lesser, referring to the usual cover price. “Bear in mind, a dime was real money back then. For a nickel, you could ride a subway or buy a large hot dog with sauerkraut.”

Lesser, 70, a New York City playwright and retired advertising- sign salesman, bought his first original pulp-cover painting in 1972. It was a riveting 1933 portrayal by artist George Rozen of radio and pulp-fiction staple the Shadow (p. 54). Cloaked in black against a vibrant yellow background, the “master of the night” is pictured clawing his way out of a captor’s net. Over the next 30 years, Lesser tracked down and acquired many more pulp paintings—some 160 in all. Through the end of August, visitors to the Brooklyn Museum of Art can see 125 of these works in an entertaining new exhibition, “Pulp Art: Vamps, Villains, and Victors from the Robert Lesser Collection.”

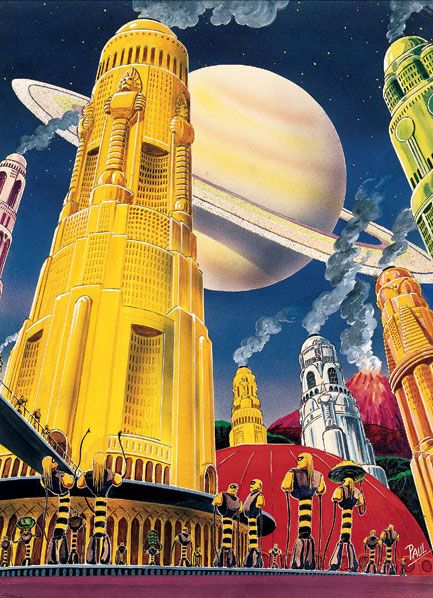

Descendants of the Victorian penny dreadfuls, the pulps enjoyed their heyday in the 1930s and ’40s. Their fans (mostly men) plunked down more than a million dollars a month in small change to follow the adventures of Doc Savage, the Shadow, the Mysterious Wu Fang, G-8 and His Battle Aces, or Captain Satan, King of Detectives. There were sciencefiction pulps, crime pulps, aerial-combat pulps, Westerns, jungle adventures and more. Americans were eager for cheap escapist entertainment during the Depression and the war years that followed, and the pulps delivered.

“My dad would buy a pulp magazine,” Lesser says, “and my sister and I would know to leave him alone. He’d joined the French Foreign Legion for the next few hours.”

Best-selling authors like Edgar Rice Burroughs, Zane Grey, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Erle Stanley Gardner and even 17-year-old Tennessee Williams got their start writing for pulp publishers clustered in midtown Manhattan. But literary writers were far outnumbered by fasttyping hacks who pounded out stories like “Blood on My Doorstep,” “Gunsmoke Gulch,” “Z is for Zombie” and “Huntress of the Hell-Pack” for a penny or less a word.

If the pay scale was any indication, pulp publishers valued painters more than writers. Pulp artists typically earned $50 to $100 for their 20-by-30-inch cover paintings, which they might finish in a day. Atop painter could get $300.

“Sometimes the publishers wanted a particular scene on a cover,” says Ernest Chiriacka, 90, who painted hundreds of covers for Dime Western Magazine and other pulps in the 1940s. “But otherwise they just wanted something exciting or lurid or bloody that would attract attention.” Publishers might even hand their writers an artist’s sketch and tell them to cook up a story to go with it. Like other ambitious painters, Chiriacka viewed pulp art as a way to pay his bills and simultaneously hone his craft. Eventually, he landed higher-paying work for “the slicks,” glossy family magazines like Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post. “The pulps were at the very bottom of the business,” he says. He signed his pulp paintings “E.C.,” if at all. “I was ashamed of them,” he confesses.

“Chiriacka’s attitude was typical,” says Anne Pasternak, guest curator of the Brooklyn exhibition. “The artists, many of whom were trained in the finest art schools in the country, considered this a lowbrow activity. Nonetheless, their job was to make the most startling images they possibly could because there were so many pulp titles on the newsstand, and the competition was tough.”

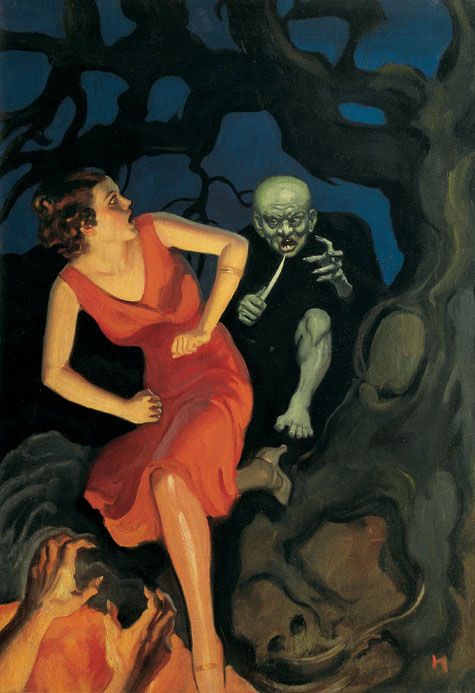

Big-name artists like N. C. Wyeth and J. C. Leyendecker occasionally stooped to paint for the pulps, but most pulp artists were anonymous. The best of them managed to make names for themselves within this specialized world: sciencefiction painters Frank R. Paul and Hannes Bok; depicters of gangsters and victims in extremis like Norman Saunders and Rafael de Soto; fantasy-adventure artist Virgil Finlay; and a man admired by his fellow pulp artists as the “Dean of Weird Menace Art,” John Newton Howitt.

A successful pulp artist mixed vivid imagination and masterful technique to create images about as subtle as a gunshot. Brushstrokes were bold, colors raw and saturated, lighting harsh, backgrounds dark and ominous. In the foreground, often in tight close-up, two or three characters were frozen in mid-struggle, their anguished or shrieking faces highlighted in garish shades of blue, red, yellow or green. Pulp art, the late cover artist Tom Lovell told an interviewer in 1996, was “a highly colored circus in which everything was pushed to the nth degree.”

An all-too-common ingredient in the storytelling formula was a stereotypical villain, whether a demented scientist with bad teeth and thick glasses or a snarling Asian crime lord in a pigtail presiding over a torture chamber. The best covers were “painted nightmares,” says Lesser, who still enjoys horror films, good and bad. He’s unenthusiastic about the content of most traditional art. “You see a landscape, a pretty woman, a bowl of fruit,” he says. Decorative stuff, in his view. “Compared to that, pulp art is hard whiskey.”

The hardest-hitting covers (and the highest-paying for the artists who made them) were the Spicies: Spicy Detective, Spicy Mystery, Spicy Western Stories, and so on. Published by a New York City outfit that blithely called itself Culture Productions, the Spicies blurred the line between mainstream fun and sadistic voyeurism. When New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia passed a newsstand in April 1942 and spotted a Spicy Mystery cover that featured a woman in a torn dress tied up in a meat locker and menaced by a butcher, he was incensed. La Guardia, who was a fan of comic strips, declared: “No more damn Spicy pulps in this city.” Thereafter, Spicies could be sold in New York only with their covers torn off. Even then, they were kept behind the counter. By the 1950s, the pulps were on their way out, supplanted by paperback novels, comic books and, of course, television.

Few people then imagined original pulp art was worth keeping, let alone exhibiting. Once a cover painting was photographed by the printer, it was put in storage or, more likely, thrown out. The artists themselves rarely saved their work. When Condé Nast bought former pulp publisher Street & Smith in 1961, the new owners put a trove of original pulp paintings (including, it seems, some unsigned works by N. C. Wyeth) out on Madison Avenue with the trash.

“This is a genre of American representational art that has been almost completely destroyed,” says Lesser. “Out of 50,000 or 60,000 cover paintings, there are only about 700 today that I can account for.” If pulp paintings hadn’t been so inherently offensive, they might have fared better. “But people didn’t want their mother-in-law to see one of these paintings hanging over their new living room sofa,” Lesser says. “This is objectionable art. It’s racist, sexist and politically incorrect.” But since he has neither a sofa nor a mother-in-law, Lesser has crammed his own two-room apartment to impassability with pulp paintings, along with toy robots and monster-movie figures. Pulp art’s scarcity, of course, is part of what makes it so collectible today. An original cover painting by Frank R. Paul or Virgil Finlay, for instance, can fetch $70,000 or more at auction.

Lesser is the proud owner of the woman-in-a-meat-locker painting by H. J. Ward that so infuriated Mayor La Guardia. Although it’s included in the Brooklyn exhibition, the museum isn’t expecting any public outcry, says Kevin Stayton, the BrooklynMuseum’s curator of decorative arts.

“Although this art may have pushed the edge of what was acceptable, it’s fairly tame by today’s standards,” Stayton explains. “Things that were troubling to the public 60 years ago, like scantily clad women, don’t really bother us anymore, while things that didn’t raise an eyebrow then, like the stereotyping of Asians as evil, cause us tremendous discomfort now.”

Contemporary British figurative artist Lucian Freud once wrote, “What do I ask of a painting? I ask it to astonish, disturb, seduce, convince.” For those with similar demands, pulp art delivers a satisfying kick. People can debate the aesthetic merits of these overwrought, disquieting, sometimes gruesome works of art, but no one can dispute their creators’ mastery of the paintbrush as a blunt instrument.