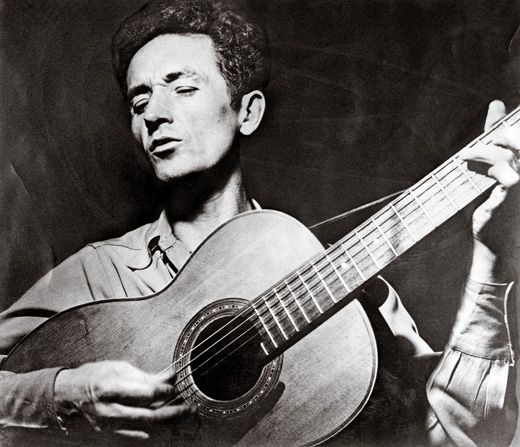

Happy 100th Birthday, Woody Guthrie!

New songs by the American folk legend keep turning up, a century after his birth

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-Woody-Guthrie-631.jpg)

The recording is old but the voice is timeless: Woody Guthrie is singing to his daughter Cathy Ann (“Stacky” to her dad) on her fourth birthday:

You’ve played, little Stacky, all day

With dolls and wagons and clay

Your bath was warm and your jammers are nice

Goodnight, little Stacky, goodnight.

It’s not clear whether Cathy ever heard the 1947 ditty; shortly after its recording, a spark from a badly wired radio ignited her crinoline birthday dress and she burned to death.

Guthrie never recovered from the loss. His sadness, friends believed, hastened the progress of his Huntington’s disease. By 1952, the folk singer couldn’t remember the words to “This Land Is Your Land,” his most famous song; soon he was hospitalized for good. (He died in 1967, at age 55.) Most of his best work was crammed into a single decade, but he is still celebrated as one of the country’s most prolific artists, the prototypical singer-songwriter and a lodestar for Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and John Lennon.

“Guthrie was one of these solar flares who pass through periodically,” says Smithsonian Folkways producer Jeff Place, who, with Robert Santelli, put together Woody at 100, a collection of songs (including his lullaby to Cathy, previously unreleased), essays and drawings in honor of the centennial of Guthrie’s birth this July 14. “He threw sparks wherever he went.”

Cathy’s death was not the only time fire touched the singer’s life. His beloved older sister Clara died in a house fire; his father was badly injured in another blaze, and Guthrie, as his illness destroyed cells in his brain, would burn his arm and lose his ability to play guitar.

“Pete Seeger said that fire was Woody’s muse,” says Guthrie’s daughter Nora. “It just followed him around.” Indeed, Guthrie’s whole existence had a combustible quality: He drank hard, couldn’t hold jobs, married three times and fathered eight children (of whom Arlo Guthrie is the eldest son), sweeping through one city after another.

Sometimes called the Dust Bowl Balladeer, Guthrie got his start performing in the late 1930s when he traveled west from his home base in dust-drowned Pampa, Texas, with displaced Arkies and Okies. In California he wrote of his fellow migrants, setting the lyrics to traditional folk tunes. By 1940 he’d moved “from California, to the New York Island,” as his song goes, befriending Lead Belly and other famous artists. His country charm and writing chops inspired the city musicians: “Next thing you know everybody’s got a guitar and harmonica rack,” Place says.

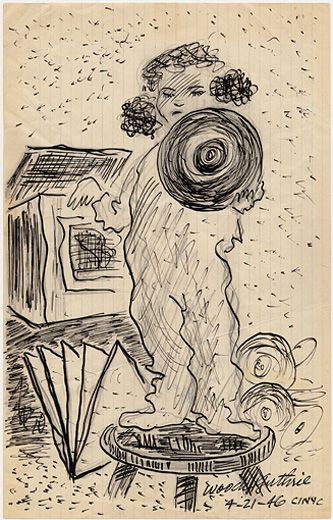

The working man’s struggle was Guthrie’s favorite subject, but he also sang of spaceships, washing dishes, one-legged sailors, Ingrid Bergman and Hanukkah. He composed a remarkable series on the builders of the Grand Coulee Dam, another (commissioned by the Army) on venereal disease and several albums of children’s music. His creativity was almost unnerving in its intensity: He sometimes delivered six songs in a sitting, or reams of skillful pen-and-ink drawings. (Many of those featured in Woody at 100 were drawn in the same week.) He also wrote several books and composed personal letters that could ramble on for 70 pages, scribbling on wrapping paper if nothing else was at hand. “Every letter would have a lyric in it,” says Nora Guthrie. “Even his journal had this flow.”

Today “This Land Is Your Land” echoes at presidents’ inaugural concerts and Occupy Wall Street rallies alike. But it’s not just the classics that survive: In 2005, the punk band Dropkick Murphys released “I’m Shipping Up to Boston,” an obscure Guthrie snippet that has since become an oft-blasted Boston Red Sox anthem.

Because Guthrie wrote so much, stashes of recordings and drawings are still being found. And it wasn’t until decades after his death that Place finally traced the origins of the “This Land Is Your Land” melody. It’s likely based on a church hymn titled “When This World’s on Fire.”