Harlem Transformed: the Photos of Camilo José Vergara

For decades, the photographer has documented the physical and cultural changes in Harlem and other American urban communities

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Girls-Barbies-Harlem-1970-631.jpg)

The year is 1990. In the foreground, a man dressed in a blue work shirt and denim overalls poses amid corn and vegetables planted on a patch of junkyard between West 118th and 119th Streets and Frederick Douglass Boulevard in Manhattan. A makeshift scarecrow, also in overalls, stands beside him. The man’s name is Eddie, he’s originally from Selma, Alabama, and he’s now an urban farmer. Welcome to Harlem.

But the story doesn’t end there. The photographer, Camilo José Vergara, has returned to the same location year after year to shoot more pictures. In 2008, he aimed his camera here and found, not a vegetable patch, but a crisply modern luxury apartment building. “On the exact spot where Eddie was standing, there’s a Starbucks today,” Vergara says. Welcome to the new Harlem.

For much of the past 40 years, Vergara has systematically shot thousands of pictures at some 600 locations in Harlem. His images cumulatively document the myriad transformations—both dramatic and subtle—in the physical, social and economic life of the community. The project helped earn him a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant in 2002.

Harlem has not been Vergara’s only focus. He has shot extensively in distressed areas of Camden, New Jersey, and Richmond, California, as well as in Detroit, Los Angeles and more than a dozen other cities. More than 1700 of his photographs are housed on a labyrinthine interactive Web site called Invincible Cities, which he hopes to develop into what he calls “The Visual Encyclopedia of the American Ghetto.” A modest yet powerful selection of his New York City work is featured in an exhibition, Harlem 1970–2009: Photographs by Camilo José Vergara, on display at the New-York Historical Society through July 9.

Harlem has long fascinated photographers. Henri Cartier-Bresson found it a rich source of the “decisive moments” he felt were the heart of the medium. Helen Levitt and Aaron Siskind found drama and beauty in Harlem’s people and surroundings; Roy DeCarava found poetry and power.

Vergara’s project is deliberately more prosaic. Rather than trying to create the perfect, captivating photograph, he piles image upon image, narrating a suite of interconnected stories with a form of time-lapse photography that spans decades.

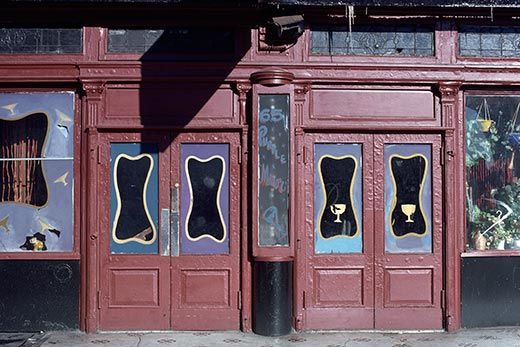

There’s a vivid example of Vergara’s method in the Harlem exhibition, documenting the evolution—or more accurately, devolution—of a single storefront at 65 East 125th Street. A series of eight pictures (or 24, on Vergara’s web site) tracks the establishment’s progression from jaunty nightclub to discount variety store to grocery/smoke shop to Sleepy’s mattress outlet and finally, to gated, empty store with a forlorn “For Rent” sign.

“This is not a photography show in the traditional sense,” Vergara says during a stroll through the New-York Historical Society gallery. “I’m really interested in issues, what replaces what, what’s the thrust of things. Photographers don’t usually get at that—they want to show you one frozen image that you find amazing. For me, the more pictures the better.”

Vergara’s work has gradually earned him a formidable reputation. In addition to his MacArthur award and other honors, he has received two grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities; his photographs of storefront churches will be exhibited at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., from June 20 to November 29; he contributes regularly to Slate.com; and his eighth book, Harlem: The Unmaking of a Ghetto, is due from the University of Chicago Press in 2010.

For all that, Vergara grumbles, he has not earned acceptance in the world of photography. His NEH grants were in the architecture category; his applications for Guggenheim Foundation grants in photography have been rejected 20 times. “If I went to the Museum of Modern Art with my pictures, they wouldn’t even look at them,” he says. “If I go to the galleries, they say your stuff doesn’t belong here.”

The problem, he feels, is that art has become all about mystification. “If artists keep things unsaid, untold, then you focus on the formal qualities of the picture, and then it becomes a work of art. The more you explain, the less it is a work of art, and people pay you less for the photograph,” he says. “But I don’t like to mystify things—I like to explain things.”

“My project is not about photography; it’s about Harlem,” he insists. “I think there is a reality out there, that if you frame it, you get at it. You may not get the whole thing, but you do get it in important ways.”

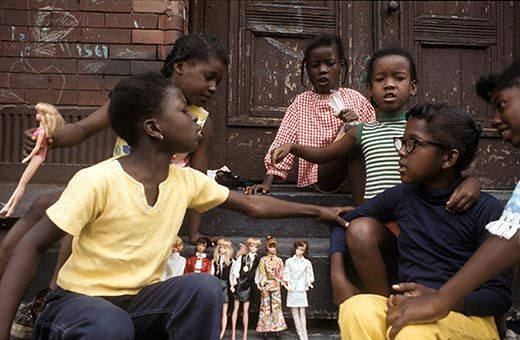

Getting it, for Vergara, involves a certain amount of detachment. There is an almost clinical quality to some of his work. He chooses not to focus excessively on images of poor people, however engaging or emotional such pictures can be, because they establish a false sense of connection between viewer and subject. “I found that images of the physical communities in which people live better reveal the choices made by residents,” he wrote in a 2005 essay.

Vergara knows about poverty first-hand. His own family background made him “a specialist in decline,” he says.

Born in 1944 in Rengo, Chile, in the shadow of the Andes, Vergara says his once-wealthy family exemplified downward mobility. “We always had less and less and less,” he says. “It got pretty bad.” Coming to the U.S. in 1965 to study at Notre Dame University only reinforced his sense of dispossession. Other kids’ parents would come to visit in station wagons, throw huge tailgate parties and get excited about a kind of football he had never seen before. “So I was a stranger, as complete a stranger as you can be,” he says. “I couldn’t even speak in my own language.”

He found himself gravitating to the poorer sections of town, and when he traveled to blue-collar Gary, Indiana, he found “paradise,” he says—“in quotation marks.” Vergara eventually came to New York City to do graduate work in sociology at Columbia University, and soon thereafter began exploring Harlem and taking pictures, an endeavor that has taken him coast-to-coast many times since, tending the ground he has staked out.

“It’s the immigrant that wants to possess the country that’s not his,” he says. Through his pictures, Vergara says, “I have these little pieces—banks, old cars, homeless shelters, people getting arrested. It’s like I am a farmer, I have all of these things. They are what has given me citizenship.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)