The Healing Power of Greek Tragedy

Do plays written centuries ago have the power to heal modern day traumas? A new project raises the curtain on a daring new experiment

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/9c/f39cb745-e3fa-4282-8455-9667a173bcb2/antigoneferguson021.jpg)

Make them wish they’d never come, the director says, almost absently. He means the audience. The actress nods. She makes a mark in her script next to the stage direction:

[An inhuman cry]

And they go on rehearsing. The room is quiet. Late afternoon light angles across the floor.

An hour later from the stage her terrible howl rises over the audience to the ceiling, ringing against the walls and out the doors and down the stairs; rises from somewhere inside her to fill the building and the streets and the sky with her pain and her anger and her sadness. It is a terrifying sound, not because it is inhuman, but because it is too human. It is the sound not only of shock and of loss but of every shock and of every loss, of a grief beyond language understood everywhere by everyone.

The audience shifts uncomfortably in their seats. Then silence covers them all. This is the moment the director wanted, the moment of maximum discomfort. This is where the healing starts.

Later, the audience starts talking. They won’t stop.

“I don’t know what happened,” the actress will say in a few days. “That reading, that particular night, broke open a lot of people. And in a great way.”

This is Theater of War.

The creation of director and co-founder Bryan Doerries, Brooklyn-based Theater of War Productions bills itself as “an innovative public health project that presents readings of ancient Greek plays, including Sophocles’ Ajax, as a catalyst for town hall discussions about the challenges faced by service men and women, veterans, their families, caregivers and communities.”

And tonight in the Milbank Chapel of Teachers College at Columbia University, they’ve done just that, performing Ajax for a roomful of veterans and mental health professionals. Actor Chris Henry Coffey reads Ajax. The scream came from Gloria Reuben, the actress playing Tecmessa, Ajax’s wife.

Sophocles wrote the play 2,500 years ago, during a century of war and plague in Greece. It was part of the spring City Dionysia, the dramatic festival of Athens at which the great tragedies and comedies of the age were performed for every citizen. It is the wrenching story of the famed Greek warrior Ajax, betrayed and humiliated by his own generals, exhausted by war, undone by violence and pride and fate and hopelessness until at last, seeing no way forward, he takes his own life.

**********

Doerries, 41, slim and earnest, energetic, explains all this to the audience that night. As he sometimes does, he will read the role of the chorus, too. He promises that the important work of discovery and empathy will begin during the discussion following the reading. The play is just the vehicle they’ll use to get there.

A self-described classics nerd, Doerries was born and raised in Newport News, Virginia. His parents were both psychologists. A smart kid in a smart household, he appeared in his first Greek play at the age of 8, as one of the children in Euripides’ Medea. He’ll tell you it was a seminal experience. “I was one of the children who were killed by their pathologically jealous mother—and I still remember my lines and the experience of screaming them, belting them backstage while a couple of college students pretended to bludgeon me and my friend. And I remember the sort of wonderment, the sense of awe, of limitless possibilities that the theater presented and associating that with Greek tragedy at a very early age.”

He was an indifferent high school student who bloomed in college. “My first week as a freshman at Kenyon, I met with my adviser—who just happened to be a classics professor assigned to me—and decided to take ancient Greek.

“I learned to commit to something hard and that it would result in incredible dividends. And so that’s when I started adding other ancient languages and doing Hebrew and Latin and a little Aramaic and a tiny bit of German and having this classical education that was about a deep dive into language, and the sense of early Greek thinking.” For his senior thesis he translated and staged Euripides’ The Bacchae.

He might have gone on to a fine and forgettable career as an academic; a philologist. But his origin story is more complicated than that, as most origin stories are, and has at its heart a tragedy.

In 2003, following a long illness, Doerries’ girlfriend, Laura, died. In the weeks and months of grief that followed he found comfort where he expected none: in the tragedies of ancient Greece. He was 26. All of which he explains in his remarkable 2015 book The Theater of War.

The Theater of War: What Ancient Tragedies Can Teach Us Today

This is the personal and deeply passionate story of a life devoted to reclaiming the timeless power of an ancient artistic tradition to comfort the afflicted. For years, theater director Bryan Doerries has led an innovative public health project that produces ancient tragedies for current and returned soldiers, addicts, tornado and hurricane survivors, and a wide range of other at-risk people in society.

“Although I wasn’t aware of it at the time, witnessing Laura’s graceful death opened my eyes to what the Greek tragedies I had studied in school were trying to convey. Through tragedy, the great Athenian poets were not articulating a pessimistic or fatalistic view of human experience; nor were they bent on filling audiences with despair. Instead, they were giving voice to timeless human experiences—of suffering and grief—that, when viewed by a large audience that had shared those experiences, fostered compassion, understanding and a deeply felt interconnection. Through tragedy, the Greeks faced the darkness of human existence as a community.”

But that’s the book version. Tidy. Well-considered. The truth of it was messier.

Coming out of graduate school in California, he was scrambling. He had moved to New York and was writing and translating in an apartment above the Tops grocery store on Sixth Street in Williamsburg. Laura had been diagnosed with cystic fibrosis years before, and now, after medical interventions, including a double lung transplant, it was apparent she wouldn’t make it. She made her peace with it and shared that peace and for weeks was visited by the people she loved most, and who loved her. And the experience of her death at the age of 22 was thus somehow touched with joy.

“And the way that she died, which could be viewed as very sad, was actually one of the most powerful and transcendent and important moments of my life. That anyone could die this way was something I didn’t understand at age 26. It was a revelation.

“After that experience and caring for my father through his kidney transplant, I started working on Philoctetes and remember writing the chorus in the hospital where my father was recovering, thinking to myself that I’ll never get out of the transplant ward of the hospital. And it was dawning on me that the reason I was translating Philoctetes was it was specifically about a chronically ill individual abandoned on an island. And, even more poignantly, about a young person who against his will, without really knowing what he’s getting himself into, is thrust into this epically impossible situation as a caregiver. For which there aren’t right answers and by which he’s going to be haunted for the rest of his life.

“What happened was, I think, precisely what the Greeks were trying to prepare young people for, through tragedy, which is the exigencies of adult life.

“And when Laura died, all I wanted to do was talk about these big existential things, about death and what I witnessed. I really think that this apparatus that I created is really just a giant pretext to create this space where people will want to talk about this.”

This is Doerries’ magnificent obsession, the solace of history. Restarting an ancient machine for healing; the living theater as a therapeutic instrument.

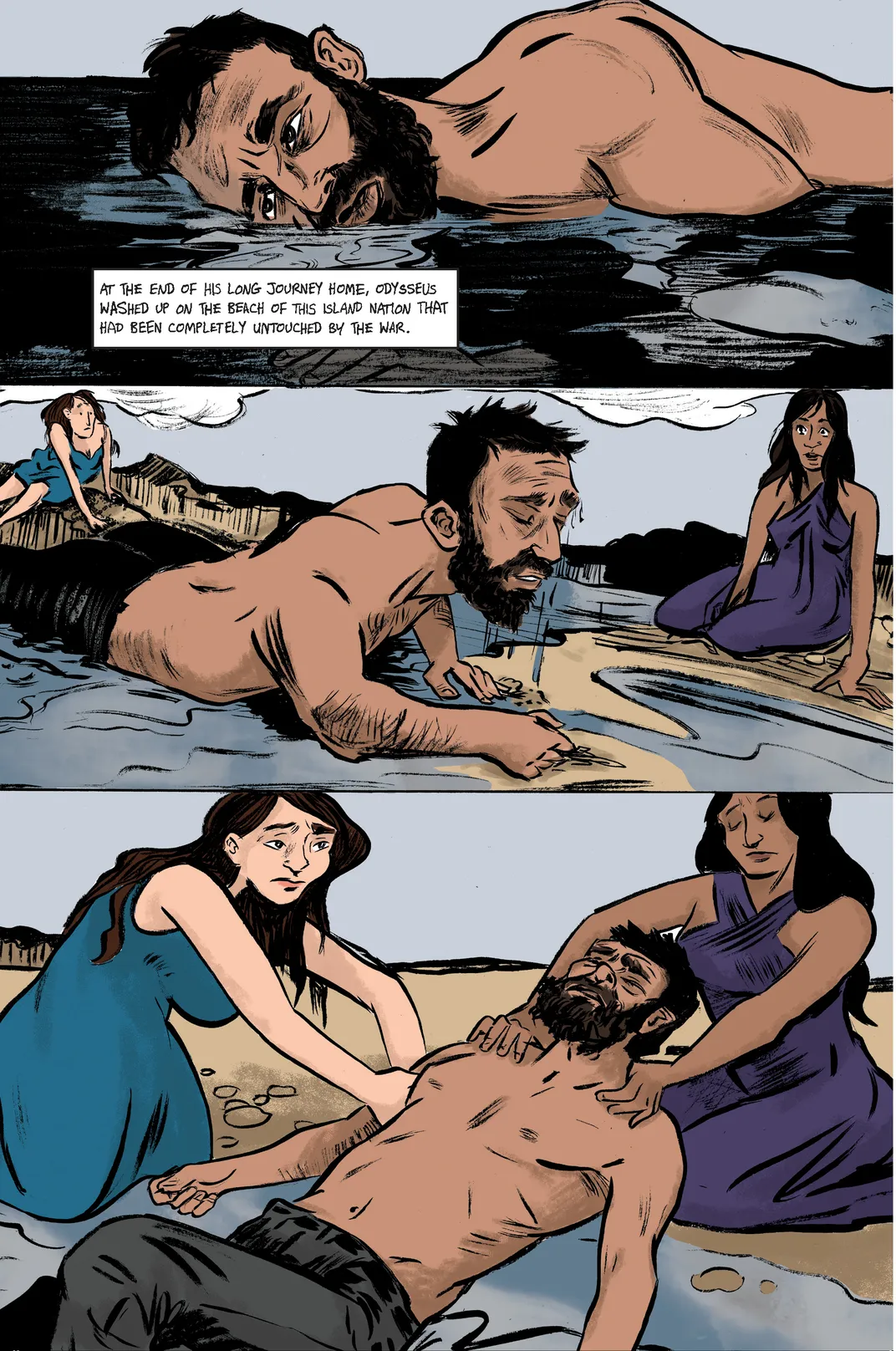

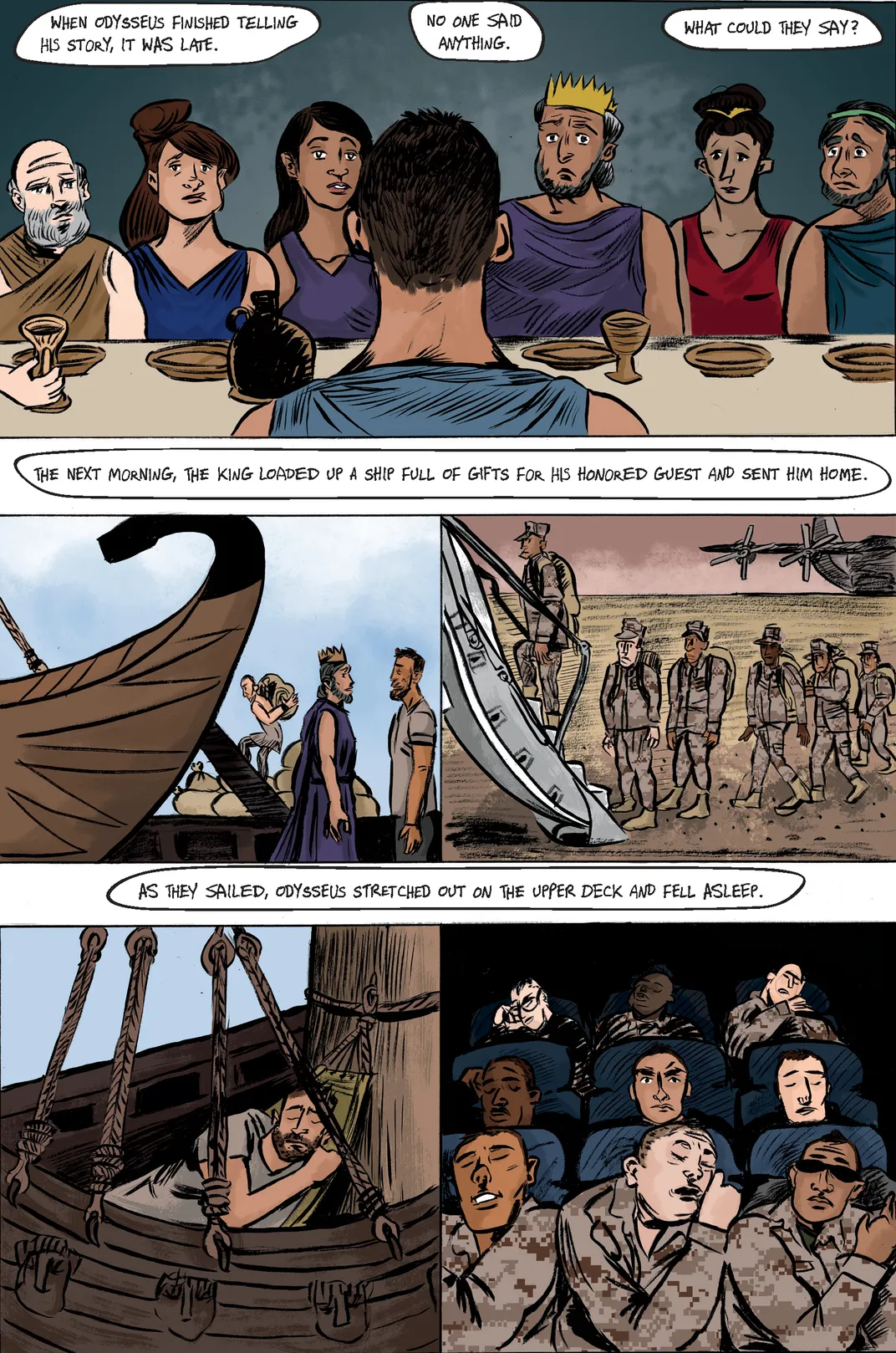

His translations of Ajax and several other canonical works of the Greek theater are collected in All That You’ve Seen Here Is God, also published in 2015. His latest book, The Odyssey of Sergeant Jack Brennan, an updated adaptation of The Odyssey, should probably be in the hands of every soldier everywhere for lessons it teaches about loss, loneliness and post-traumatic stress.

And for a man who spends 100 nights a year on the road, who has produced and directed hundreds of shows in the last eight years, who has published five books in the last two years, Bryan Doerries does not look drawn or haggard or tired. Whenever you see him, Bryan Doerries looks ready.

**********

By sharing all this, by helping himself, he figures he can help the rest of us. And that core value of Theater of War is here, in a single line in Ajax, from this early exchange between the chorus and Tecmessa:

TECMESSA

Tell me. Given the choice,

which would

you prefer: happiness

while your friends

are in pain or to share in

their suffering?

CHORUS

Twice the pain is twice as worse.

TECMESSA

Then we’ll get sick while he recovers.

CHORUS

What do you mean? I do not follow the

logic of your words.

TECMESSA

In his madness he took pleasure in the evil

that possessed him, all the while afflicting

those of us nearby. But now that the fever has

broken all of his pleasure has turned to pain,

and we are still afflicted, just as before.

Twice the pain is twice the sorrow.

CHORUS

I’m afraid that some god struck him down,

for his anguish grows as his sanity returns.

TECMESSA

It is true, but still hard to understand.

CHORUS

How did the madness first take hold of him?

Tell us. We will stay and share in the pain.

“Tell us. We will stay and share in the pain,” is the premise for the entire program, as Theater of War’s own mission statement makes clear.

“By presenting these plays to military and civilian audiences, our hope is to destigmatize psychological injury,” Doerries tells his audience. “It has been suggested that ancient Greek drama was a form of storytelling, communal therapy and ritual reintegration for combat veterans by combat veterans. Sophocles himself was a general. The audiences for whom these plays were performed were undoubtedly composed of citizen-soldiers. Also, the performers themselves were most likely veterans or cadets.

“Seen through this lens,” he continues, “ancient Greek drama appears to have been an elaborate ritual aimed at helping combat veterans return to civilian life after deployments during a century that saw 80 years of war. Plays like Sophocles’ Ajax read like a textbook description of wounded warriors, struggling under the weight of psychological and physical injuries to maintain their dignity, identity and honor.”

Theater of War Productions has presented more than 650 performances for military and civilian audiences all over the world, from Guantánamo to Walter Reed, from Japan to Alaska to Germany. Doerries has employed other plays from ancient Greece to serve other purposes as well, addressing issues such as domestic violence, drug and alcohol addiction, gun violence and prison violence. Presentations can be tailored for service members, veterans, prison guards, nurses, first responders, doctors and police officers.

What the programs do in every case is crack you open.

Even these minimalist table readings engage people in a way they’re unprepared for. “The performances are always incredibly cathartic,” says Chris Henry Coffey, who has collaborated frequently with Doerries. “It touches on something Bryan says, ‘If there’s one thing you take away from this tonight, it’s that you are not alone. You’re not alone in this room, not alone in the world and across miles, and most importantly, not alone across time.’”

What did Sophocles know that we don’t? That drama, live theater, can be a machine for creating empathy and community.

Emmy winner and Academy Award nominee David Strathairn, lean and quiet and decent, was one of Doerries’ first actors. “What is extraordinary about what Bryan conceived, and is proven every time we present, is that these plays don’t need the accoutrements of a staged production to be effective. No lights, no costumes, no set, no musical enhancement. The story is delivered raw and unadorned directly to the ears of the audience. And as Bryan has said many times, the real drama begins once the reading is finished and discussion begins.”

Actors are paid a small honorarium, fly economy and stay at the two-star hotel chains.

“I speak to those who understand!” says Ajax, nearing the end of things. It is the veteran’s lament, that the story can be understood only by those who have seen the same things. But it turns out that’s not true; that all of us in the tribe can contribute our understanding as therapy; as medicine.

What’s more heartbreaking even than his anger or shame or self-pity is his ambivalence in his last quiet moment. Mourning himself already and what he’ll leave behind.

AJAX

Death oh Death, come now and visit me—

But I shall miss the light of day and the

sacred fields of Salamis, where I played

as a boy, and great Athens,

and all of my

friends. I call out to you springs and rivers

fields and plains who nourished me during these

long years at Troy.

These are the last words you will hear Ajax speak.

The rest I shall say to those who listen

in the world below.

Ajax falls on his sword.

A few seconds later, his wife Tecmessa finds him and sets loose her terrible cry. That cry echoes down 2,500 years of history, out of the collective unconscious. Men and women and gods, war and fate, lightning and thunder and the universal in everyone.

**********

The United States has been at war for 16 years. Soldiers in the past might be deployed for 100 days or even 300 days in a frontline war zone; now they’ve been downrange 1,000 days or more. Four, five or six tours in Iraq or Afghanistan or both. The stresses are unbearable. Armed forces suicide rates have never been higher. A Department of Veterans Affairs study was released in 2016. As reported by the Military Times:

“Researchers found that the risk of suicide for veterans is 21 percent higher when compared to civilian adults. From 2001 to 2014, as the civilian suicide rate rose about 23.3 percent, the rate of suicide among veterans jumped more than 32 percent.

The problem is particularly worrisome among female veterans, who saw their suicide rates rise more than 85 percent over that time, compared to about 40 percent for civilian women.

And roughly 65 percent of all veteran suicides in 2014 were for individuals 50 years or older, many of whom spent little or no time fighting in the most recent wars.”

Retired Army Gen. Loree Sutton, a medical doctor and commissioner of the Department of Veterans Services for the city of New York, was an early advocate of Theater of War.

“I had been through so many sorry training sessions with PowerPoint slides. We had to have something that would really engage our troops and their leaders. An experience that really spoke to their inner fears, needs and struggles.

“I first met Bryan at the Defense Centers of Excellence inaugural Warrior Resilience Conference in 2008,” recalls Sutton. “It was Elizabeth Marvel, Paul Giamatti and Adam Driver for that initial performance. I was blown away. One officer told me—I’ll never forget this—he had recently lost a buddy to suicide. He said, ‘I just know...I just know my buddy would be here today if he had seen that you can have these feelings, these struggles and you can still be the strongest of warriors.’”

“I really took that as an endorsement of Bryan’s model,” adds Sutton. “I started talking to Bryan and trying to figure out, how could we bring this to scale throughout Department of Defense? Against all odds, we were able to negotiate a contract with DoD. This has led to Ajax being so broadly shared in so many different settings and groups.”

But that initial contract funding has now run out. The challenge for Doerries is raising not only awareness but money. And at a time when veterans are being asked to return their re-enlistment bonuses, that’s no easy task. According to the Pentagon, the Pentagon is strapped.

“Theater of War has been part of my journey,” says Lt. Col. Joseph Geraci, co-founder of the Resilience Center for Veterans & Families, a privately funded initiative at Columbia University. “It’s the therapy I’ve received in its cathartic moments that help me feel connected to the person to my left and my right.

“My purpose is to help others heal,” he says. “I still get goose bumps whenever Bryan mentions that the intent of the evening is to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.”

“No one gets closer to a text or the impulse behind the language itself than actors and an audience,” Doerries says. He directs at just one tempo, prestissimo. Performed at Doerries’ ideal pace, it’s almost anti-theatrical: the urgency has a basis in brain chemistry. The discomfort he seeks triggers the fight or flight mechanism in the listener, heightening not only their dramatic apprehensions but their senses. Their attention. Their retention. You walk out of the best of these shows exhausted.

And maybe you’ll walk somewhere to get help.

The show is not a talking cure. It is not an end in itself.

It is the beginning. And right now someone somewhere needs them. Needs this.

**********

That’s how they got to Ferguson, Missouri.

On August 9, 2014, Michael Brown, 18, was shot to death during an altercation with police officer Darren Wilson. Ferguson became synonymous with violent unrest and militarized police, with Black Lives Matter and new social justice and old urban stereotypes of us versus them. The very name Ferguson, like Watts or Newark or the Lower Ninth Ward, became a sound bite, another shorthand for injustice and struggle, for a set of seemingly fixed assumptions about America and Americans.

Theater of War arrives trying to change that.

“When Michael Brown died,” Doerries says, “Christy Bertelson, the head speechwriter for Governor Jay Nixon, called me to see if I could think of a play that would help. Eventually I proposed Antigone. It was Christy who suggested we set the choruses to gospel, and then I insisted that we build a choir that included police singers.”

Landing in St. Louis, Doerries is tired. He is also hungry. He is also on his phone. He answers questions as he walks, his rolling luggage at his heels like a devoted family pet. In other words, he is as he always is. Avid, and in motion.

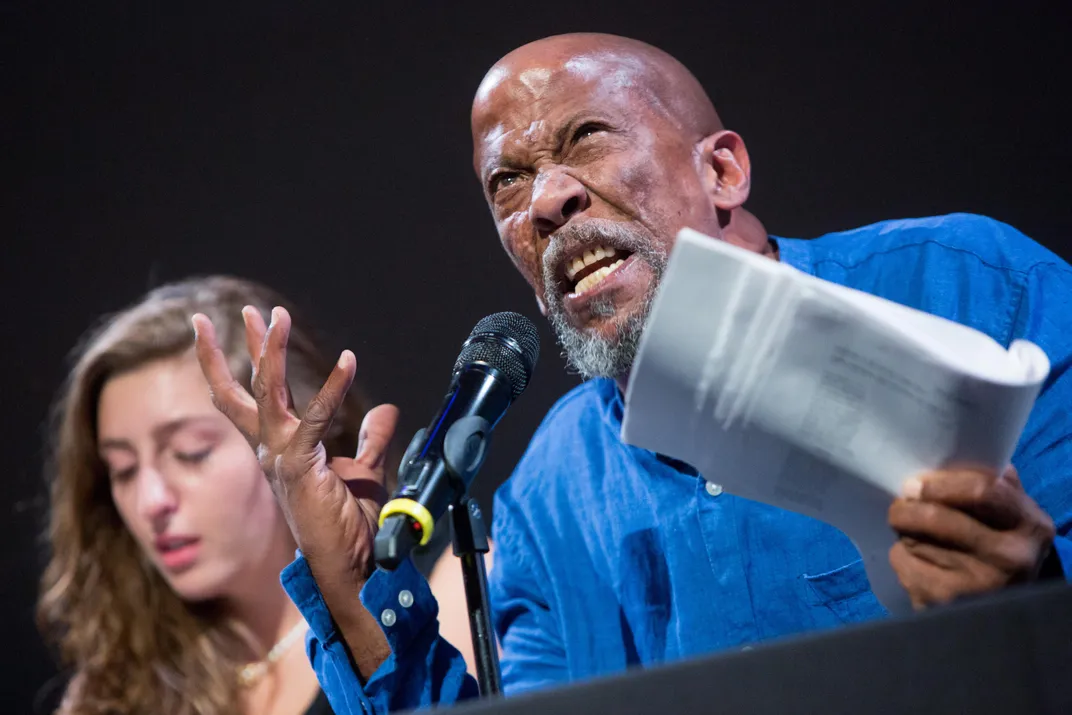

The Greek chorus will be played by an all-star gospel choir from several area churches, a youth choir, and the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department Choir. The music has been composed by Phil Woodmore, a local music teacher and musician and singer of renown. “I created all five of these songs based on the flow of the story and the text that Bryan had given me. Even in the challenge of it, there was so much structure around it. So there was still a safe zone there for me.”

Reg E. Cathey (“House of Cards,” “The Wire”), with the voice of an Old Testament prophet, will strut and fret as Creon. At rehearsal in a classroom at Normandy High School, actress Samira Wiley (Poussey Washington in the Netflix series “Orange Is the New Black”) is as fierce as Antigone must be. In the scene when she is told that she’ll never get where she wants to go, her delivery of the line “Then I shall die trying” brings not only chills but tears. Even the TV news crew in the room is brought up short by it.

Glenn Davis (“Jericho,” “The Unit,” “24,” Broadway) and Gloria Reuben (“ER,” “Mr. Robot”) will play a variety of roles.

There will be three performances in a single day. One at Normandy High School, two more at Wellspring Church. Understand first that Ferguson isn’t a war zone. It’s a St. Louis suburb of mixed incomes, mixed outcomes, mixed demographics. Wells-Goodfellow, the neighborhood down the road by the high school, isn’t a war zone either. It’s what a city looks like after the war is lost. Picture Berlin in 1950 black-and-white. The debris has been bulldozed and what’s left is a tidy grid of mostly empty buildings and lifeless sidewalks.

It’s an apt setting for Antigone. It’s a play about violence and authority and sadness and about the high price of principle and the impossible cost of weakness. It’s a play about an unburied body.

A terrible civil war has just ended in Thebes. Antigone’s brothers have killed each other and died in each other’s arms. Creon has taken the throne and ordered the rebellious brother, Polyneices, be left to rot unburied. Defying that order, Antigone rushes to bury him.

CREON

Tell me—and be careful with your words—

were you aware of my proclamation forbidding

the body to be buried?

ANTIGONE

Yes. I knew it was a crime.

CREON

And you still dared to break the law.

ANTIGONE

I didn’t know your laws were more powerful than

divine laws, Creon. Did Zeus make a proclamation,

too? I wasn’t about to break an unwritten rule of

the gods on account of one man’s whim. Of course,

I knew I would some day die. And if that day is

today, then I count myself lucky. It is better to die

an early death than live a long life surrounded by

evil men. So don’t expect me to get upset when you

sentence me to death. If I had allowed my own brother

to remain unburied, then you might see me grieving.

What’s wrong? You seem puzzled. Perhaps you think

I’ve rushed to action without considering the

consequences? Well, maybe it’s you who has rushed to

action. Either way, the question remains: Do you have the guts

to follow through?

CREON

I see you’ve inherited your father’s charm.

Citizens, I say that she is a man and I am not,

if she gets away with breaking the law and boasting

about her crime. I don’t care if she’s my niece, she

and her sister will both be put to death, for

I hold her sister equally responsible for planning

this burial. Call her. She’s right inside. I just saw

her running around the palace in hysterics.

Creon orders Antigone put to death, walling her up in a small cave where she eventually commits suicide. As does Creon’s own son, betrothed to marry her. Then Creon’s wife, when she learns of her son’s death. It is a chain of tragedies forged by Creon’s own stubbornness.

Antigone wants only to do what’s right, bury her brother. Creon wants only to do what’s right, preserve civic order. It’s a play, as Doerries instructs the audience, “about what can happen when everyone is right.”

The breakneck pace of these readings gives the events of each play a drumbeat not only of urgency but of inevitability. The price of good fortune is calamity, and it is swift-moving and it is inexorable, and as the chorus says, destiny can be avoided, but it cannot be escaped. Fate is a one-track, high-speed train wreck, and for the audience, this means a swift rush of endorphins.

The translations are part of the effect and the program’s success, too. Most textbook translations of these Greek classics, the ones dreaded by high school students, read like a 19th-century catalog of waxworks. Here’s Ajax, perfectly preserved and standing absolutely still; here’s Odysseus, here’s Achilles. The heroes cast shadows, but nothing moves. More devoted to scholarship and preservation than the imperatives of living theater, the whole thing is inert on the page. Even the best modern versions lose dramatic momentum in the bogs and thickets of their own poetry.

But every Doerries translation is a hot rod. A souped-up, stripped-down engine of event. Behavioral rather than aesthetic, each one is a master class in compression; in conflict and climax and American vernacular English. Lives are ruined and race to their inevitable end without the ornamentations of poetry. “To me it’s one thing. Directing and translating are one thing.” The last few lines of Antigone illustrate the point.

Creon has been destroyed by fate, by his own convictions and decisions. He begs to be led away from the city.

The Doerries translation, spare and unsentimental, is a punch in the face.

CREON

Lead me out of sight, please...I am a foolish man.

There’s blood on my hands. I killed my wife and child.

I am crushed. I have been crushed by fate.

exit Creon.

CHORUS

Wisdom is the greatest gift to mortals. The grand

words of proud men are punished with great blows. That

is wisdom.

At the moment of that last line the theater is hushed with a terrible truth.

And it arouses in people the willingness to rise and speak and to share their suffering.

One of the singers, Duane Foster, a speech and drama teacher, is also a panelist, and taught Michael Brown. He leans into the microphone and his anger is not measured, it is righteous. “So many people look at the actual act of the shooting. People forget about the total blatant disrespect of that boy laying on the ground because people were trying to figure out what to do.”

What does Sophocles know that we don’t?

“You are standing in front of people,” Samira Wiley told a film crew from PBS after the performance. “You are looking at people who were in this young man’s class, people who were his educators. And what we do, at the end of the day, is fake. It’s—we’re acting. But we can elicit real, emotional human feelings from people. And one thing that Bryan Doerries told me was that it’s not so much about what we can give them, but what they can give us. And you can hear that in theory, but I really experienced that today.”

Two shows at the church in the heat, the music rising, the audience taken up, cops and community, the intimacy and the ardor and yes, the love, even in dispute or disagreement, everyone for everyone, neighbors again, so sweetly, so briefly, unopposed. All the sweat and ecstasy and chain lightning of an old-time revival meeting.

“It was this amazing little moment, both artistic and communal,” Reg E. Cathey says. “Black people, white people, old people, young people. It was one of those things that make you glad to be an American in a weird way.”

“When I had my first rehearsal with a choir, I felt this was working, but I did not expect that level of a response,” Phil Woodmore said. “I knew that what I had created was a very well-packaged product that people could appreciate, but I did not know how overcome people were going to be.”

Late that night, even an exhausted Doerries is overwhelmed. “It was more than I had imagined for it,” he said, “Even after rehearsal I couldn’t know what that music would do to an audience. Amazing. Now we take this show on to Baltimore and New York.”

Beyond class war and political resentment, beyond even racism, there is something profoundly lonely in modernity, something isolating and dislocating. Maybe sitting in the same room with other humans who suffer and speak is comfort enough. Maybe enough to save us.

The next morning, sunrise early, singer John Leggette, a police officer who performs as a soloist in the chorus, is back in uniform. But his heart is still on stage.

“That was awesome,” he says, smiling and shaking his head and walking slowly to his squad car. “Awesome.”

**********

A few months later, in the auditorium of the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C., sit the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

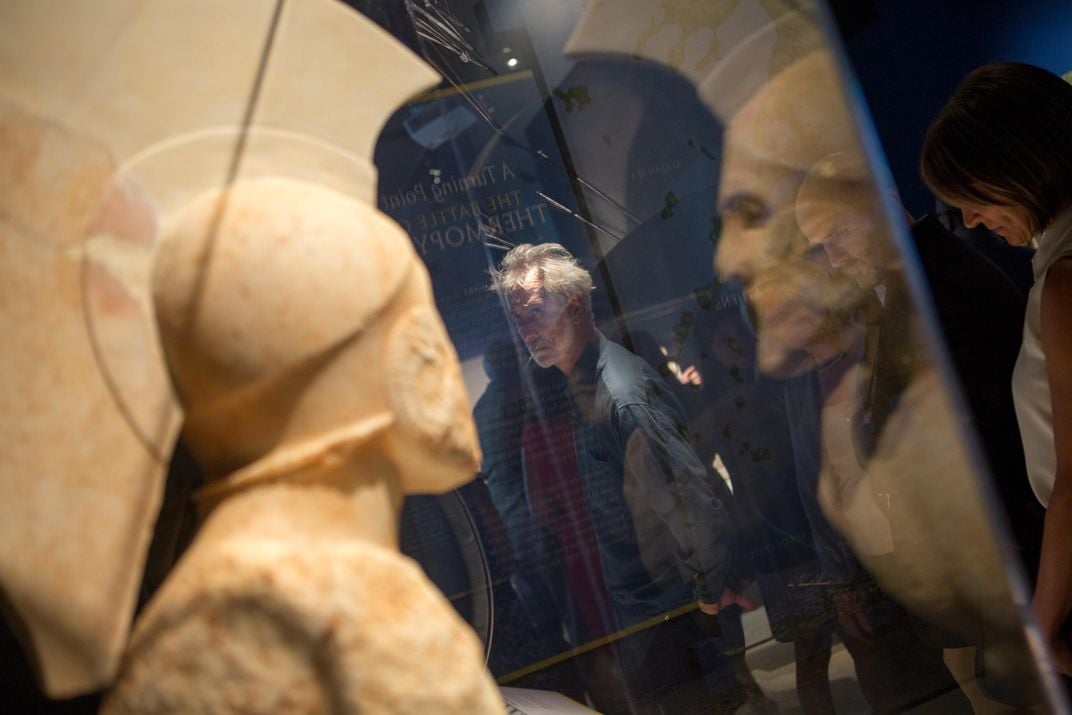

Before the performance, the actors walk through a touring exhibition of Greek antiquities in the National Geographic Museum. David Strathairn spends a long moment looking hard at a great hammered disk of gold. The face on the disk is his own, straight-featured and serious. “Well, let’s just say that seeing the Mask of Agamemnon before reading a play written 2,500 years ago that speaks directly of that time in history, to a room full of people intimately acquainted with what it means to be a warrior, was a pretty heady experience. Time dissolved for a moment—The ‘here and now’ met ‘the then and there.’”

One of the leads, Jeffrey Wright, isn’t here yet. His plane is late. He’ll arrive at 5:05 for a 5 o’clock show.

For the other actors—Strathairn in the role of Philoctetes, Cathey as Ajax and Marjolaine Goldsmith as Tecmessa, his wife—the instruction in rehearsal remains the same: Make the audience wish they had never come.

And again Tecmessa begins,

Oh, you salt of the Earth, you sailors who serve Ajax,

those of us who care for the house of Telamon will soon

wail, for our fierce hero sits shellshocked in

his tent, glazed over, gazing into oblivion.

He has the thousand-yard stare.

CHORUS

What terrors visited him in the night

to reverse his fortune by morning?

Tell us, Tecmessa, battle-won bride, for no one is

closer to Ajax than you, so you will speak as one

who knows.

TECMESSA

How can I say something that should never

be spoken? You would rather die than hear

what I am about to say.

A divine madness poisoned his mind,

tainting his name during the night.

Our home is a slaughterhouse,

littered with cow carcasses and goats

gushing thick blood, throats slit,

horn-to-horn, by his hand,

evil omens of things to come.

“Our home is a slaughterhouse,” is the line that military wives and husbands in the audience and on the panels most often mention, the one that cracks them open with a terrible recognition. The play is as much about the challenges facing the spouses, the families, as it is about the wounded fighter, the isolated, brokenhearted hopeless.

So into this sedate wood-paneled room are beckoned all the horrors of war. Doerries, in a dark, well-cut suit, is up and down the aisles with a microphone as soon as the reading is over.

He asks the audience a question about Ajax: “Why do you think Sophocles wrote this play?” Then he tells a favorite story. “I asked that question at one of our first performances and a young enlisted man stood up and said, ‘To boost morale.’ And I thought, ‘That’s crazy’ and I asked him what could possibly be morale-boosting about a great warrior descending into madness and taking his own life?

“‘Because it’s the truth,’ he said. ‘And we’re all here watching it together.’”

Joe Geraci is again on the panel here, and tells a wrenching story. “In 2007, in July, I buried one of my best friends in Arlington. The hardest thing for us that day was that every single one of us would have given our life if Tommy could have come home alive. I haven’t been back there in about nine years. So today I went to Section 60. I placed one of my battalion coins on his gravestone and I was weeping and I looked up and saw another one of my close friends, who was also in Section 60—he was one of my bunkmates during my last deployment to Afghanistan—and we just embraced. We just embraced for like five minutes. No words exchanged. And I’m recalling Tecmessa’s message of, ‘We’ll get sick while he recovers,’ so undoubtedly me and Bryan got a little sick today, and I know my parents got a little sick today, but I was able to heal.”

Then a man rises in the audience and takes the microphone and says in a soft voice, “First I want to thank the actors and thank our panel members. My name is Lieutenant Colonel Ian Fairchild. I’m a C-130 pilot. I have flown in Afghanistan and Iraq. To answer your question, ‘Why do they take it to that extreme, 15 or 20 minutes of wailing?’ I think that he probably did it that way because that’s the only way, comparatively, for his audience, it must have seemed awful, and horrible, and that really would have brought the message home. But for the people who have served, it probably did not compare on any level. And then personally what really struck me about the wailing is that more powerful than wailing is the silence that covers you when you come to your aircraft and you see an American in a flag-draped casket and you have to fly them home in silence. That to me is more powerful than any scream. So, thank you very much for the performance this evening and for the chance to have this conversation.”

And the room goes quiet for what feels like a very long time.

**********

After the show, at the reception, vets from the audience were still thinking and talking about what they’d seen. It’s a beginning. Not an end.

How do we reintegrate our soldiers—and ourselves—into a healthier society?

To say that the effect is cathartic or therapeutic is to understate things by an order of magnitude. Those screams. The human agony. The effect is that of being split down the middle, not at the weakest parts of yourself, but at the strongest. Things pour out, and things pour in. It is a machine for healing, for making empathy.

The quality of the performance, however superb, is secondary. The discussion is why these folks are here, and that chance for healing and connection and intimacy. Go often enough, long enough, and you’ll see soldiers rise in tears, and husbands speak of wives, and sons and daughters tell the stories of their mothers and fathers.

A month after the presentation at National Geographic, the then Secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Robert A. McDonald, who was seated in front that night, tells Doerries that he thinks there’s a way to scale Theater of War into a national program. The Veterans department is probably where it belongs. But Washington is a wheel that grinds slow, and anything can still happen. But “this bodes well,” Doerries says, “and this only adds to our groundswell of momentum.”

In addition, Doerries has proposed that the Department of Defense consider an initiative to provide newly inducted members of the military with a copy of Doerries’ The Odyssey of Sergeant Jack Brennan. The graphic-novel retelling of The Odyssey by a Marine sergeant to his squad the night before they rotate stateside, succeeds as art and instruction. It is a primer on the struggle and isolation every soldier since the beginning of time has faced on the way home. It connects soldiers not only to the experience of war but to its psychological costs and to history itself.

Today, however, when spending cuts may loom, even popular projects lose momentum. Who’s in, who’s out, who’ll write the checks? And it’s the same at Veterans Affairs as at the Defense Department. What the future holds for large-scale implementation of the books or workshops or performances is unknown.

A Theater of War performance, Doerries says, would be held “for all the Joint Chiefs and the Secretary of Defense and everyone below them, which would be hosted by the chairman and his top staff.” The date for the event was set for October 4 at Fort McNair in Washington, D.C.

**********

A few months after the original Ferguson production, another performance of what is now called Antigone in Ferguson was mounted in New York City, in the atrium of a skyscraper on Fifth Avenue. Most of the singers and performers are the same, but the setting couldn’t be more different. The night is part of the Onassis Festival NY, “Antigone Now,” a celebration of Greece and Greek culture and history produced by the Onassis Foundation.

The space is a block long, tall and narrow, hung with lights and speakers and temporary staging. Sound ricochets off everything. There are chairs for 100 audience members and standing room for a few hundred more. The crowd is a New York City mix of men and women of all ages and colors and classes and languages. The choir is off to one side, rather than behind the actors, and once the singing starts, the entire atrium is filled with music. And before the night is over, you’ll see the panelist who hates police, who fears for the lives of her black sons at the hands of police, gather up the police lieutenant in her arms and not let go.

Again, Samira Wiley is fierce as Antigone. Actors Glenn Davis and Gloria Reuben are grounded and honest; they bracket Reg E. Cathey as he roars and gets steamrolled by fate. Again, the music soars. Again the night is ecstatic in the truest sense, nearly hypnotic, with the spirit in words and music moving through everyone. But even in this sanitized corporate setting, once the discussion starts the tension is between hope and hopelessness.

“What are the effects of segregation on policing?”

“What about stop and frisk?”

“How do you defend what is obviously wrong?”

And again, Duane Foster is ardent, and Lt. Latricia Allen is the reasonable voice of responsible policing. She doesn’t believe in the blue wall of silence. “I have to be the change I want to see,” she says. “I don’t go along with the okey-doke.”

The discussion goes on and on, about the nature of respect and disrespect; about the relationship between police and the people they’re meant to serve; about parents and violence and politics and fear and love.

Doerries reminds everyone that tonight is only a beginning; they’ll carry the conversation out into the wider world. One of the last questions is one of the simplest. And most complicated. “I’m African-American,” a woman says in a level tone that rises in the polite silence. “How are we supposed to live?” And for a long time that question sifts down over everyone. It is the question at the center of everything. And for a while the panel gives well-meaning answers touched with optimism, but the question is too grave, too planetary. The answers wander and stop.

How are we supposed to live?

Then Duane Foster leans forward.

“Shit ain’t right,” he says finally, decisively, “but you can’t give up. The God I serve does really weird things to make a point.”

And the room fills with applause.

A few days later, Bryan Doerries will say the actors and the panelists and the musicians and the members of the chorus “were delighted to discover that we had the power to turn even a corporate lobby into a church.”

**********

In the meantime, Antigone in Ferguson is for the moment a fully funded hit, a runaway success from Baltimore to Athens, Greece, underwritten in part by Doerries’ recent appointment as a public artist in residence for the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs. Operating for the next couple of years on a grant of $1.365 million donated by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, Doerries sees the sudden and unexpected popularity of this show as a first step toward a more permanent home for Theater of War performances.

“The next phase of this project is to resocialize audiences to expect something different of the theater,” Doerries says. “It’s really turning New York City into this laboratory, so it’s kind of a dream come true.”

In that way Ajax begets Prometheus begets Medea begets Hercules in Brooklyn, taking Euripides into the streets to talk about gun violence. And also new for 2017 is The Drum Major Instinct, another show with a gospel choir and a score by Phil Woodmore. Based on one of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s final sermons, the production wrestles questions of racism and inequality and social justice.

So the success of its Antigone is pushing other Theater of War productions into the cities and neighborhoods where they’re needed most, into the libraries and shelters and housing projects and community centers, into the lives of audiences in real need of their ancient message of consolation, reconciliation and hope.

The future of the past is bright.

**********

Out of suffering, hope. Maybe that’s what Sophocles knows—that Ajax and Tecmessa and Creon and Antigone suffer and speak for us all, so that we too might suffer and speak.

Twenty-five hundred years later, that terrifying cry comes back to you not only as an echo through time, or a theatrical antique, but as an expression of new grief and fresh loss as near and familiar as your own voice. Because it is your own voice.

“Make them wish they’d never come.”

But here we are. Every one of us.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)