Historical Laughter

Those who don’t have power tend to make fun of those who do. But what happens when the power shifts?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Presence-Lytton-Strachey-631.jpg)

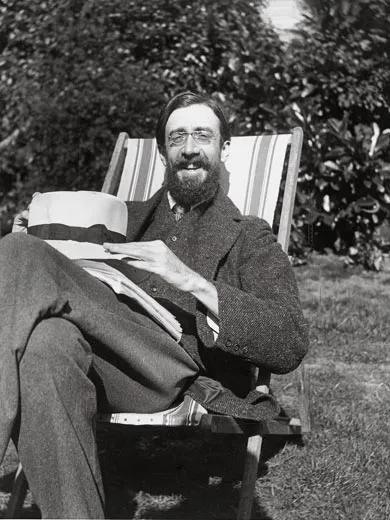

Lytton Strachey made up the business about Thomas Arnold having short legs. Arnold—headmaster of Rugby, father of Matthew Arnold, paragon of manly 19th-century Christian rectitude and one of the subjects of Strachey's Eminent Victorians—had perfectly normal legs.

But Strachey, for his own sly purposes, invented the indelible detail: "[Arnold's] outward appearance was the index of his inward character: everything about him denoted energy, earnestness and the best intentions. His legs, perhaps, were shorter than they should have been." (The Strachey touch is to be admired in the pseudo-diffident "perhaps" and "should." It added something to the joke that Strachey was a tall, dramatically ungainly man, built along the lines of a daddy longlegs.)

Other writers—Dickens, Wilde, Shaw, for example—assaulted the Victorian edifice without inflicting much permanent damage. But Strachey was an exquisitely destructive cartoonist, and his timing was as nice as his instinct for detail. Eminent Victorians appeared in the spring of 1918. After four years of the Great War and the slaughter of much of a generation of Europe's young men, hitherto imposing figures of the preceding age (Strachey's other subjects were Florence Nightingale, Gen. Charles "Chinese" Gordon and Cardinal Manning) seemed threadbare, exhausted. So, indeed, did the British Empire. Strachey's book became one of the 20th century's classic pieces of literary demolition, deft and deliciously unfair, an enactment of the late columnist Murray Kempton's crack about those who come down out of the hills after the battle is over to shoot the wounded.

The transition from one age to another brings a change in the lenses through which people view the history that is just past and their own place in the history that is now unfolding. The universe of those in power is mocked by those who are not in power—at least not yet—as, say, the television satirists Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert mocked the administration of George W. Bush.

But the power changes hands. What then? What lens does the mind use in the new dispensation?

I think of such questions as the 21st century tries to sort itself out—economically, politically, environmentally—and to organize its perspectives as it hastens into a new age. We need to have a context to imagine ourselves. What is our narrative line?

Ecclesiastes says there is "a time to break down and a time to build up": the oldest dynamic. King Lear, the "old majesty," goes mad and expires. Goneril and Regan are consumed. Somewhere beyond the curtain of the fifth act lies a world more stable and sane, less petty and less murderous and less ignoble.

A pedestrian subtheme is always at work at the same time. As Emerson said, "Every hero becomes a bore at last."

Napoleon acted out this bathos. On St. Helena, his young aide-de-camp, Gen. Gaspard Gourgaud, kept a journal:

October 21 [1815]: I walk with the Emperor in the garden, and we discuss women. He maintains that a young man should not run after them....

November 5: The Grand Marshal [Montholon] is angry because the Emperor told him he was nothing but a ninny....

January 14 [1817]: Dinner, with trivial conversation on the superiority of stout over thin women....

January 15: [He] looks up the names of the ladies of his court. He is moved. ‘Ah! It was a fine empire. I had 83 million human beings under my government—more than half the population of Europe.' To hide his emotion, the Emperor sings.

A disillusioning close-up—the debunker's friend—may excite hilarity at the expense of greatness. Poor Napoleon: in the 1970 film Waterloo, Rod Steiger played the emperor, giving an over-the-top performance in Steiger's smoldering sanpaku Actors Studio style. In the heat of the battle of Waterloo, Steiger's Napoleon, exasperated at Marshal Ney, yells: "Can't I leave the battlefield for a minute?!"

In its prospering days before television, Henry Luce's Time magazine had an assortment of lenses for heroes and bores, and a prose style that could turn into a resonant travesty of the Homeric. Often the cover-story formula—ritualized by the magazine's less imaginative editors—called for a paragraph devoted to what the cover subject had for breakfast. A 1936 story on Republican presidential candidate Alf Landon of Kansas, for example, stated: "At 7:20 he was down to a breakfast of orange juice, fruit, scrambled eggs and kidneys, toast and coffee...husky, broad-shouldered Governor Landon...a wide smile crinkling his plain, friendly face. ‘Top o' the mornin' to you all.'" Such close-up details (called "biopers," for "biography and personality," in queries that the editors in New York sent to correspondents in the field) were meant to give the reader some unexpected sense of what the person was like—and, equally important, to impress the reader with the magazine's intimate access to the powerful.

The Breakfast Technique had antecedents—from Plutarch and Suetonius up through Elbert Hubbard, the turn-of-the-20th-century writer and propagandist for can-do American inventors and tycoons, famous as the author of A Message to Garcia. Theodore H. White, who was Luce's Chungking correspondent during World War II and, much later, the author of the Making of the President books, used the closeup-and-breakfast technique in his sketches of candidates and presidents; White went in for the organ tones of Big History. But by 1972 he had grown a little ashamed of the Inside Glimpse. He remembered how reporters, himself among them, swarmed in and out of George McGovern's hotel room after McGovern received the Democratic presidential nomination. "All of us are observing him, taking notes like mad, getting all the little details. Which I think I invented as a method of reporting and which I now sincerely regret," White would tell Timothy Crouse for Crouse's book The Boys on the Bus. "Who gives a f— if the guy had milk and Total for breakfast?"

Emerson's dictum about heroes becoming bores applies not just to people but to literary styles, hemlines, to almost all trends and novelties, even to big ideas. Marxism and Communism, heroic and hopeful to many in the West after the October Revolution, became something more sinister than a bore—the Stalinist horror. Almost concurrently, during the 1920s, prospering American business seemed a hero to many ("The business of America is business," Calvin Coolidge famously said), but came to seem to many a villainous fraud and betrayer after the Crash of 1929. Herbert Hoover did not get far with his line, in November of 1929, that "any lack of confidence in the economic future or the basic strength of business in the United States is foolish." Franklin Roosevelt in the mid-'30s excoriated "economic royalists" or "Bourbons"—and then joked that his critics thought he "dined on a breakfast of grilled millionaire." ("I am an exceedingly mild-mannered person," he added, "a devotee of scrambled eggs.")

Then came yet another flip, a new lens. After Pearl Harbor, newly and urgently mobilized American business and industry became heroes again, churning out the immense quantities of guns, bombs, planes, ships, tanks and other materiel that were, in the end, a chief reason the Allies won World War II. It was in that context that General Motors President Charles Wilson, who became Eisenhower's secretary of defense, declared in 1953, "For years I thought that what was good for the country was good for General Motors, and vice versa." The statement would be uprooted from its postwar context and satirized as neo-Babbittry, a motto of the consumerist/corporate Age of Eisenhower.

The 1960s, which seemed chaotically heroic to many—an invigorating idealistic generational turning that followed the '50s, when the young were silent and the elders-in-power were senescent—came to seem, by the time of the Reagan administration and fitfully thereafter, oppressive, a collective demographic narcissism that had used up too much of the American oxygen for far too long.

Each age ingests the previous one at the same time it rejects it. The new age builds upon the old. The work is not discontinuous, and the currents of transmission are complex.

Duff Cooper read Eminent Victorians in the trenches in France, while serving as a lieutenant of the Grenadier Guards. He rather liked the book, but at the same time found it a little too gorgeously easy.

"You can't write well about a man unless you have some sympathy or affection for him," Cooper, the future diplomat, author and First Lord of the Admiralty, wrote to his wife-to-be, Lady Diana Manners. And Strachey, he wrote, seemed "to make no effort to understand [the Victorians] or to represent what they felt and what was their point of view, but simply to show how very funny their religious worries appear seen from a detached and irreligious standpoint....You feel rather that he is out to sneer, that he is like an agile, quick-witted guttersnipe watching a Jubilee procession."

One age's iconoclast is another's guttersnipe. Colbert and Stewart savagely mocked the administration of George W. Bush as they pioneered an evolving form of subversive pseudo-journalism. Now that the George W. Bush context has vanished into the past and the power belongs to Barack Obama—presumably a more congenial figure to Colbert and Stewart—where do they take their Strachey-esque talent for demolition? They, too, are sorting through lenses to find the appropriate new optic. Contrary to Duff Cooper, it may be hard for them to be funny about a man for whom they have too much sympathy. When mockery dissolves into piety, the viewer's mind wanders, or heads for the door.

What seems different now is that global technologies intensify a historical Doppler effect—the pace of events seems to increase as we move into the future. We are accustomed to thinking of history as a sequence—the Victorian Age, for example, flowing briefly into the Edwardian, and then tumbling into the rapids of the Modern, the periods segmented and distinctive.

But in the early 21st century, an intensely globalized world grows intolerant of sequence. Its dilemmas become urgent and concurrent, and seem to Doppler up to the highest pitch. Hegelian thesis and antithesis talk over one another. Political call and response become simultaneous, which implies an end of dialogue. Think of the global financial crisis as coronary fibrillation: the electrical circuits of the world's financial heart, the intricately sequenced atria and ventricles of exchange, lose their rhythm; the heart goes haywire, it stops pumping.

Millions thought for a few days in October 1962, during the Cuban missile crisis, that the world might end. In the First Congregational Church in Washington, D.C., the radical journalist I. F. Stone told an audience of peace activists: "Six thousand years of human history is about to come to an end. Do not expect to be alive tomorrow." Nikita Khrushchev was thinking along those lines when he said wistfully, "Everything alive wants to live." And yet there may sometimes be a sort of vanity in the "all changed, changed utterly" note that W. B. Yeats sounded after the rebellion of Easter 1916 in Ireland.

Big history cannot get any bigger than the End of the World, which is the most dramatic and, in its way, the least imaginative of narrative lines. In any case, apocalypse in human experience has proven to be a state of mind with urgent but shifting coordinates in reality: what it certainly means is that we have crossed a borderline and headed into strange country. We have been doing that from the start. But history itself—so far—has not been easy to kill.

Lance Morrow is writing a biography of Time magazine co-founder Henry Luce.