The TR-808 Drum Machine Changed the Sound of Pop Music Forever

Sometimes, technology has more impact after it’s obsolete

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/b4/90b4af91-468f-4b2e-8bf2-2d581afa3d84/808.jpg)

Even if you don't know the Roland TR-808 drum machine by name, you’ve almost certainly heard it. If you’re familiar with the percussion on Marvin Gaye’s 1982 hit “Sexual Healing”—those bursts of bass and snare drums amid robotic ticks and claps that collapse atop one another—then you understand how the machine can form a kind of bridge from one moment of breathless desire to the next. That’s the magic of the TR-808, which was released 40 years ago and played a major role in propelling “Sexual Healing” to the top of the charts. Less than a year after the song flooded American airwaves, the 808 was no longer in production, but it would not be forgotten for long: Appearing at the dawn of remix culture, the 808 and its successors soon helped turn the curation of machine-generated beats into its own art form.

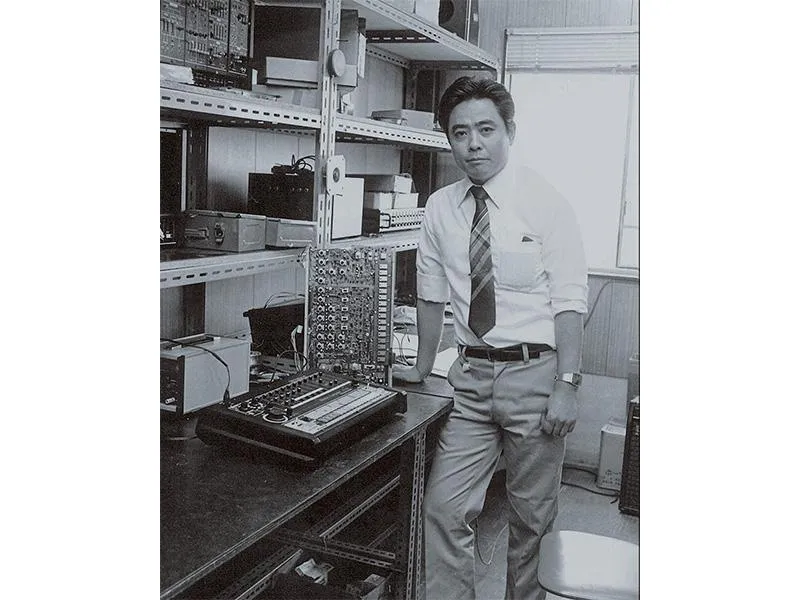

In the late 1970s, no one knew how to get realistic-sounding drums out of a machine, so a team of engineers at the Japanese company Roland, led by Tadao Kikumoto, began using analog synthesis—a process that manipulates electrical currents to generate sounds—to create and store sounds that mimicked hand-claps and bass notes and in-studio drums, creating catchy percussion patterns. Unlike most drum machines at the time, the 808 gave musicians remarkable freedom: You weren’t limited to pre-programmed rhythms or orchestrations, which meant you could fashion sounds and stack them on top of one another until you’d created something that had never been heard before. The TR-808 was in many ways a living and breathing studio unto itself.

During the two years that Roland kept the 808 in production, the machine created memorable moments. The influential Japanese synth-pop band Yellow Magic Orchestra played live shows with an 808 to enthusiastic audiences in Tokyo, and the producer Arthur Baker experimented with an 808 in a New York studio in the early 1980s and ended up producing the single “Planet Rock,” a hip-hop collaboration by Afrika Bambaataa and the Soul Sonic Force that reached No. 48 on the Billboard charts in 1982 and became one of the most influential records of the decade, helping inspire the first golden era of hip-hop.

But the 808’s initial heyday was short-lived and beset with naysaying: The machine was expensive. Critics complained that the malleable analog sounds didn’t sound like real drums—though they did sound enough like drums that an artist with an 808 could forgo hiring a drummer for a studio session, so musicians feared the 808 might put drummers out of business. Moreover, the semiconductors used in the 808 became difficult and finally impossible to stock. After about 12,000 units sold, Roland ceased production, and it seemed as though the era of the 808 had come to an abrupt and unceremonious end.

Ironically, it was the commercial failure of the 808 that would fuel its popularity: As established musicians began to unload their 808s at secondhand stores, the machine dipped below its initial $1,200 sticker price; by the mid-1980s, used 808s were selling for $100 or less, and the 808 became more accessible to young musicians, just as hip-hop and electronic dance music were preparing to make important leaps in their respective evolutions. Today, the 808’s legacy is most entrenched in Southern rap, where it is now nearly ubiquitous, thanks to the machine’s thundering bass, which comes alive in songs such as OutKast’s 2003 “The Way You Move.”

The 808 briefly sounded like the future, then briefly seemed to have no future. But it has provided beats for hundreds of hits, from Whitney Houston’s 1987 “I Wanna Dance With Somebody” to Drake’s 2018 “God’s Plan,” winning the affections of beatmakers across genres and generations, many of whom build their beats with 808s, or by remixing older 808-driven songs. If you want to get that classic 808 feel without buying the machine, just use the web-based software iO-808, released in 2016. With a few keystrokes, you can summon those analog 808 sounds that changed the world.

Status Cymbals

A selection of top answers to the centuries-old musical question, How do you get by without an actual drummer? —Ted Scheinman

Ismail al-Jazari's Mechanical Bands

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/56/54567fbb-4d5d-4cab-bdd5-d36143826da7/4.jpg)

The 12th-century Anatolian inventor, often considered the father of robotics, devised all manner of automatons, including elaborate clocks. He also created mechanical musical ensembles powered by water, with figurines of musicians: As water flowed through the mechanism, it exerted pressure on the valves of the flutist figurines to cre- ate melody, and on the wooden pegs of the drums and cymbals to regulate rhythm. These creations provided entertainment at royal parties.

Leon Theremin's Rhythmicon

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f7/cc/f7ccb38e-179e-40d4-afbe-a25d510fa869/1.jpg)

Russian inventor Leon Theremin worked with American composer Henry Cowell to create the first electronic drum machine in 1931. The Rhythmicon let a musician program beats using a keyboard that controlled a series of rotating wheels. Cowell debuted it in 1932 at the New School in Manhattan. One of the few ever built resides at the Smithsonian

Harry Chamberlin's Rhythmate

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f8/ca/f8cadd7d-7e36-4042-84d3-17fc2bdef161/5.jpg)

The inventor developed this machine, meant to accompany organs in family sing-alongs, in his California studio in 1949. The Rhythmate depended on a loop of magnetic tape that contained recordings of a drummer playing 14 different rhythms from which a user could select. Though Chamberlin built just a few, the Rhythmate’s tape-loop technology would prove integral to electric keyboards in the 1960s.

The Wurlitzer Sideman

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/5d/b45dffae-8f57-48f8-9743-44a25e645636/2.jpg)

Released in 1959, the Sideman gave users 12 electronic imitations of popular rhythms on a rotating disc, including tangos, fox trots and waltzes. The machine’s popularity drew criticism from the American Association of Musicians, who feared it would put percussionists out of business.

Linn LM-1 Drum Computer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/58/8f582d93-3800-4bf1-a0e2-f8e05c79eba7/3.jpg)

Designed by the American Roger Linn and introduced by his company in 1980, this was the first drum machine to include digitally recorded snippets of real drums. It drives John Mellencamp’s 1982 hit “Jack and Diane,” and Prince used an LM-1 on “When Doves Cry” in 1984.