Holding on to Gullah Culture

A Smithsonian curator visits a Georgia island to find stories of a shrinking community that has clung to its African traditions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/HoldingOn-curator-Georgia-tradition-631.jpg)

If a slave died while cutting rice stalks in the wet paddy fields on Sapelo Island, Georgia, those laboring with him were not permitted to attend to the body. The buzzards arrived first.

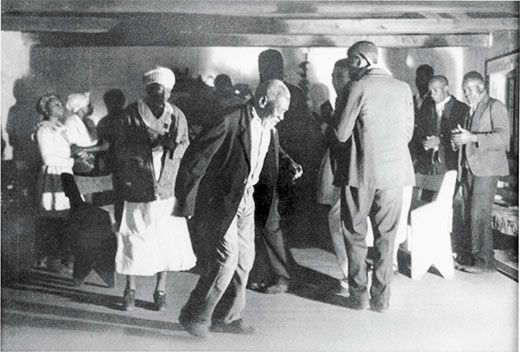

But at night, the deceased’s companions would gather to mourn. Dancing to the steady beat of a broom or stick, a circle of men would form around a leader—the “buzzard”— whose hands depicted the motion of the bird’s wings. He would rock closer and closer to the ground, nose first, to pick up a kerchief, symbolizing the body’s remains.

Cornelia Bailey, 65, is one of a handful of people still living on the 16,000-acre barrier island along Georgia’s Sea Coast. She remembers the “buzzard lope,” as the ritual was called. Growing up, she says, “you didn’t learn your history. You lived it.”

African-American linguist Lorenzo Dow Turner (1890-1972) was also privy to that history. In 1933, he conducted a series of interviews with Sea Coast residents—recorded on a bulky device powered by the truck engine of Bailey’s father-in-law. Thus he introduced the world to a community, known as Gullah or Geechee, that still retains music and dances from West Africa. Turner also studied the islanders’ unique dialect, which outsiders had long dismissed as poor English. But Turner’s research, published in 1949, demonstrated that the dialect was complex, comprising about 3,800 words and derived from 31 African languages.

Turner’s pioneering work, which academics credit for introducing African-American studies to U.S. curricula, is the subject of “Word, Shout, Song: Lorenzo Dow Turner Connecting Communities Through Language” at Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum through July 24. Exhibit curator Alcione Amos says the Washington, D.C. museum acquired many of Turner’s original notes, pictures and recordings from his widow, Lois Turner Williams, in 2003. But Amos knew if she wanted to supplement Turner’s work, she would have to act quickly.

Today, only 55 Sapelo natives, ages 3 to 89, live in the island’s lone village, Hogg Hummock. “I wake up in the morning and count heads, to make sure nobody died overnight,” Bailey says.

“I knew there wasn’t much more time before the people who recognize the people in these photographs, and remember the culture they represented, are gone, too,” Amos says.

So she retraced Turner’s steps, traveling across the island conducting interviews. Sitting in Bailey’s kitchen, Amos played recordings on a laptop. A man’s voice sounds faded and cracked beneath the steady hum of the truck generator.

“That’s Uncle Shad, all right,” Bailey says, straining to hear his words. “Sure is.”

Bailey and Nettye Evans, 72, a childhood friend, identified four pictures in Amos’ collection. “I think that might be your husband’s great-grandmother, Katie Brown,” Evans says, pointing to a picture of a proud-looking woman wearing mostly white.

Bailey drove Amos around the island in a boxy utility van, pointing out houses and fields and slipping into island dialect: binya is a native islander, comya is a visitor.

In the back seat, Bailey’s grandson, 4-year-old Marcus, played with plastic toy trucks. He doesn’t use those words. And while he knows some traditional songs and dances, Marcus will likely follow the path of Sapelo’s three most recent graduates, who attended high school on the mainland and went on to college, with no plans to return. “My daughters would love to live here. Their heart is in Sapelo,” says Ben Hall, 75, whose father owned the island’s general store until it closed decades ago from lack of business. “But they can’t. There’s nothing for them.”

The Sapelo Island Culture and Revitalization Society is working to build a Geechee Gullah Cultural Interpretative Village—an interactive tourist attraction recreating different time periods of island life. It would bring jobs and generate revenue, Bailey says. The society, however, needs $1.6 million to move forward with the project.

Meanwhile, at the museum, Uncle Shad’s voice, now identified, relates the island’s history. The culture is too strong to ever die out completely, Bailey says. “You’ve got to have hope there’ll always be somebody here.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)