Home is Where the Kitchen Is

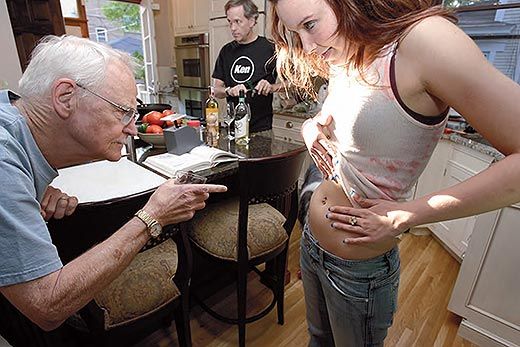

Photographer Dona Schwartz viewed her family through her camera lens in the hub of their household: the kitchen

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Dona-Schwartz-In-the-Kitchen-Breakfast-631.jpg)

For her latest book, photographer Dona Schwartz chose the home’s busiest shared space to observe how a newly blended family—two adults, one preteen, three teenagers, two college kids and two dogs—learned to live together. She spoke with Smithsonian’s food blogger, Amanda Bensen, about what she saw In the Kitchen.

Why do you think the kitchen is such a central point in a family’s life?

The key factor is that everybody eats, so it’s someplace where everybody’s going to turn up eventually. I guess there’s also the bathroom, but that would be even more unwelcome! (Laughs.) And there is something magnetic about the kitchen. There were often other places in the house we could have gathered that were larger or more comfortable—I mean, we have a living room—but for some reason we didn’t. The kitchen just seemed the default place to be.

How did this photographic project begin? Did you start it intentionally or discover a theme more accidentally?

It started about eight years ago, in 2002. I had been exiled from the kitchen on my birthday and I wasn’t very comfortable. Everybody thought they were doing me a great favor because I was always doing all the work as a single parent, but I was feeling like, Now what? Everyone’s in there and I’m out here. So I decided to pick up my camera and take photos. It was one of those “aha!” things when I realized that if you want to understand family, it makes a lot of sense to photograph where they congregate—in the kitchen. The seed was planted that night.

Did the concept or focus of your project change over time?

Well, the family changed when I moved in with my boyfriend. I was happily going along for about nine months doing the project in my own kitchen, and then I sold my house. I thought, What’s going to happen? Is it a mistake to move in with the person I love, because now the project’s going to end? And then it hit me that it didn’t have to end; it was just going to change. The whole question of blending became very pertinent.

Then the book came to revolve around not just the conventional nuclear family, but also the questions: What constitutes family? Can you make a conscious effort to create family when it does not exist in traditional terms? Can we knit together these separate trajectories—and then where do we go?

Also, I began to look for the moments when parents really make a mark on their children. That was particularly salient to me after my mother passed away in 2004. I started to feel that I had become my mother, and I wondered, When did that happen? There are these traits and idiosyncrasies that parents imprint on their children, that carry over into the next generation—and I knew it was happening, but I wanted to find out if I could see it happening.

Were the kids often cooking when you saw them in the kitchen? Did they cook meals for the family or just themselves?

They were usually just hanging out. Family meals? No. (Laughs.) For one thing, that’s hard to time. Even their idea of “morning” was variable. There’s a photo of one of the girls cooking breakfast, looking half asleep, and it’s 11 o’clock in the morning! Also, they each had their own things that they would and would not eat—with more on the “not” side of the list—and limited cooking skills. For example, my son is a vegetarian, but he eats a lot of packaged foods. To him, cooking meant making the trek from the freezer to the microwave.

So, most of the heavy-duty cooking was done by the adults. We’d usually give the kids some jobs, setting the table or helping with cleanup. We tried to be gentle about making them do things, because we knew they thought it was a pretty preposterous idea that just living in the same house suddenly made us a family.

Were certain foods more successful than others in terms of fostering interaction?

We tried to do things that, despite that diverse range in their diets, would work for everyone. Really, only two things worked. One was pizza night. We made our own dough and everything; it gave people things to do and talk about, it became a ritual. The other success was fajitas. People could put those together in ways that they liked and take ownership of them.

Do you think your family’s awareness of the camera influenced their behavior?

That’s hard to say. Because they did all know me as a photographer—they’d had exposure to that persona, so it was not unexpected. But I suppose at a certain point, they probably thought: Isn’t she done yet?

Any one picture you’d especially like to talk about?

Oh, thumbing through – some of them are so funny, they just kill me! There’s this one where (p. 83) Lara and Chelsea are frying an egg. They’re standing there watching this egg as if something miraculous is going to happen, and to me it was funny that it was such a weighty situation to them. It turned out to be the first time that either one of them had fried an egg! That was astounding to me. I was just sort of amazed at their amazement. And I like the two little flowers on the left side of the image, because the girls are sort of flowering into their own, and of course the egg has symbolic importance too.

When, and why, did this project come to an end?

I stopped photographing on a regular basis in the end of 2005, because there were only two kids left at home and the story really had in a way resolved itself. Things had settled in after two years; everyone kind of knew what to expect from everyone else, and the process of becoming a family had pretty much taken place.

How did the kids like the results?

You know, kids are so hard to figure out, so I really don’t know. Most of them were pretty nonchalant and haven’t spoken to me about it much. It’s been like: Oh, here’s Mom’s book. Oh hey, what’s for dinner?

What do you hope the public will learn from your work?

I think it’s really important that photographers, at least some of us, pay attention to the complexities of everyday life at this particular historical moment. Things change; families change; culture changes. Our way of living, at this moment in time, will vanish. Not everyone appreciates the importance of photographing these quotidian things but I think we need to preserve them, so that we know who we are.

Although there’s always an appetite for pictures of things that we’ve never seen before, we often overlook the things that are in our everyday lives that are actually quite complicated and interesting; even profound. Human beings are really complicated. You don’t have to travel anywhere to be able to make pictures of things that are really important to think about.

Dona Schwartz teaches photography and visual communication at the University of Minnesota’s School of Journalism and Mass Communication. In the Kitchen was published by Kehrer Verlag.