How Beatrix Potter Invented Character Merchandising

Faced with rejection, the author found her own path to fame and fortune

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2a/8a/2a8abb3f-22ac-4515-a9e1-93f61695a5b5/ed5yjh-wr.jpg)

Beatrix Potter is known for her gentle children's books and beautiful illustrations. But the sweet stories of Peter Rabbit, Jemima Puddle-Duck and others helped hide a savvy mind for business—and an author who was among the first to realize that her readers could help build a business empire.

Since her first book was published in 1902, Potter has been recognized as an author, artist, scientist and conservationist. But she was also an entrepreneur and a pioneer in licensing and merchandising literary characters. Potter built a retail empire out of her “bunny book” that is worth $500 million today. In the process, she created a system that continues to benefit all licensed characters, from Mickey Mouse to Harry Potter.

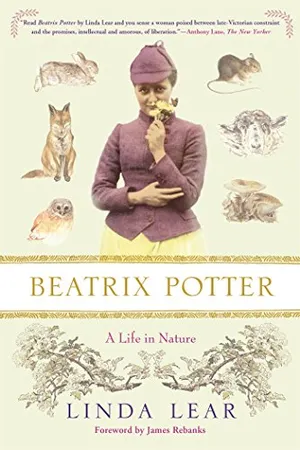

“She was an incredibly astute businesswoman,” says Linda Lear, author of Beatrix Potter: A Life In Nature. “It’s not generally known how successful she was at it. My view is that she was a natural marketer. She came from a marketing family and mercantilism was in her blood.”

Potter’s paternal grandfather, Edmund Potter, ran the largest calico printing company in England and was the co-founder of the Manchester School of Design. As such, Potter grew up wealthy, providing her the luxury to spend much of her childhood drawing, painting and studying nature on the family estates. There, she collected a menagerie of pets that included snakes, salamanders, bats, birds, snails, hedgehogs and two rabbits named Peter and Benjamin Bouncer.

In 1893, when she was 27 years old, Potter wrote a charming letter about Peter Rabbit to Noel Eastwood, the son of her former governess, Annie Moore. It was one of several letters Potter wrote to Moore’s children over the years. They were so well-loved that Moore suggested they might make good children’s books. So Potter borrowed the letters back and set about expanding Peter Rabbit by adding text and illustrations. She sent the book off to publishers—who promptly rejected it.

Part of the problem was that the publishers didn’t share Potter’s vision for her book. They wanted rhyming poetry—Potter’s text was plainspoken. They wanted a big book—Potter wanted small. They wanted the book to be expensive—Potter wanted to keep the price around one shilling, writing that “little rabbits cannot afford to spend 6 shillings on one book, and would never buy it.”

These ideas weren’t whims, but were based on Potter’s assessment of the book market. Her manuscript was modeled after The Story of Little Black Sambo by Helen Bannerman, a bestseller at the time. Potter made her book small like Sambo—not just because she believed it would better fit little hands, but also because it was on trend. “After a time there began to be a vogue for small books,” she wrote in 1929, “and I thought Peter might do as well as some that were being published.”

Since no publisher was willing to listen to her ideas, Potter chose to self-publish The Tale of Peter Rabbit. In September 1901, she ordered 250 copies for 11 pounds. A few months later, she ordered a second printing of 200 copies. In between, the publisher Frederick Warne & Co.—which had previously rejected her—began negotiations to publish the color edition. By self-publishing, “she was then able to show the Warne brothers [Norman, Harold, and Fruing] that the book was a success. That persuaded them to take on the book themselves,” says Rowena Godfrey, chairperson of the Beatrix Potter Society.

Warne’s first print run of The Tale of Peter Rabbit sold out before it was even published in October 1902 . By the end of the year, 28,000 copies had been sold. It was in its fifth printing by the middle of 1903. “The public must be fond of rabbits!” Potter wrote to Norman Warne. “What an appalling quantity of Peter.”

Despite the popularity of Peter, Warne somehow neglected to register the American copyright for the book. That left Potter helpless against publishers who printed unauthorized copies of her books in the United States. (Not only was her work pirated, but Peter Rabbit often showed up other books, such as Peter Rabbit and Jimmy Chipmunk or Peter Rabbit and His Ma.) It was a problem that plagued Potter for years. From then on, she was careful to protect her legal rights.

“She learned a lesson from the fact that Peter Rabbit was never patented in the United States, which is horrifying,” says Lear. “It was a huge loss of revenue for her. So she didn’t trust Warne, and decided to go ahead and do things herself.”

The first thing she did was to sew a Peter Rabbit doll as a prototype to manufacture. She seemed to have fun making the doll, writing to Warne: “I have not got it right yet, but the expression is going to be lovely; especially the whiskers—(pulled out of a brush!)”

Again, Potter was responding to market trends. She’d observed that Harrods, the iconic British department store, was selling dolls based on an advertising character, Sunny Jim, noting that “there is a run on toys copied from pictures.” Her father also saw a squirrel doll named “Nutkin” for sale in a shop shortly after The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin was published. It was clear that if she didn’t make a doll based on her characters, someone else would.

In December 1903, Potter patented the Peter Rabbit doll. Now, if someone tried to make a Peter Rabbit doll without her permission, she would have legal recourse. This was an unusual move for the time, and one of the earliest patents on a literary character.

Potter enthusiastically oversaw the manufacturing of the Peter Rabbit doll, investigating potential fabricators and patriotically insisting it be made in England. She also invented other merchandise, which she called her “sideshows.” Her next project was a board game in which Mr. McGregor chases Peter Rabbit around a maze of squares. She even enlisted Norman Warne to carve the game pieces. “I think this is a rather good game,” she wrote to him. “I have written the rules at some length, (to prevent arguments!)”

The game was patented, but Warne didn’t put it out for many years. In fact, Potter's stodgy Victorian publishers were slow to understand what their bestselling author was doing. They were concerned that the commercialism would seem vulgar.

“This kind of thing wasn’t done,” says Lear. “Warne was an establishment publisher, and they didn’t want to go out on a limb and do something that the public would think was in bad taste. It wasn’t until she started patenting things herself that they thought, uh oh, and went ahead and did it. And lo and behold, it sold like gangbusters.”

In each case, Potter monitored her sideshows to the last detail. She designed and painted figurines and sewed a Jemima Puddle-Duck doll. She oversaw the contract for manufacturing tea sets. She made wallpaper, slippers, china, handkerchiefs, bookcases, stationery, almanacs, painting books, and more. Soon, her line of merchandise was as profitable as the books themselves.

“She was a perfectionist, and I believe that this is what made all her work so appealing and enduring,” says Godfrey. “Her ideals have been followed ever since, and the quality of Potter merchandise is usually of a phenomenal standard.”

Later, the “sideshows” helped save her publishers. In 1917, Harold Warne was arrested for embezzlement and Warne & Co. was in danger of financial collapse. By then, Potter had shifted her interest to sheep farming and conservationism, but to help her publishers, she put out another book— Appley Dapply’s Nursery Rhymes—along with many new products. Today, Warne & Co. is owned by Penguin Random House, which controls the Beatrix Potter brand. The Tale of Peter Rabbit has sold more than 45 million copies worldwide in 35 languages.

Of course, Potter wasn’t the only writer to merchandise her work. As early as 1744, there were dolls based on the books of John Newbery, the “father of children’s literature” and the namesake for the award. In Canada, Palmer Cox’s popular Brownies were used on a variety of advertising products and merchandise. Even Potter’s contemporaries, like The Wizard of Oz author L. Frank Baum, were busy commercializing their books with stage plays and souvenirs.

What makes Potter’s approach unique, however, is the amount of merchandise she sold and the patents she was able to secure. She combined legal protection with marketing instincts and creative vision to make a successful product line. In modern terms, she created a brand out of her artistic work—an approach that has been imitated ever since.

Those endeavors were successful because Potter never forgot her customer—the children who loved her books.

“She saw that books could be an unlimited market, even little books that children could hold,” says Lear. “For if they fell in love with Peter, and they wanted more, why not?”