How the Creators of Loving Vincent Brought the First Fully Painted Animated Film to Life

Vincent van Gogh’s swirling coats of paint really move in the Oscar-nominated film thanks to 62,450 original oil paintings

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/63/d963638c-22fd-4363-9282-c0f329ec016f/lovingv.jpg)

When Vincent van Gogh stumbled into the French village of Auvers-sur-Oise during the summer of 1890, he was bleeding from a bullet wound lodged in his upper abdomen, days away from dying in relative obscurity.

Found on his person was not a suicide note, but rather what is believed to be a rough draft of a letter the 37-year-old artist had just mailed to his brother, Theo.

Throughout his life, Vincent had drafted hundreds of letters to his brother. His last missive to him was remarkable only for how ordinary it was, as was this unsent draft, which contained several lines omitted from the final letter. In one of those forgotten lines Vincent writes, sounding almost resigned, “Well, the truth is, we cannot speak other than by our paintings.”

That sentiment has long stayed with Dorota Kobiela. A classically trained artist, she first came across the draft of his last letter while researching Vincent’s life at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw for her thesis on artists and depression. After graduation, she found herself unable to get his words out of her head, and began working on a hand-painted seven-minute animated short to excise the artist from her mind.

“It was a vision of his last days,” she says. “What he would do. Get up, put his shoes on, pack his paint box. Maybe pack the revolver?”

But the trajectory of the film changed when, as she waited on public grant money to come through to start production, she connected with U.K. producer and filmmaker Hugh Welchman, who persuaded her that the idea deserved a feature treatment.

Kobiela agreed, and they spent the better part of the last decade crafting what they call an “interview with his paintings.” The exhaustive process (bolstered financially by a viral Kickstarter campaign and grant money from the Polish Film Institute) has created something unique: Loving Vincent, the first fully painted animated movie. The film, recently nominated for an Academy Award in the Animated Feature Film category, uses 62,450 original oil paintings to give voice to Vincent’s final days.

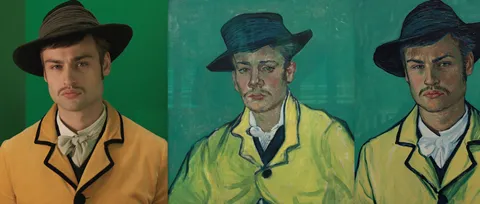

Loving Vincent, which is framed like a film noir murder mystery, is told through the perspective of the young man wearing an ill-fitting yellow coat and a suspicious expression in Vincent’s “Portrait of Armand Roulin (1888).”

“We always loved the painting,” says Welchman. “He’s very, in a sense, good looking, you know, this powerful teenager. He’s a bit suspicious of the person who’s painting him. You get this testy testosterone kind of feeling about him and sort of a pride.”

Armand, the son of the village postmaster, is tasked to deliver Vincent’s last letter to Theo. As the brooding teen tries to track Theo down, he retraces Vincent’s steps in Auvers and encounters the last people to know the artist. Through conversations with them, he begins to question the circumstances that led to Vincent’s death. Was it suicide? Or was it murder?

Loving Vincent was first shot with actors on a green screen and then a team of more than 100 artists transposed the film into moving art using paint-on-glass animation. The laborious technique, first pioneered by Canadian-American filmmaker and animator Caroline Leaf in the 1970s, has been used before, notably in Russian animator Aleksandr Petrov’s shorts. But this is the first feature-length film done in the style. That’s likely because the method—striking for how it allows images to subtly morph and evolve on screen— requires artists to paint over each frame of the film on glass.

“This is the first time that anyone has had the initiative and, really, drive and ambition to be able to achieve an entire [painted animation] feature film,” says Andrew Utterson, film historian and associate professor of screen studies at Ithaca College.

As Utterson points out, it’s not just the film’s scale that’s remarkable, but also its form. “We get a painted animation about a painted life,” he says. And if you dig in, that relationship goes even deeper. Vincent was infamous for pushing himself to the extremes for his work, and by choosing this technique, Utterson explains, the filmmakers put themselves through a similarly punishing process.

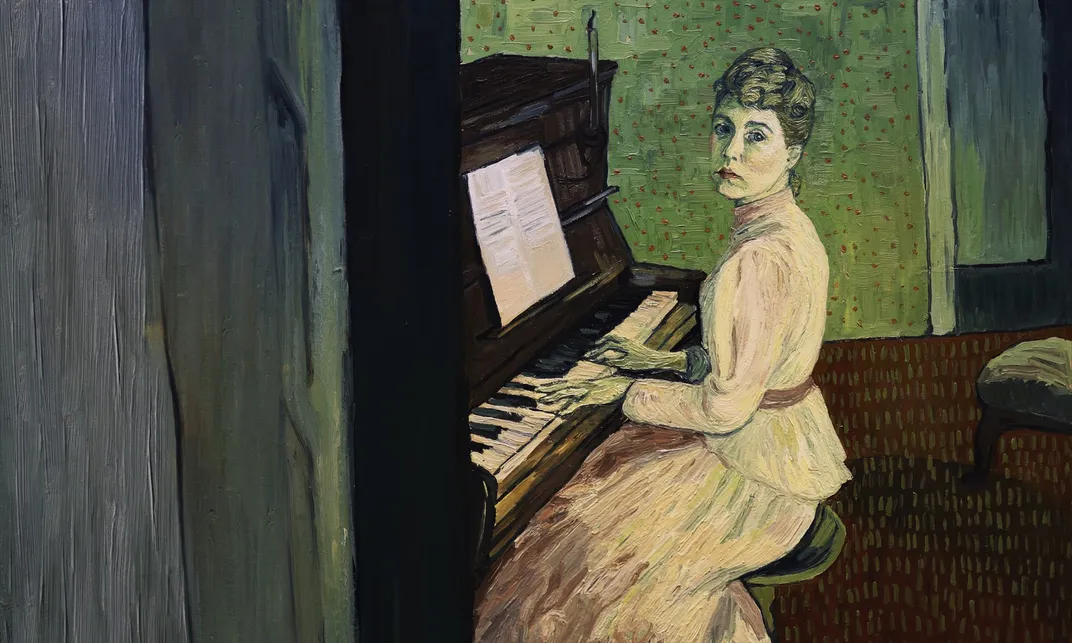

The payoff is in the final product. The individual frames of the film are a work of art in their own right. In each frame, the team of artists mimicked the thick layers of oil paint that Vincent mixed on his canvases with his palette knife and hands through a technique called impasto. To get the interpretations just so, the filmmakers consulted with the Van Gogh Museum to get the equipment, paint and colors Vincent used down to the exact shade.

It’s perhaps most interesting, though, when the filmmakers are forced to take some creative liberties to engineer Vincent’s art to suit the film’s needs. As Welchman explains: “Vincent’s iconic style is very overlit. It’s scorching sunshine, it’s burning, bright colors, and very hopeful.” In order to stay true to Vincent’s art and fit the story’s film noir color story (or as Welchman puts it, “take some of his daytime paintings into the nighttime”), the team pulled inspiration from the handful of paintings Vincent did make at night like “The Starry Night” and “Café Terrace at Night” to distill the rest of Vincent’s oeuvre with a moodier palate.

Film noir itself might not seem like the most obvious choice for a docu-drama on Vincent (who died almost half a decade before the term was even introduced). However, Kobiela and Welchman say they are fans of the 1940s hard-boiled aesthetic, and saw the genre as a way to give Loving Vincent a murder-mystery underpinning.

The central question in Loving Vincent is whether Vincent attempted to kill himself in the Auvers wheat fields or rather had been shot—on purpose or by accident—by one of the members of a pack of local boys who had taken to mocking Vincent as he worked. The theory that the boys had a hand in Vincent’s death was originally circulated in the 1930s after art historian John Rewald interviewed locals in Auvers and first heard rumors about young boys, a gun and the death of the artist.

The filmmakers say they were at a critical point in writing their script when Steven Naifeh and Gregory White published their 2011 biography, Van Gogh: The Life, which resurfaced the idea of the accidental shooting.

“It came at a very interesting moment for us,” Welchman says of the book. Like so many before them, they had been scratching their heads, wondering why Vincent had committed suicide just as he was starting to be recognized as an artist. Something wasn’t adding up.

“He just had his first amazing review,” says Welchman. “Monet, who was already selling his paintings for 1,500 francs—which was a lot of money in those days—said that Vincent was the most exciting new painter coming through. It seemed like success was inevitable, so why kill himself at that point, compared to some of the other moments in the previous nine years, which seemed to be much more brutal and desperate?”

Then again, Vincent wasn’t taking care of himself. During this time, he was putting his body under an incredible amount of strain: working long hours under the southern sun and subsisting on alcohol, coffee and cigarettes. While Theo sent money to him every month, Vincent often spent it all on prints or equipment for his paintings, often satisfying his hunger with just bread as he went about a punishing schedule full of painting, writing and reading. “He was just going at an incredible speed,” says Welchman, “if you do that for a long time it leads to a breakdown.”

Of course, Loving Vincent cannot solve the mystery around Vincent’s death or, for that matter, deliver a conclusive timeline for what happened during those final days in Auvers. But the story finds a new way into his final days through the moving art the film brings to life.

“For us, the most important thing was Vincent,” says Welchman. “His passion and his struggle was to communicate with people, and one of his problems was that he wasn’t really good at doing it face to face and that’s why his art communicates so beautifully.”

It’s a sentiment that’s at the very core of Loving Vincent. The movement and emotion in Vincent’s art has transcended time, culture and geography. To take his static frames and add motion to them feels almost unsettling in its novelty. Set to composer Clint Mansell’s emotive score, the result, equal parts 21st-century technology and late 19th-century art, is thrilling to behold.

And when the inevitable thick blue and green swirls of “Starry Night” come on the screen, alive in a different way than they’ve been shown before, it’s hard to deny the filmmakers have found something new here in Loving Vincent, unlocking a different way to frame art known the world over.