How E.B. White Wove Charlotte’s Web

A new book explores how the author of the beloved children’s book was inspired by his love for nature and animals

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/EB-White-Charlottes-Web-631.jpg)

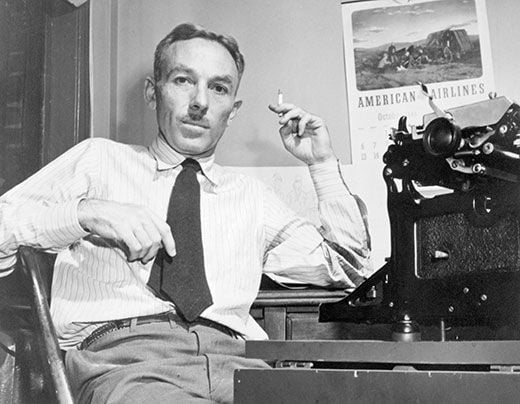

Not long before E.B. White started writing his classic children’s story Charlotte’s Web about a spider called Charlotte and a pig named Wilbur, he had a porcine encounter that seems to have deeply affected him. In a 1947 essay for the Atlantic Monthly, he describes several days and nights spent with an ailing pig—one he had originally intended to butcher. “[The pig’s] suffering soon became the embodiment of all earthly wretchedness,” White wrote. The animal died, but had he recovered it is very doubtful that White would have had the heart to carry out his intentions. “The loss we felt was not the loss of ham but the loss of pig,” he wrote in the essay.

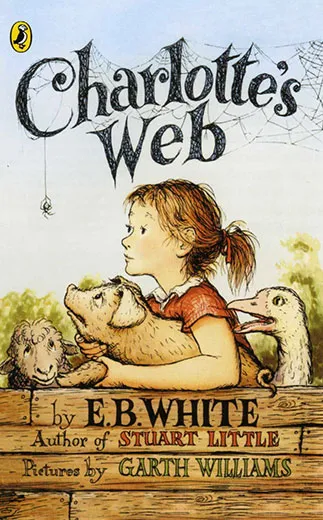

That sentiment became part of the inspiration for Charlotte’s Web, published in 1952 and still one of the most beloved books of all time. Now a new book by Michael Sims focuses on White’s lifelong connection to animals and nature. The Story of Charlotte’s Web: E.B. White’s Eccentric Life in Nature and the Birth of an American Classic explores White’s encounters with frogs and field mice, rivers and lakes, stars and centipedes, to paint a portrait of the writer as a devoted naturalist—the 20th-century heir to Thoreau, perhaps. White once wrote of himself, “This boy felt for animals a kinship he never felt for people.” Examining White’s regard for nature and animals, Sims unpacks the appeal of Charlotte’s Web.

Sims originally conceived of his book as a larger project, one that would examine how authors of children’s books, such as Beatrix Potter and A.A. Milne, had been inspired by nature, but he came to focus entirely on White, he recently told me, because White’s preoccupation with the natural world outweighed that of most other authors. “Certain writers have an empathy for the world,” Sims said. “Their basic writing mode is personification. E.B. White is that kind of writer; he could animate a splash of sunlight.”

The seeds of White’s fascination with nature were planted early, according to Sims’ account. The youngest of his seven siblings and painfully shy, Elwyn Brooks White was “miserable when more than two people at a time looked at him.” Of fragile health, he suffered from hay fever, in particular, which led one doctor to recommend that his parents “douse his head in cold water every morning before breakfast.” In search of fresh country air, his family would travel most summers to a rustic lakeside camp in Maine. Young Elwyn also scoured the nearby woods and barn of his boyhood home in Mount Vernon, New York, acquainting himself with farm animals and assorted critters. Gradually, Sims says, Elwyn “became aware that animals were actors themselves, living their own busy lives, not merely background characters in his own little drama.”

As an adult White found communion with only a few select humans, most of them at The New Yorker—his wife, Katharine Angell, an editor at the magazine; its founder, Harold Ross; and essayist and fiction writer James Thurber, another colleague. In fact, White’s preoccupation with nature and animals became a kind of shield in his adult life. “He hid behind animals,” Sims writes. During his college years, White tried to woo one of his Cornell classmates by comparing her eyes to those of the most beautiful creature he could summon: his dog, Mutt. Years later when Angell announced she was pregnant with their first child, he was struck speechless, so he wrote a letter to her “from” their pet dog Daisy, describing the excitement and anxiety of the dog’s owner. “He gets thinking that nothing that he writes or says ever quite expresses his feeling,” wrote “Daisy,” “and he worries about his inarticulateness just the same as he does about his bowels.” In one of his early New Yorker pieces, White interviews a sparrow about the pros and cons of urban living, an issue that would preoccupy the writer as well.

Columns for The New Yorker were White’s bread and butter, but he had already written one children’s book before Charlotte’s Web. Published in 1945, Stuart Little is the story of the adventures of a tiny boy who looked like a mouse. White, who once admitted to having “mice in the subconscious,” had been fascinated by the creatures for decades and had made them the subject of his childhood writings and stories for family gatherings.

Apparently, he was just as taken with spiders. Fifteen years before penning Charlotte’s Web, spiders informed one of White’s romantic tributes to Angell, a poem in which he describes a spider “dropping down from twig,” descending “down through space” and eventually building a ladder to the point where he started. The poem concludes:

Thus I, gone forth, as spiders do,

In spider’s web a truth discerning,

Attach one silken strand to you

For my returning.

In the fall of 1948, while doing chores in his barn in Brooklin, Maine, White began to observe a spider spinning an egg sac. When work called him back to the city, he was loathe to abandon his small friend and her project and so he severed the sac from its web, placed it in a candy box, and brought the makeshift incubation chamber back to the city, where it lived on his bedroom bureau. Several weeks later, the spiders hatched and covered White’s nail scissors and hairbrush with a fine web. “After the spiders left the bureau,” Sims writes, “they continued to scurry around in [White’s] imagination.”

Upon publication, Charlotte’s Web, a story of a clever spider who saves a pig, had obvious appeal to children, but adults heralded it as well. In her review for the New York Times, Eudora Welty wrote that it was “just about perfect, and just about magical in the way it is done.” Pamela Travers, the author of the Mary Poppins series, wrote that any adult “who can still dip into it—even with only so much as a toe—is certain at last of dying young even if he lives to ninety.”

White lived to the age of 86. Though admired for his essays, his fiction and his revision of William Strunk’s Elements of Style (still a widely used guide to writing), it is Charlotte’s Web that keeps his name before the public, generation after generation. Some 200,000 copies are sold every year, and it has been translated into more than 30 languages. The book repeatedly tops lists compiled by teachers and librarians as one of the best children’s books of all time.

Looking back on the success of Charlotte’s Web a decade after it was published, White wrote in the New York Times in 1961 that writing the book “started innocently enough, and I kept on because I found it was fun.” He then added: “All that I ever hope to say in books is that I love the world. I guess you can find that in there, if you dig around. Animals are part of my world and I try to report them faithfully and with respect.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)