How Ferris Bueller’s Day Off Perfectly Illustrates the Power of Art Museums

Three decades after it premiered, the coming-of-age film remains a classic

Thirty years ago, a high school senior forever changed the game of cutting class.

In 1986, the persistently optimistic Ferris Bueller of the fictional Shermer, Illinois, broke the fourth wall and invited filmgoers to join him in taking a break from the vapidity of high school because, as he says, “Life moves pretty fast. If you don't stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.”

From the genius mind of John Hughes, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off was an instant classic, grossing over $70 million in theaters and earning star Matthew Broderick a Golden Globe nomination for best actor. The film follows Ferris, his girlfriend Sloane and his best friend Cameron as they skip school in Chicago’s North Shore suburbs to explore the sites of the Windy City.

And while much of the appeal of the film lies in Ferris' breezy attitude, there’s more to this feel-good film than the absurdity of his shenanigans. Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, a masterpiece in itself, flawlessly captures art’s ability to influence our perception of ourselves and the world around us, especially when we’re least expecting it.

In the decades after the film’s release, fans have glommed onto their favorite moments, scrutinizing the scenes shot at Wrigley Field to identify which actual Cubs baseball game the trio attended. After much discussion and debate, a writer at Baseball Prospectus proved in 2011 that Ferris and his cohort attend the June 5, 1985, game between the Cubs and the Braves. And while this intense scene research is impressive, if not strangely obsessive, there’s (at least) one more scene in the film that deserves the same treatment.

Of all the wild antics Ferris and friends enact during their day off – stealing a car, dancing in a parade, faking an identity to gain access to a fancy restaurant – perhaps the most surprising, yet significant, is their stop at the Art Institute of Chicago. The scene, an ode to Hughes’ personal admiration for the museum, takes the film from feel-good teen flick to thought-provoking cinema, and establishes its place among the best museum movies of all time.

Set to The Dream Academy’s cover of The Smiths’ “Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want,” the scene filmed at the Art Institute of Chicago is undeniably odd, and not just because its three teenagers playing hooky by going to a museum. The style of the scene more closely resembles a music video than a feature film, with its unusual lengthy close-ups, lack of dialogue and dreamy background music. Yet, that scene is perhaps the pivotal moment in the development of Cameron, whose existential, bleak outlook on life clashes with Ferris’ eternal enthusiasm.

“It’s an important movie, but it’s one that ages well. I’ve seen any number of high school movies and they are painful now. You had to be in the moment in order for them to matter. This one aimed higher and it succeeded,” says Eleanor Harvey, senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

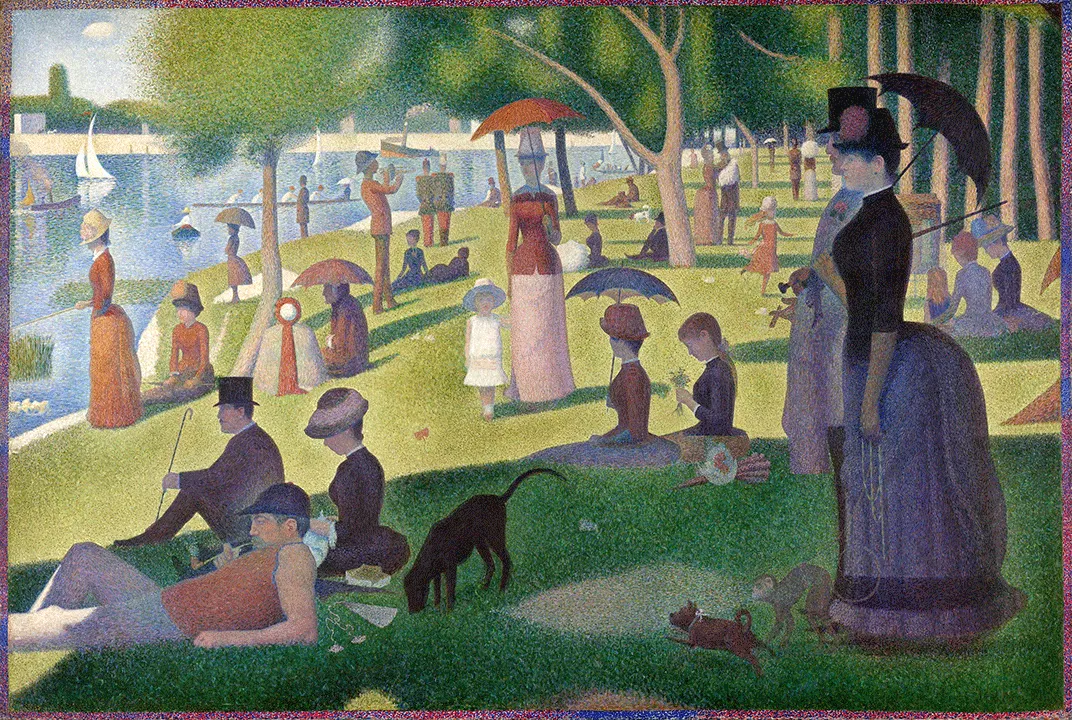

Unlike Ferris and Sloane, who remain happy and carefree throughout the film, Cameron is constantly wrestling his inner demons. He reluctantly follows Ferris’ lead, and at the museum, he plays along with Ferris and Sloane’s spoof of the art-going experience, mimicking the positioning of a Rodin statue and running through the gallery with a group of children. But once separated from his friends, Cameron finds himself in a moment of serious introspection in front of George Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte.

The camera cuts back and forth between Cameron’s face and the face of the young girl at the center of the pointillist painting. Inching closer to the canvas with each cut, the camera is eventually so close to her face that it is no longer identifiable as such.

“He’s struggling to find his place and he dives into the face of that little kid,” says Harvey. “It almost brings me to tears, because he’s having a soul-wrenching, life changing experience. When he comes out of that painting, he will not be the same.”

While Ferris and Sloane are, perhaps alarmingly, confident in who they are, Cameron is constantly searching for his raison d’être. Just as the little girl in the painting faces a different direction from everyone around her, Cameron is experiencing life differently from his peers and particularly his best friend. In this little girl, Cameron begins to understand himself.

“Cameron could not have anticipated that this would be anything but a fun goofball day and in a sense that painting becomes our first concrete clue that Cameron is deeper than everyone else in that movie,” says Harvey.

This sense of epiphany is one that Harvey encourages all museum visitors to engage. “I think that absorption of diving into a picture is as though you have seen yourself looking back at you and you have dived in so deeply you cease to exist,” she says about life changing art. “What I tell people when they go through art museums is…there will be a moment where you are dumbstruck in front of something and it changes your life forever.”

Hughes also alluded to this notion in an audio commentary featured on the film’s 1999 DVD release. “The closer he looks at the child, the less he sees with this style of painting. The more he looks at it there’s nothing there. He fears that the more you look at him there isn’t anything to see. There’s nothing there. That’s him.”

Says Harvey, "Cameron needs to realize going through life scared is the wrong way to do it. That encounter with the painting in some weird way gives him the courage to understand that he can stand up for himself."

“As a mom of two kids, one in high school, one in college, that’s the moment you wait for when your kid is no longer doing what everyone else wants to do, or passively receiving the education that they’re getting or passively learning how to execute the orders being given to everyone all around them, but they finally understand ‘Oh my god, it really is about me. I really do need to know what I care about, who I am and why that matters.’ So yeah, over 30 years that scene has come to mean more and more.”

Neither Ferris nor Sloane undergo much in the way of character development during the film, their private moment at the Art Institute is revealing in itself. As Harvey notes, Ferris and Sloane have differing ideas on the future of their relationship. As Ferris has clearly checked out of high school and is ready to move on, Sloane’s crush on him only intensifies during the film to the point of her telling Cameron, “He’s going to marry me.” When separated from Cameron, Ferris and Sloane find themselves in front of Marc Chagall’s “America Windows,” or what Harvey calls an “ecclesiastic stained glass in a kiss that could be in front of an altar,” supporting Sloane’s marriage fantasy.

The beauty of the quirky scene, set right before Ferris’ jubilant takeover of Chicago’s Von Steuben Day parade, is in its affirmation that art has the power to impact people in profound ways, and museums are critical in facilitating that.

“I think in a certain sense [the scene] mirrors the journey into an art museum or any unfamiliar territory. You start thinking it’s a lark and then you make fun of it and then you begin to realize that there’s power here and you either reject it or you dive in,” says Harvey.

So, the next time you’re at an art museum, remember Ferris’s sage advice about life moving pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around, you might just miss an opportunity to learn something about yourself.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)