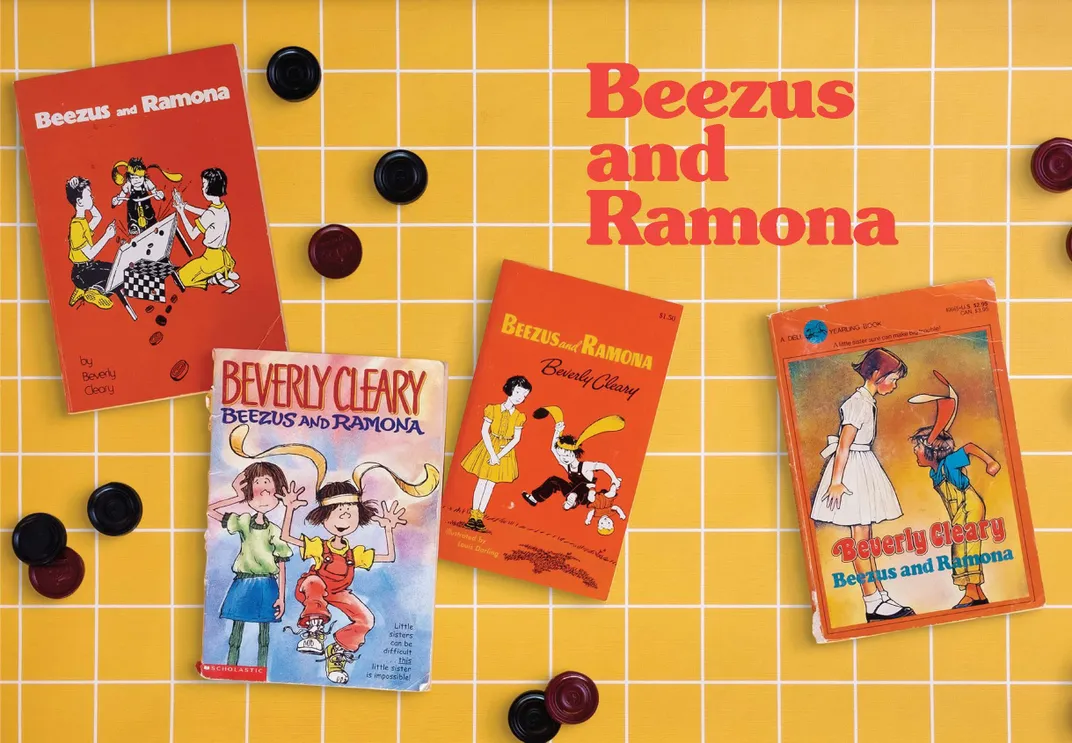

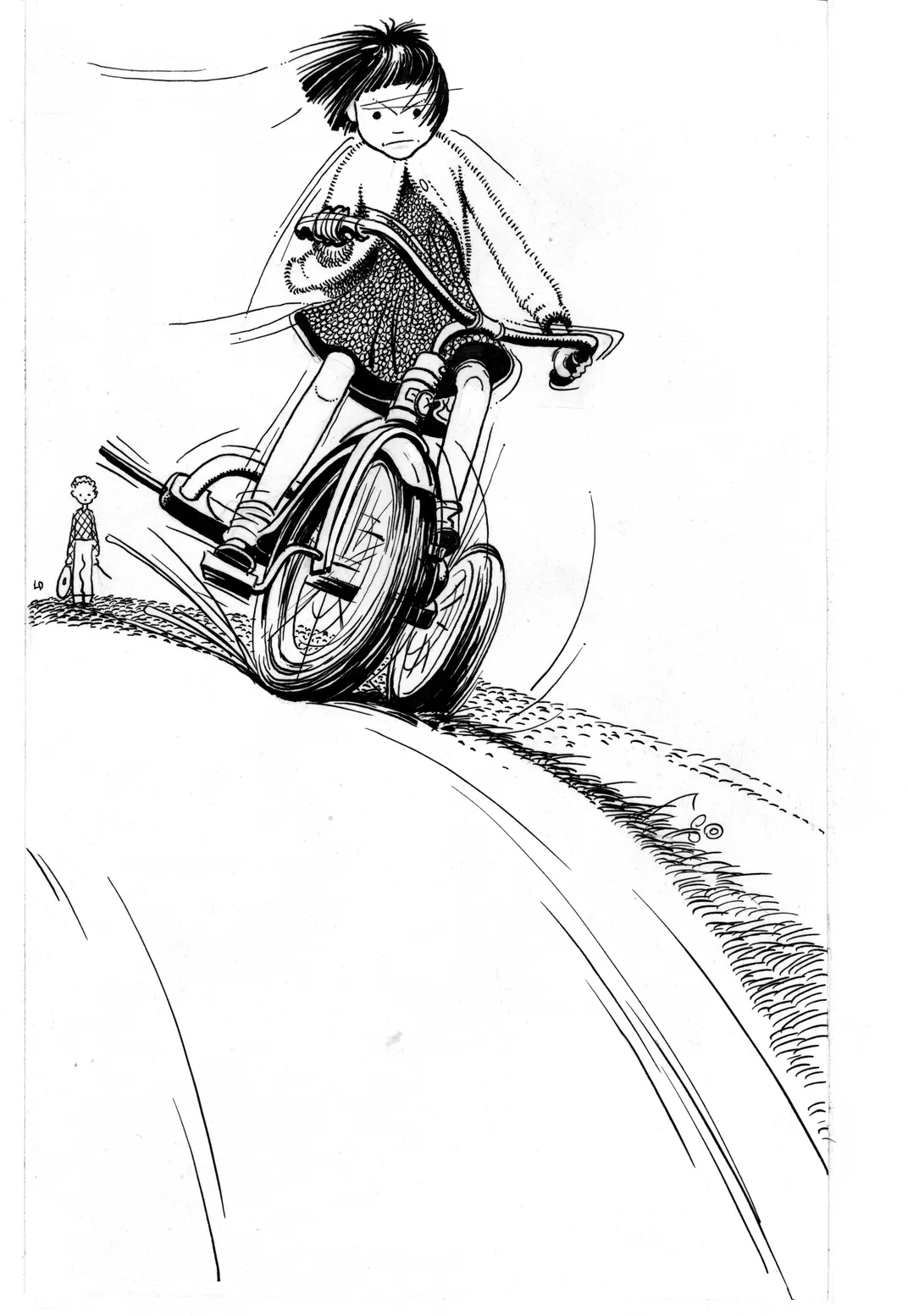

Based on purely anecdotal research, one might conclude that Ramona Quimby readers remember the illustrations with which they grew up as the illustrations. Baby boomers wax nostalgic about Louis Darling’s ink illustrations, with their elegant simplicity and retro styling. His illustrations are especially cherished because you can only find them in the first two books of the series, due to Darling’s early death in 1970, at the age of 53.

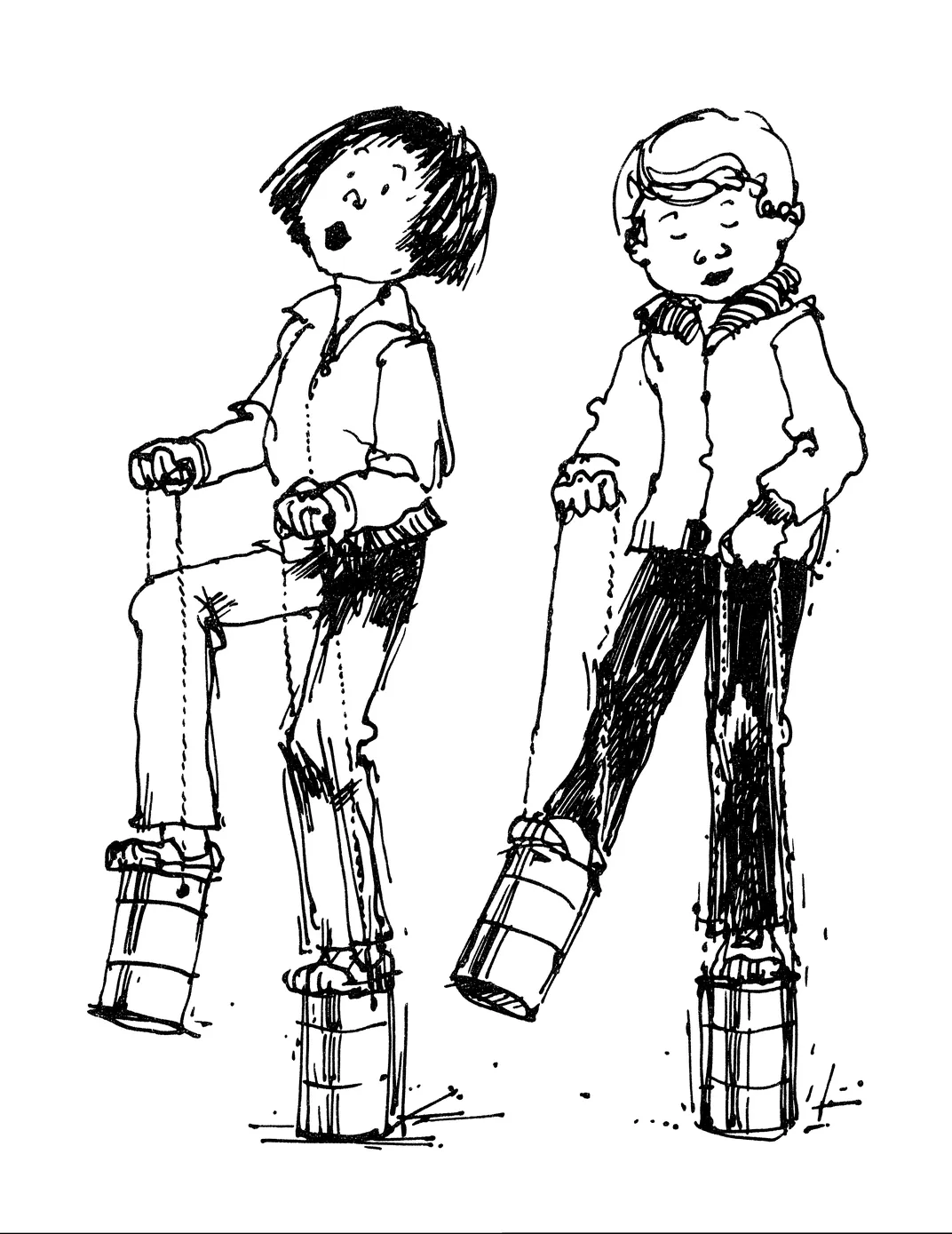

For children born in the 1970s through the 1990s, the late Gen Xers and vintage Millennials, Ramona and Beezus had pageboy haircuts, dots for eyes, and funny little mushroom noses. They wore decidedly seventies-style outfits, rendered in slashy and crosshatched ink lines. This was the work of Alan Tiegreen, who took over the series from the late Darling for the publication of the third book of the series in 1975. Tiegreen created cover art for the first seven books but only illustrated the interiors of the last six.

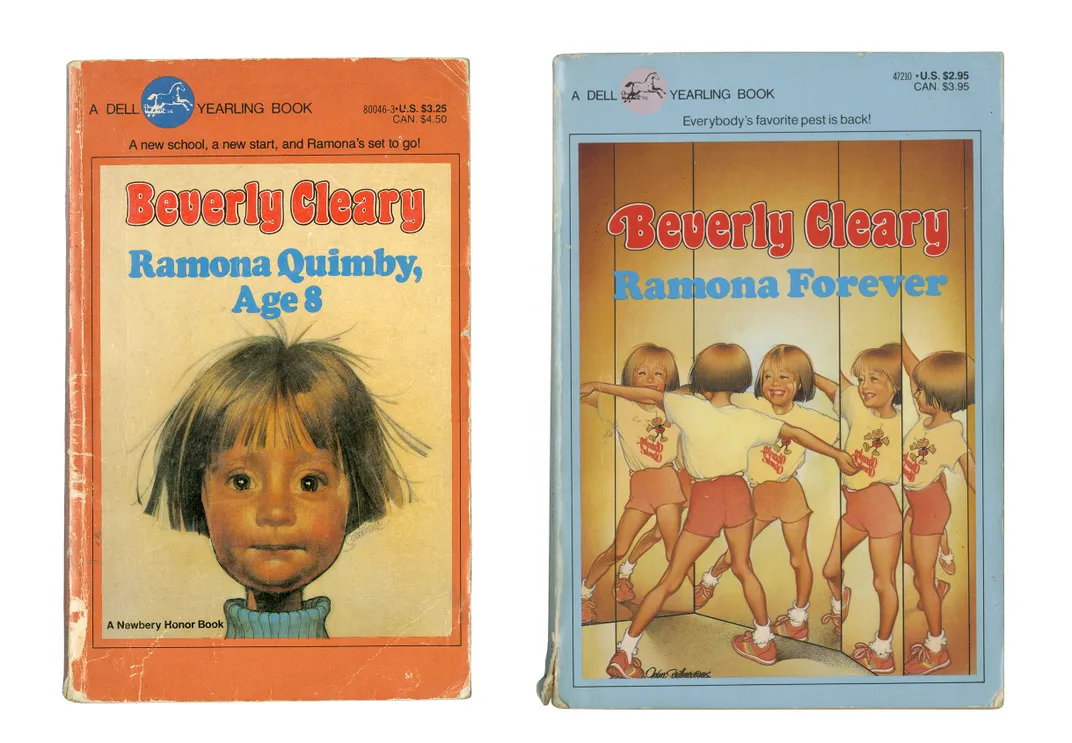

Around this same time, Joanne Scribner painted covers for the first seven books, stunning artwork that has been credited with raising the bar for children’s book covers across the board. If you belong to this generation of Ramona fans, you might remember her realistic rendering of Ramona dancing before a wall of mirrors in Ramona Forever, or a big-eyed, turtleneck-wearing Ramona on the cover of Ramona Quimby, Age 8.

The younger folk of Generation Z grew up with the shaded, more inclusive, cartoonish renderings of Tracy Dockray, who took over the job in 2006. And those being raised on the 2013 edition of the Ramona Quimby series will likely claim the illustrations by Jacqueline Rogers as the ultimate expression of the Quimbys and their world.

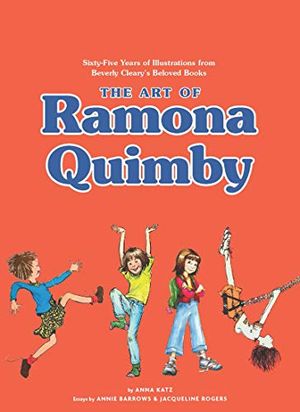

The Art of Ramona Quimby: Sixty-Five Years of Illustrations from Beverly Cleary’s Beloved Books

The Art of Ramona Quimby explores the evolution of an iconic character, and how each artist has ultimately made her timeless. For fans of illustration and design, and for those who grew up alongside Ramona, this richly nostalgic volume reminds us why we fell in love with these books.

Many Beverly Cleary fans don’t realize that the Ramona Quimby series has benefited from the efforts of more than one illustrator. Or they may have been shocked when they picked up a Ramona Quimby book to read to their own kids only to find illustrations different than those from their childhoods. When a person discovers that “their” illustrations are in fact just one set among many, a certain kind of tribalism can emerge. It’s the same kind of tribalism that has old-timers—anyone over, say, 25—complaining that they just don’t make music, movies, politicians, panty hose, or polar ice caps like they used to.

But the range of illustrations points to the fact that the Ramona stories themselves transcend generational divides. They have had such staying power because Cleary’s writing, like all good writing, makes the universal specific and the specific universal. She mostly left out details that would freeze the story within a particular time period, but you can spot evidence of zeitgeist if you are looking for it. For example, second-wave feminism was rippling across the United States during the 1960s and 1970s and just so happened to coincide with Mrs. Quimby’s choosing to work outside the home in Ramona the Brave, published in 1975. In Ramona and Her Father, published in 1977, Mr. Quimby loses his job and the family must “pinch and scrimp” to make ends meet, just like so many families did during and following the recession of the mid-1970s. It’s not just big national affairs, however, that hint at the broader context; in Ramona and Her Mother, Beezus is desperate for a haircut that looks like “that girl who ice skates on TV. You know, the one with the hair that sort of floats when she twirls around and then falls in place when she stops.” She might be referring to Dorothy Hamill who, along with her famous wedge hairstyle, won gold at the 1976 Winter Olympics.

Then again, it could all be a coincidence. Cleary never names that figure skater, or any other politician or celebrity who might tie the books down to a particular era. Girls will always have floaty-haired ice skaters to idolize. There will continue to be new social movements and recessions, mothers going to work and fathers losing their jobs, and children worrying, feeling unloved, or, if they are very, very lucky, being cared for by parents like Mr. and Mrs. Quimby.

It is the changing of the art that allows each new generation of children to see themselves and their lives represented on the pages of Cleary’s books. The changes range from the more explicit and obvious, like style of clothing—Darling’s lace-trimmed hats and day gloves, Tiegreen’s pageboys and paisley, Dockray’s and Rogers’s jeans and T-shirts—to the style of the art itself—Darling’s comic book pen-and-ink drawings, Tiegreen’s messy sketches, Scribner’s Rockwellian realism, Dockray’s cartoons, and Rogers’s clean ink drawings. My hope is that this book will show how every illustrated version of the Ramona Quimby series is beautiful and illuminating in its own way, and that the ongoing pairing of art with story has allowed the series to endure through decades of significant change in the United States and around the world.

First published in 1955, the Ramona Quimby series has maintained its relevance and relatability for 65 years and counting, because Ramona and Beezus ride childhood’s roller coaster of feelings with such humor and honesty. Their experiences are true in a way that transcends era, as are those of the adults who inhabit the Ramonaverse. Just as Ramona becomes aware of her parents and the other grown-ups as their own separate entities, with their own thoughts and feelings, we readers, as we age, can see our adult selves in the story, too. We might relate to Mr. and Mrs. Quimby’s marital bickering, their graying hair, their worry over bills, their struggles with addiction. The way they love their kids.

Twenty years have passed since the final Ramona Quimby book was published, and young readers may notice the absence of smart phones, streaming television, or other technologies ubiquitous in contemporary life. (In an interview in 2006, the ninety-five-year-old Beverly Cleary admitted that she did not know how to use the internet.) Even if the books begin to appear dated, the themes not just of childhood but also of life endure: everyday elation and insecurity, pride in artwork and hard-won callouses, the desire to be liked and seen, the hope that the people we love are happy. The joy of stomping in mud puddles and eating whipped cream.

Excerpted from The Art of Ramona Quimby: Sixty-Five Years of Illustrations from Beverly Cleary's Beloved Books, by Anna Katz, published by Chronicle Books 2020.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/c3/40c34c7f-46f2-4735-902b-de897d09bed6/art_of_ramona_quimby-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/70/54701456-2a79-4492-86e8-b5173aed685d/art_of_ramona_quimby-social.jpg)