How Should We Archive the Soundtrack to 1970s Feminism?

It’s time to talk about the lasting legacy of Olivia Records, a leading voice of the women’s music movement, whose history is ready to come out of storage

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/84/47/844704a1-4c4f-48c4-97ce-a0821f864d71/chapter5oliviacollective1973-2.jpg)

“I’m not ready to be a museum piece,” a veteran of the women’s music movement confided in me recently.

During the second wave of feminism in the United States, women’s music albums and concerts invited thousands and thousands to find validation in their identity as women and as lesbians, and to experience being the majority for a night: not in a smoke-filled, testosterone-filled bar, but in a music hall with some of the finest songwriters in the land onstage.

Though some remain downright incredulous that enough time has even passed to make their work “historical,” there’s also been an audible murmur growing in this vibrant, intelligent community of steadily graying fans: We did something important. We mattered to one another. And how we did it is a tale that matters, too.

As the historian of Olivia Records, a trailblazing all-women’s recording label that emerged from this movement, I am intimately aware that the artists and producers that were on the forefront of this distinctive cultural turning point are now approaching their 70s, as are many of their earliest fans.

With samples of now-historic album art and vinyl beginning to become objects of interest for researchers and the public-at-large, the question becomes: how should Olivia should be remembered, collected and exhibited for those unfamiliar with its legacy?

If the protest music of the 1960s turned anti-war, anti-government, pro-marijuana and even profane songs into “Top 40” radio hits, by 1973, viewpoints from the feminist journey were still nowhere to be found in the mainstream beyond the tokenism of Helen Reddy’s “I Am Woman.”

This absence, however, offered an opportunity for a “new” sound, by women, for women—including songs that didn’t candy-coat female friendships but actually acknowledged racism as well as homophobia. A collective of women seized the moment and built Olivia Records, the first national women’s music network (which has since evolved to become a lesbian lifestyle company).

These pioneers were an eclectic mix of folk performers, activists, and political theorists based in Washington, D.C.

Ginny Berson belonged to the Furies collective, a radical, separatist household that published journals, taught classes, and advocated communal living apart from men. Judy Dlugacz, 20, had postponed law school to pursue lesbian activism and was interested in finding an economically workable means of serving the women’s community. Performing as a folk musician at area clubs and coffeehouses, Meg Christian was eager to meet other women songwriters like Cris Williamson—who had released her first album in 1964 at age 16.

When Williamson came on tour to D.C., Christian and Berson not only arranged to bring other women’s music fans to the concert; in a gesture that changed history, they also scheduled a follow-up interview on Georgetown University’s “Radio Free Women” program. On the show, Berson spoke about how she and other members of the Furies collective were searching for a bigger project to invest in— “something that’s for women, by women, and supported by women’s money”—and Williamson responded with a simple yet provocative suggestion, “Why don’t you start a women’s record company?”

Over time, the excited gathering of ten settled into a collective of five women, Berson, Christian, Dlugacz, Kate Winter and Jennifer Woodul, who appear in iconic photographs as the original “Olives.” Now in its fifth decade, Olivia holds the distinction of being the first and longest-lasting woman-owned recording company in U.S. history.

Theirs isn’t just any success story. The women of Olivia were revolutionary for completely sidestepping entertainment industry paternalism. The collective took control of every aspect of record production. They taught one another how to record and mix sound, run lights, produce concerts, distribute albums and handle sales. Donations and loans came from delighted fans who first learned about Olivia artists by seeing them on tour.

It’s important to note that Olivia was building on a tradition. Black blueswomen, performing in the clubs of the Harlem Renaissance, preceded Olivia by decades in composing songs that rebuked male violence and celebrated the resonant resistance of “bulldagger” identity. White artists were just beginning to discover and learn from that songbook—and to address the racial divisions in feminist coalition-building as the ’70s dawned.

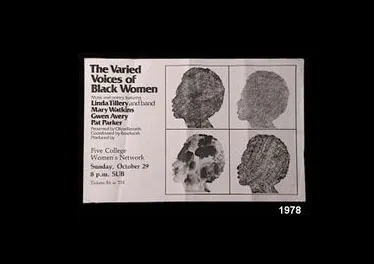

Through processing and community feedback, Olivia became an intersectional voice—beginning with the 1975 Varied Voices of Black Women tour and the 1976 release of “Where Would I Be Without You,” a spoken-word album pairing Bay Area poets Pat Parker and Judy Grahn.

From its earliest days, Olivia was singular in that it targeted gay women with one of the only positive, relationship-affirming products available to the niche group: love songs. Olivia’s first full-length record, Christian’s boldly titled 1974 LP I Know You Know, included songs like “Sweet Darling Woman” and “Ode to a Gym Teacher,” which brought the women’s music movement right into feminists’ living rooms and house parties.

Olivia’s most famous recording, Williamson’s The Changer and the Changed, appeared in 1975. Changer had developed a nearly mystical hold over its listeners by the time Ms. magazine heralded Williamson on its cover as “the new star of women’s music” in 1980. At concerts, audiences sang along to emotional ballads like “Sister” (“Lean on me, I am your sister,”) “Song of the Soul” and “Waterfall. They also sighed aloud with the yearning strains of “Sweet Woman,” which asserted “…I’ll hold you and you’ll be mine, sweet woman,” a groundbreaking lyric no other female lead vocalist was singing at the time.

Describing the mood of those early years, Dlugacz (who continues to serve as Olivia’s president) suggests “We were reaching out to an audience that wanted to be found, but not necessarily identified.” After all, at a time when LGBTQ rights and protections did not exist in U.S. law, having an Olivia album was more or less “proof” of membership in a still-illegal tribe. The ambivalence Dlugacz describes could be seen at concerts, which as defiant mass gatherings, elicited emotions from fans about having to hide integral parts of themselves. Many women wept openly at discovering community and sisterhood; at seeing the full range of others like themselves.

The concert experience was life-changing for some, and at the same time terrifying for others who longed to become involved as local producers and distributors but feared losing jobs, child custody, housing. Venues ranged from Unitarian church basements to college campuses to women-only festivals in the woods, offering fans choices between public and private settings. Self-taught producers learned to accommodate audience needs with sliding-scale ticket prices, occasional child care, and, increasingly, sign language interpretation so that deaf women, too, could experience an evening of woman-positive lyrics and political rhetoric from the stage. With the advent of affordable tape cassettes and car tapedecks, even the most closeted Olivia fans could own the music and be inspired by it while driving to and from work.

Staging concerts by and for women without men at the sound board controls proved too much for some critics, who lobbed charges of reverse discrimination, illegal exclusion of males from public events, or the inherent inferiority of female engineers (“Olivia was an all-woman company. They made a point of doing without men, even if that meant a temporary lower level of performance,” as Jerry Rodnitzky writes in Feminist Phoenix: The Rise and Fall of a Feminist Counterculture.) But most audiences were too rapt to care about imperfect sound quality, instead heady with the thrill of seeing women gain opportunity and skill in stage work roles once closed to them. And production values improved as concerts moved from fans’ living rooms and cramped clubs to better venues.

Backstage, Olivia was not without strife—throughout its history the company battled confrontations over racism and money, plus dramatic breakup drama between artist couples. A painful boycott by some former fans concerned Olivia’s employment of a transwoman, prolific sound engineer Sandy Stone, who resigned amid a bitter debate over her place in a women’s recording company. (Stone was defended, then and now, by Olivia.)

With the help of women’s dollars asserting sheer gratitude for the songbook of albums affirming women’s lives and experiences, however, Olivia continued to be propelled forward. By the fall of 1982, Olivia was already commemorating its 10-year anniversary. In late November, the collective marked the occasion with a concert by Christian and Williamson at Carnegie Hall, the first time the venue publicly hosted a lesbian majority audience for a gala event.

Olivia’s continued relevance today lies in this transparency and arc of diversity; it attracted artists who understood that music could evoke and address the range of milestones women were reaching. A single concert night could galvanize thousands to march for their rights in an era of social justice; an example of this was Olivia’s 1977 album Lesbian Concentrate, recorded in response to Anita Bryant’s homophobic “Save Our Children” campaign in Florida. Promotional materials for the album exhorted audiences to take action in securing lesbian rights.

In the 1990s, with the original collective long dispersed, and fewer women’s music venues available for still-touring artists from the collective, Olivia Records was reborn as Olivia Cruises, a lesbian lifestyle experience that has taken hundreds of thousands of women on vacations to ports around the world, rainbow flag flying snappily from the bridge of luxury ships. The cruises and resort vacations offered year-round from Olivia Travel continue on, today, and attract women of all ages, ethnicities and income levels, some celebrating their now-legal weddings and honeymoons, some rejoicing in retirement.

If it feels impossible to convey the impact of this one company in a few paragraphs, 45 years of women’s music archives sure won’t fit inside one large file box. Right now, all of Olivia’s archival material—the master recordings, the stored stock of old vinyl and cassettes, artists’ posters and press kits from touring—are currently in a back room at the travel company’s San Francisco headquarters, in the early stages of undergoing critical organization as new interest in Olivia’s legacy is reflected by museum exhibits and research requests.

Where should those Olivia albums, and veteran fans’ own scrapbooks of a lifetime in women’s music, go next—in order to educate future generations? Who will impart these stories? Where does Olivia fit on the political timeline of feminism; of grassroots American music history? Is the generation that demanded women’s history in college classes ready to see itself as historically meaningful?

A thoughtful museum staff can make the difference in welcoming, collecting, and cataloguing LGBTQ memorabilia from these potential donors. But it’s a delicate mission, all the same. As longtime outsiders, many women who have lived to see domestic partner and marriage rights become realities are still skittish about attracting too much attention, lest the heavy gavel of discrimination descend again. The new option of displaying private, quasi-underground material ephemera from a radical movement feels, to some, like coming out of the closet all over again, as well as an admission of our own mortality.

Nevertheless, academics, political archivists, musicologists, and oral historians all stand to benefit from the rich storehouse of Olivia’s legacy. (And there’s plenty to go around for those just discovering Olivia: catalogued so far is a surplus of 3,212 45 singles, 868 LP albums, 400 cassette tapes and 1,205 CDs. The music lives.)

On the 45th anniversary of Olivia’s founding, conversations about preserving both concert tour and voyage highlights have taken on a new urgency too. While all the original collective members and artists and most of the original distributors, producers and fans are still living, it’s crucial to preserve their stories now. Olivia’s material culture is secure—with many original albums still shrink-wrapped— but full oral histories and narrative memoirs are needed to pass along this torch of music activism.

We’re not only taking measure of a recording company’s success as a grassroots feminist enterprise, as a source of comfort and inspiration, as an artistic legacy with Grammy-winning and best-selling artists in the wheelhouse. We’re taking the measure of a timeline, from first daring to voice women’s lives to seeing that kind of political stance spoken at rallies, at the Academy Awards, and in exhibits marking 50 years since Stonewall. This is about women who happen to be gay being seen as part of the American fabric.

These daring women matter. Their collective history helped push forward the feminist movement, the LGBTQ movement, awareness about domestic violence and breast cancer and equal wages. The recorded ballads of their struggles and triumphs deserve to be heard and exhibited in our nation’s museums— a trumpet blast against patriarchy, and a reminder that female equality and LGBTQ rights are incomplete revolutions, still in need of anthems.

The Feminist Revolution: The Struggle for Women's Liberation

Bonnie J. Morris is the author of The Feminist Revolution an overview of women's struggle for equal rights in the late twentieth century

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.