How the Chess Set Got Its Look and Feel

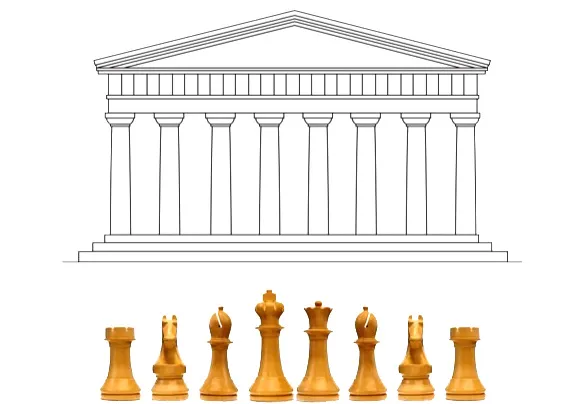

The vaunted Staunton Chess Set, the standard chess set you probably grew up with, has its roots in neoclassical architecture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Design-Chess-set-631.jpg)

Prior to 1849, there was no such thing as a “normal chess set.” At least not like we think of it today. Over the centuries that chess had been played, innumerable varieties of sets of pieces were created, with regional differences in designation and appearance. As the game proliferated throughout southern Europe in the early 11th century, the rules began to evolve, the movement of the pieces were formalized, and the pieces themselves were drastically transformed from their origins in 6th century India. Originally conceived of as a field of battle, the symbolic meaning of the game changed as it gained popularity in Europe, and the pieces became stand-ins for a royal court instead of an army. Thus, the original chessmen, known as counselor, infantry, cavalry, elephants, and chariots, became the queen, pawn, knight, bishop, and rook, respectively. By the 19th century, chess clubs and competitions began to appear all around the world, it became necessary to use a standardized set that would enable players from different cultures to compete without getting confused.

In 1849, that challenge would be met by the “Staunton” Chess Set.

The Staunton chess pieces are the ones we know and love today, the ones we simply think of as chess pieces. Prior to its invention, there were a wide variety of popular styles in England, such as The St George, The English Barleycorn, and the Northern Upright. To say nothing of the regional and cultural variations. But the Staunton quickly would surpass them all. Howard Staunton was a chess authority who organized many tournaments and clubs in London, and was widely considered to be one of the best players in the world. Despite its name, the iconic set was not designed by Howard Staunton.

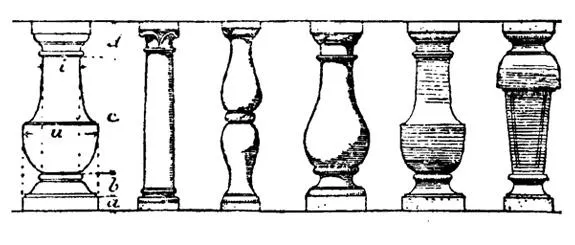

According to the most widely told origin story, the Staunton set was designed by architect Nathan Cook, who looked at a variety of popular chess sets and distilled their common traits while also, more importantly, looking at the city around him. Victorian London’s Neoclassical architecture had been influenced by a renewed interest in the ruins of ancient Greece and Rome, which captured the popular imagination after the rediscovery of Pompeii in the 18th century. The work of architects like Christopher Wren, William Chambers, John Soane, and many others inspired the column-like, tripartite division of king, queen, and bishop. A row of Staunton pawns evokes Italianate balustrades enclosing of stairways and balconies.

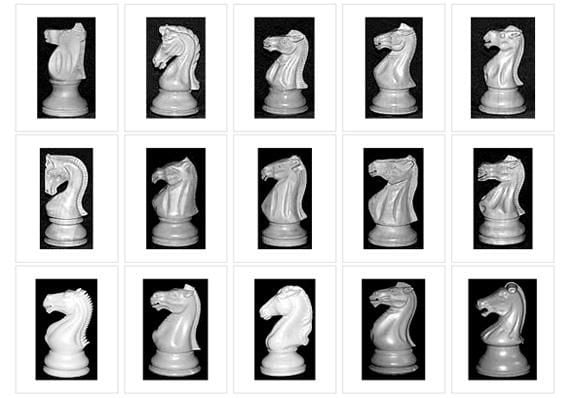

And the knight, the most intricate and distinct piece of any chess set, is unique in that it’s the only piece that is not an abstracted representation of a designation; it’s a realistically carved horse head. The Staunton Knight was likely inspired by a sculpture on the east pediment of the Parthenon depicting horses drawing the chariot of Selene, the Moon Goddess. Selene’s horse is part of a collection of sculptures controversially removed from the Parthenon by Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, during his tenure as ambassador to the Ottoman court. Known as the “Elgin Marbles,” these sculptures were donated to the British Museum in 1816 and were enormously popular with a British public that was growing increasingly interested in classical antiquities. According to the British Museum, Selene’s horse “is perhaps the most famous and best loved of all the sculptures of the Parthenon. It captures the very essence of the stress felt by a beast that has spent the night drawing the chariot of the Moon across the sky….the horse pins back its ears, the jaw gapes, the nostrils flare, the eyes bulge, veins stand out and the flesh seems spare and taut over the flat plate of the cheek bone.” Now you know why the knights in your chess sets always look like they’re screaming in agony.

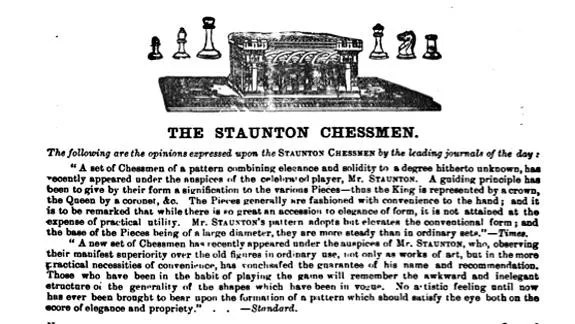

Staunton appreciated the simplicity and legibility of Cook’s design, and allowed Cook to use of his name in marketing the new pieces, which were first offered to the public in 1849 by purveyors John Jaques of London. On the same day the new pieces hit shelves across London, an advertisement in the Illustrated London News celebrated the new set as “the Staunton Chessmen”:

“A set of Chessmen, of a pattern combining elegance and solidity to a degree hitherto unknown, has recently appeared under the auspices of the celebrated player Mr. Staunton….The pieces generally are fashioned with convenience to the hand; and it is to be remarked, that while there is so great an accession to elegance of form, it is not attained at the expense of practical utility. Mr. Staunton’s pattern adopts but elevates the conventional form; and the base of the Pieces being of a large diameter, they are more steady than ordinary sets.”

Now, there’s some confusion about the design of the first Staunton set because Nathaniel Cook also happened to be the brother-in law of John Jaques, as well as the editor of of the News– a paper that counted Staunton among its contributors. The three men were definitely in cahoots, and some speculate that Cook was not actually the designer but was merely an agent acting on behalf of Jaques, who was looking to increase his profits by creating a cheaper, more efficient design that appealed to a variety of players and had the blessing of the most famous chess player in London. Though the design is sometimes incorrectly attributed to Mr. Staunton, he provided only the initial endorsement and functioned as a sort of spokesman, passionately advocating the set in public. The design was a huge success. The simple, largely unadorned forms of the Staunton set made it relatively cheap and easy to produce, and instantly comprehensible. Since the 1920s, the Staunton set has been required by worldwide chess organizations.

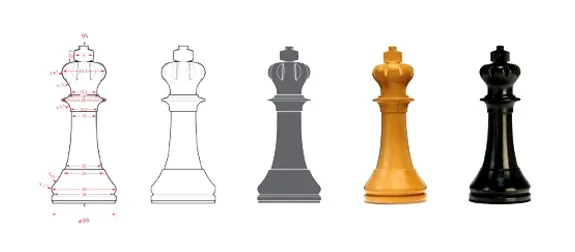

From that original set advertised in the pages of the Illustrated London News, hundreds of different versions of the have emerged. While some variation is tolerated, there are several key distinguishing characteristics that define a set as a Staunton: the king is topped with a cross and, as the the tallest piece, serves as a metric for the height of the others; the queen is topped by a crown and ball; the bishop has a split top; the knight is a horse head; the rook is a squat castle turret.”

Recently, the Staunton set got a makeover. The new piece designs are part of an earlier project by noted design conultancy Pentagram, the rebranding of World Chess, an organization that aims to bring chess back to a level of popularity it enjoyed during the heyday of Bobby Fischer. Other than coming up with a new brand and identity for chess, Pentagram also designed a new tv-friendly competitive playing environment and an interactive website that lets fans follow games live online via “chesscasting”.

Daniel Weil, partner of Pentagram, reinterpreted the classic Staunton set for the 2013 World Chess Candidates Tournament in London. Weil says that to begin the project he had to “unravel the rationale behind the original set.” This meant looking back to the pieces’ origins in Neoclassical architecture. Following the lead of Cook (or Jaques), Weil also looked to the Parthenon. As part of his subtle redesign, Weil resized the set so that when the eight primary pieces are lined up at the beginning of play, their angle reflects the pitch of the Pantheon’s pediment. Weil also streamlined the pieces somewhat, returning a precision and thoughtfulness to the Staunton set that, in his view, had been lost in many of the Staunton variations created over the last 160 years. The design also reflects the relative value of each piece according to tournament rules; the more a piece is worth, the wider the base. The new Staunton pieces were also designed to accommodate different styles of play, such as the grips that Weil ostentatiously refers to as the “north hold” and the more theatrical “south hold”. The high-quality set debuted in tournament play this year and is now also available to the public. Weill told Design Week, “When chess started to become popular in the 19th century it became a social showcase, so everyone had a set on show. I wanted to make an object of quality so that people could also show it off.”

Inspired by the Neoclassical architecture of Victorian London and a very modern need for standardization and mass production, the Staunton chessmen helped popularize the game and quickly became the world standard. The new Staunton pieces by Daniel Weil reinforces this architectural history of the original pieces while respecting their timeless design.

Sources:

The House of Staunton; “Daniel Weil redesigns the chess set,” Design Week; “The History of the Staunton Chessmen” and “The Staunton Legacy,” Staunton Chess Sets; “The Staunton Chess Pattern,” ChessUSA; Henry A. Davidson, A Short History of Chess (Random House Digital, 2010); Pentagram

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)